Antonio Gramsci

[4] Gramsci drew insights from varying sources — not only other Marxists but also thinkers such as Niccolò Machiavelli, Vilfredo Pareto, Georges Sorel, and Benedetto Croce.

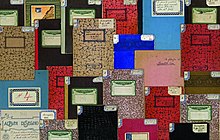

The notebooks cover a wide range of topics, including the history of Italy and Italian nationalism, the French Revolution, fascism, Taylorism and Fordism, civil society, the state, historical materialism, folklore, religion, and high and popular culture.

[9][10][11] The Albanian origin of his father's family is attested in the surname Gramsci, an Italianised form of Gramshi, which stems from the definite noun of the placename Gramsh, a small town in central-eastern Albania.

[13] Francesco Gramsci worked as a low-level official,[7] and his financial difficulties and troubles with the police forced the family to move about through several villages in Sardinia until they finally settled in Ghilarza.

Gramsci started secondary school in Santu Lussurgiu and completed it in Cagliari,[18] where he lodged with his elder brother Gennaro, a former soldier whose time on the mainland had made him a militant socialist.

[20][21][22] They perceived their neglect as a result of privileges enjoyed by the rapidly industrialising Northern Italy, and they tended to turn to a growing Sardinian nationalism, brutally repressed by troops from the Italian mainland,[23] as a response.

At university, he had come into contact with the thought of Antonio Labriola, Rodolfo Mondolfo, Giovanni Gentile, and most importantly, Benedetto Croce, possibly the most widely respected Italian intellectual of his day.

From 1914 onward, Gramsci's writings for socialist newspapers such as Il Grido del Popolo (The Cry of the People [it]) earned him a reputation as a notable journalist.

Vladimir Lenin saw the L'Ordine Nuovo group as closest in orientation to the Bolsheviks, and it received his backing against the anti-parliamentary programme of a left communist, Amadeo Bordiga.

[31] In the course of tactical debates within the party, Gramsci's group mainly stood out due to its advocacy of workers' councils, which had come into existence in Turin spontaneously during the large strikes of 1919 and 1920.

For Gramsci, these councils were the proper means of enabling workers to take control of the task of organising production, and saw them as preparing "the whole class for the aims of conquest and government".

[32] Although he believed his position at this time to be in keeping with Lenin's policy of "All Power to the Soviets",[33] his stance that these Italian councils were communist rather than just one organ of political struggle against the bourgeoisie, was attacked by Bordiga for betraying a syndicalist tendency influenced by the thought of Georges Sorel and Daniel De Leon.

Such a front would ideally have had the PCd'I at its centre, through which Moscow would have controlled all the leftist forces, but others disputed this potential supremacy, as socialists had a significant, while communists seemed relatively young and too radical.

In late 1922 and early 1923, Benito Mussolini's government embarked on a campaign of repression against the opposition parties, arresting most of the PCd'I leadership, including Bordiga.

In 1926, Joseph Stalin's manoeuvres inside the Bolshevik party moved Gramsci to write a letter to the Comintern in which he deplored the opposition led by Leon Trotsky but also underlined some presumed faults of the leader.

[38] On 9 November 1926, the Fascist government enacted a new wave of emergency laws, taking as a pretext an alleged attempt on Mussolini's life that had occurred several days earlier.

Over this period, "his teeth fell out, his digestive system collapsed so that he could not eat solid food ... he had convulsions when he vomited blood and suffered headaches so violent that he beat his head against the walls of his cell.

He was due for release on 21 April 1937 and planned to retire to Sardinia for convalescence, but a combination of arteriosclerosis, pulmonary tuberculosis, high blood pressure, angina, gout, and acute gastric disorders meant that he was too ill to move.

[49] Such organic intellectuals do not simply describe social life in accordance with scientific rules but instead articulate, through the language of culture, the feelings and experiences which the masses could not express for themselves.

To Gramsci, it was the duty of organic intellectuals to speak to the obscured precepts of folk wisdom, or common sense (senso comune), of their respective political spheres.

Gramsci posits that movements such as reformism and fascism, as well as the scientific management and assembly line methods of Frederick Winslow Taylor and Henry Ford respectively, are examples of this.

Drawing from Niccolò Machiavelli, Gramsci argues that the modern Prince — the revolutionary party — is the force that will allow the working class to develop organic intellectuals and an alternative hegemony within civil society.

Nonetheless, willpower cannot achieve anything it likes in any given situation: when the consciousness of the working class reaches the stage of development necessary for action, it will encounter historical circumstances that cannot be arbitrarily altered.

By virtue of his belief that human history and collective praxis determine whether any philosophical question is meaningful or not, Gramsci's views run contrary to the metaphysical materialism and copy theory of perception advanced by Friedrich Engels,[58][59] and Lenin,[60] although he does not explicitly state this.

[65] Nonetheless, it was necessary to effectively challenge the ideologies of the educated classes and to do so Marxists must present their philosophy in a more sophisticated guise and attempt to genuinely understand their opponents' views.

They find the Gramscian approach to philosophical analysis, reflected in current academic controversies, to conflict with open-ended, liberal inquiry grounded in apolitical readings of the classics of Western culture.

[67][68] His theory of hegemony has drawn criticism from those who believe that the promotion of state intervention in cultural affairs risks undermining the free exchange of ideas, which is essential for a truly open society.

[72] The historian Jean-Yves Frétigné argues that Gramsci and the socialists more generally were naïve in their assessment of the fascists and as a result underestimated the brutality of which the regime was capable.

Even though those letters later turned out to be false, the article remains part of the Gramscian bibliography and triggered numerous reactions, including from Giampiero Boniperti, who on behalf of the club the following day told at La Stampa: "We are pleased to know that among our fans there have been personalities who have marked an era from the political, economic, and intellectual point of view.

Fifteen years later, he pointed at the degeneration of stadium cheering, which emerged with the advent of fascism and the consequent nationalisation of the sport that he said extinguished political and trade union commitment.