History of India

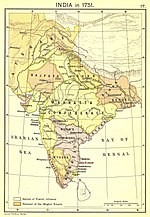

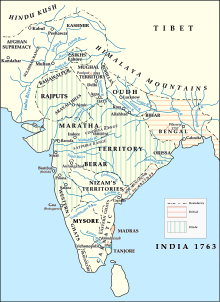

[14][15] The early modern period began in the 16th century, when the Mughal Empire conquered most of the Indian subcontinent,[16] signaling the proto-industrialisation, becoming the biggest global economy and manufacturing power.

[17][18][19] The Mughals suffered a gradual decline in the early 18th century, largely due to the rising power of the Marathas, who took control of extensive regions of the Indian subcontinent, and numerous Afghan invasions.

[31] According to Michael D. Petraglia and Bridget Allchin: Y-Chromosome and Mt-DNA data support the colonisation of South Asia by modern humans originating in Africa.

Michael Fisher adds:[40] The earliest discovered instance ... of well-established, settled agricultural society is at Mehrgarh in the hills between the Bolan Pass and the Indus plain (today in Pakistan) (see Map 3.1).

[73] Two key figures of the Kuru state were king Parikshit and his successor Janamejaya, who transformed this realm into the dominant political, social, and cultural power of northern India.

[73] The archaeological PGW (Painted Grey Ware) culture, which flourished in north-eastern India's Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh regions from about 1100 to 600 BCE,[61] is believed to correspond to the Kuru and Panchala kingdoms.

[77] The Central Ganges Plain, where Magadha gained prominence, forming the base of the Maurya Empire, was a distinct cultural area,[78] with new states arising after 500 BCE.

[91] Ancient Buddhist texts, like the Aṅguttara Nikāya,[92] make frequent reference to these sixteen great kingdoms and republics—Anga, Assaka, Avanti, Chedi, Gandhara, Kashi, Kamboja, Kosala, Kuru, Magadha, Malla, Matsya (or Machcha), Panchala, Surasena, Vṛji, and Vatsa.

Especially focused in the Central Ganges plain but also spreading across vast areas of the northern and central Indian subcontinent, this culture is characterised by the emergence of large cities with massive fortifications, significant population growth, increased social stratification, wide-ranging trade networks, construction of public architecture and water channels, specialised craft industries, a system of weights, punch-marked coins, and the introduction of writing in the form of Brahmi and Kharosthi scripts.

[109] Under Chandragupta Maurya and his successors, internal and external trade, agriculture, and economic activities all thrived and expanded across India thanks to the creation of a single efficient system of finance, administration, and security.

However, after the death of Agnimitra, the empire rapidly disintegrated;[130] inscriptions and coins indicate that much of northern and central India consisted of small kingdoms and city-states that were independent of any Shunga hegemony.

[168] At the peak, his Empire covered much of North and Northwestern India, extended East until Kamarupa, and South until Narmada River; and eventually made Kannauj (in present Uttar Pradesh) his capital, and ruled until 647 CE.

[169] His biography Harshacharita ("Deeds of Harsha") written by Sanskrit poet Banabhatta, describes his association with Thanesar and the palace with a two-storied Dhavalagriha (White Mansion).

[175] Lack of appeal among the rural masses, who instead embraced Brahmanical Hinduism formed in the Hindu synthesis, and dwindling financial support from trading communities and royal elites, were major factors in the decline of Buddhism.

[221] This was an important period in the development of fine arts in Southern India, especially in literature as the Western Chalukya kings encouraged writers in the native language of Kannada, and Sanskrit like the philosopher and statesman Basava and the great mathematician Bhāskara II.

Soldiers from that region and learned men and administrators fleeing Mongol invasions of Iran migrated into the subcontinent, thereby creating a syncretic Indo-Islamic culture in the north.

[239] In the first two decades after the founding of the empire, Harihara I gained control over most of the area south of the Tungabhadra river and earned the title of Purvapaschima Samudradhishavara ("master of the eastern and western seas").

By 1374 Bukka Raya I, successor to Harihara I, had defeated the chiefdom of Arcot, the Reddys of Kondavidu, and the Sultan of Madurai and had gained control over Goa in the west and the Tungabhadra-Krishna doab in the north.

[249] The kings used titles such as Gobrahamana Pratipalanacharya (literally, "protector of cows and Brahmins") and Hindurayasuratrana (lit, "upholder of Hindu faith") that testified to their intention of protecting Hinduism and yet were at the same time staunchly Islamicate in their court ceremonials and dress.

[250] The empire's founders, Harihara I and Bukka Raya I, were devout Shaivas (worshippers of Shiva), but made grants to the Vaishnava order of Sringeri with Vidyaranya as their patron saint, and designated Varaha (an avatar of Vishnu) as their emblem.

[259] The empire's patronage enabled fine arts and literature to reach new heights in Kannada, Telugu, Tamil, and Sanskrit, while Carnatic music evolved into its current form.

[265][266][267] The Reddy dynasty successfully defeated the Delhi Sultanate and extended their rule from Cuttack in the north to Kanchi in the south, eventually being absorbed into the expanding Vijayanagara Empire.

This period witnessed the further development of Indo-Islamic architecture;[296][297] the growth of Marathas and Sikhs enabled them to rule significant regions of India in the waning days of the Mughal empire.

[citation needed] The second form of asserting power involved treaties in which Indian rulers acknowledged the company's hegemony in return for limited internal autonomy.

The rebel soldiers were later joined by Indian nobility, many of whom had lost titles and domains under the Doctrine of Lapse and felt that the company had interfered with a traditional system of inheritance.

The Crown controlled the company's lands directly and had considerable indirect influence over the rest of India, which consisted of the Princely states ruled by local royal families.

Historian Nitish Sengupta describes the renaissance as having started with reformer and humanitarian Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1775–1833), and ended with Asia's first Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941).

The means of achieving the proposed measure were later enshrined in the Government of India Act 1919, which introduced the principle of a dual mode of administration, or diarchy, in which elected Indian legislators and appointed British officials shared power.

[400] In 1919, Colonel Reginald Dyer ordered his troops to fire their weapons on peaceful protestors, including unarmed women and children, resulting in the Jallianwala Bagh massacre; which led to the Non-cooperation Movement of 1920–1922.

[407][408][409] Also, this period saw one of the largest mass migrations anywhere in modern history, with a total of 12 million Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims moving between the newly created nations of India and Pakistan (which gained independence on 15 and 14 August 1947 respectively).