Grande Armée

Widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest fighting forces ever assembled, it suffered catastophic losses during the disastrous Peninsular War followed by the invasion of Russia in 1812, after which it never recovered its strategic superiority and ended in total defeat for Napoleonic France by the Peace of Paris in 1815.

The Grande Armée was formed in 1804 from L'Armée des côtes de l'Océan (The Army of the Ocean Coasts), a force of over 100,000 men that Napoleon had assembled for the proposed invasion of Britain.

While most contingents were commanded by French generals, except for the Polish and Austrian corps, soldiers could climb the ranks regardless of class, wealth, or national origin, unlike many of the other European armies at the time.

When the Austrian and Russian armies began their preparations to invade France in late 1805, the Grande Armée was quickly ordered across the Rhine into southern Germany, leading to Napoleon's victories at Ulm and Austerlitz.

The Grande Armée was originally formed as L'Armée des côtes de l'Océan (Army of the Ocean Coasts) intended for the invasion of Britain, at the port of Boulogne in 1804.

Affairs were decisively settled on 2 December 1805 at the Battle of Austerlitz, where the numerically inferior Grande Armée routed a combined Russo-Austrian army led by Russian Emperor Alexander I.

The campaign resumed in the spring and this time General Levin August von Bennigsen's Russian army was soundly defeated at the Battle of Friedland on 14 June 1807.

On 24 June 1812, shortly before the invasion, the assembled troops with a total strength of 685,000 men were made up of:[12] • 410,000 from the French Empire (present-day France, Italy, the Low Countries, and several German states) • 95,000 Poles • 35,000 Austrians • 30,000 Italians[13] • 24,000 Bavarians • 20,000 Saxons • 20,000 Prussians • 17,000 Westphalians • 15,000 Swiss • 10,000 Danes and Norwegians[14][15] • 4,000 Spaniards• 4,000 Portuguese • 3,500 Croats • 2,000 Irish The new Grande Armée was somewhat different from before; over one-third of its ranks were now filled by non-French conscripts coming from satellite states or countries allied to France.

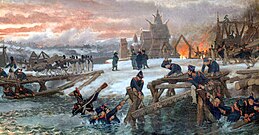

The behemoth force crossed the Niemen River on 24 June 1812, and Napoleon hoped that quick marching could place his men between the two main Russian armies, commanded by Generals Barclay de Tolly and Pyotr Bagration.

But due to the poor quality of French troops and cavalry following the Russian campaign, along with miscalculations by certain subordinate marshals, these triumphs were not decisive enough to win the war and only secured an armistice.

Napoleon hoped to use this respite to increase the quantity and improve the quality of the Grande Armée, but when Austria joined the Allies, his strategic situation grew bleak.

However, the adoption of the Trachenberg Plan by the Allies, which called for avoiding direct conflict with Napoleon and focusing on his subordinates, paid dividends as the French suffered defeats at Großbeeren, the Katzbach, Kulm, and Dennewitz.

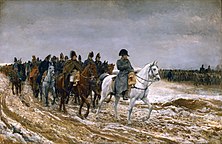

In the Six Days' Campaign of February 1814, the 30,000-man Grande Armée inflicted 20,000 casualties on Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher's scattered corps at a cost of just 2,000 for themselves.

Marshal Emmanuel de Grouchy's delayed advance against the Prussians allowed Blücher to rally his men after Ligny and march on to Wellington's aid at the Battle of Waterloo, which resulted in the final, decisive defeat for Napoleon.

[24] The Army General Headquarters included the office of the Major-Général's (Chief of Staff's) Cabinet with their four departments: Movements, Secretariat, Accounting and Intelligence (orders of battle).

Since the emperor was his own "operations officer", it can be said that Berthier's job consisted of absorbing Napoleon's strategic intentions, translating them into written orders and transmitting them with the utmost speed and clarity.

[27] Napoleon placed great trust in his corps commanders and usually allowed them a wide freedom of action, provided they acted within the outlines of his strategic objectives and worked together to accomplish them.

Although the infantry was rarely committed en masse, the Guard's cavalry was often thrown into battle as the killing blow and its artillery used to pound enemies prior to assaults.

Their name comes from their original mission; Voltigeurs were to vault upon horses of friendly cavalry for faster movement, an idea which proved impractical if not outright impossible.

Nicknamed Hell's Picadors or Los Diablos Polacos (The Polish Devils) by the Spanish, these medium and light horse (Chevau-Légers Lanciers) cavalry had near equal speed to the hussars, shock power almost as great as the cuirassiers, and were nearly as versatile as the dragoons.

Superb gun-crew training allowed Napoleon to move the weapons at great speed to either bolster a weakening defensive position, or else hammer a potential break in enemy lines.

Besides superior training, Napoleon's artillery was also greatly aided by the numerous technical improvements to French cannons by General Jean Baptiste de Gribeauval which made them lighter, faster, and much easier to sight, as well as strengthened the carriages and introduced standard sized calibres.

When it arrived over the target, the fuse, if correctly prepared, exploded the main charge, breaking open the metal outer casing and forcing flying fragments in all directions.

[52] Prior to this, the French, like all other period armies, had employed contracted, civilian teamsters who would sometimes abandon the guns under fire, rendering them immobile, rather than risk their lives or their valuable teams of horses.

This name, which is still used today, was both a play on the word (jeu de mot) and a reference to their seemingly magical abilities to grant wishes and make things appear much like the mythical Genie.

The logistical system was also aided by a technological innovation in the form of the food preservation technique invented by Nicolas Appert, which led to modern canning methods.

During the Napoleonic Wars, every French regiment, division, and corps had its own medical staff, consisting of ambulance units, orderlies to perform nursing duties, apothecaries, surgeons, and doctors.

[citation needed] But the real advance for conveying long-range dispatches came in the form of an ingenious optical telegraph Semaphore system invented by Claude Chappe.

Some of the widely used and effective formations and tactics included: Maréchal d'Empire, or Marshal of the Empire, was not a rank within the Grande Armée, but a personal title granted to distinguished divisional generals, along with higher pay and privileges.

According to Alain Pigeard,[59] between 1792 and 1814 no fewer than 190 foreign-born soldiers, that is, around 6 per cent of the French Army's senior officers, were promoted to general, including Józef Poniatowski, who was appointed Marshal of the Empire during the Battle of Leipzig (1813), only to die less than 48 hours later.