Piano

The piano is widely employed in classical, jazz, traditional and popular music for solo and ensemble performances, accompaniment, and for composing, songwriting and rehearsals.

Despite its weight and cost, the piano's versatility, the extensive training of musicians, and its availability in venues, schools, and rehearsal spaces have made it a familiar instrument in the Western world.

Invented in 1700, the fortepiano was the second keyboard instrument (in addition to the clavichord which predates it) to allow gradations of volume and tone according to how forcefully or softly the player presses or strikes the keys, unlike the pipe organ and harpsichord.

[5] The invention of the piano is credited to Bartolomeo Cristofori of Padua, Italy, who was employed by Ferdinando de' Medici, Grand Prince of Tuscany, as the Keeper of the Instruments.

Cristofori's new instrument remained relatively unknown until an Italian writer, Scipione Maffei, wrote an enthusiastic article about it in 1711, including a diagram of the mechanism, that was translated into German and widely distributed.

John Broadwood joined with another Scot, Robert Stodart, and a Dutchman, Americus Backers, to design a piano in the harpsichord case—the origin of the "grand".

In 1821, Sébastien Érard invented the double escapement action, which incorporated a repetition lever (also called the balancier) that permitted repeating a note even if the key had not return to its resting position.

Felt, which Jean-Henri Pape was the first to use in pianos in 1826, was a more consistent material, permitting wider dynamic ranges as hammer weights and string tension increased.

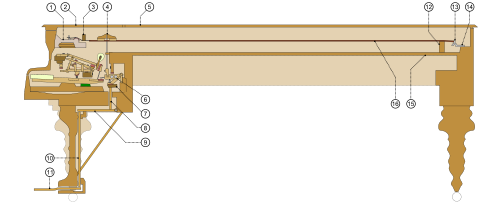

[20] The sostenuto pedal (see below), invented in 1844 by Jean-Louis Boisselot and copied by the Steinway firm in 1874,[21] allowed for a wider range of effects.One innovation that helped create the powerful sound of the modern piano was the use of a massive, strong, cast iron frame.

[22] Also called the "plate", the iron frame sits atop the soundboard, and serves as the primary bulwark against the force of string tension that can exceed 20 tons (180 kilonewtons) in total for a modern grand piano.

[28] The use of a Capo d’Astro bar instead of agraffes in the uppermost treble allowed the hammers to strike the strings in their optimal position, greatly increasing that area's power.

Eager to copy these effects, Theodore Steinway invented duplex scaling, which used short lengths of non-speaking wire bridged by the "aliquot" throughout much of the upper range of the piano, always in locations that caused them to vibrate sympathetically in conformity with their respective overtones—typically in doubled octaves and twelfths.

This design is attributed to Christian Ernst Friderici (a pupil of Gottfried Silbermann) in Germany and Johannes Zumpe in England,[32] and it was improved by changes first introduced by Guillaume-Lebrecht Petzold in France and Alpheus Babcock in the United States.

Their overwhelming popularity was the result of inexpensive construction and price, although their tone and performance were limited by narrow soundboards, simple actions and string spacing that made proper hammer alignment difficult.

Modern equivalents of the player piano include the Bösendorfer CEUS, Yamaha Disklavier and QRS Pianomation,[38] using solenoids and MIDI rather than pneumatics and rolls.

The scores for music for prepared piano specify the modifications, for example, instructing the pianist to insert pieces of rubber, paper, metal screws, or washers in between the strings.

Additional samples emulate sympathetic resonance of the strings when the sustain pedal is depressed, key release, the drop of the dampers, and simulations of techniques such as re-pedalling.

This is especially true of the outer rim, which is most commonly made of hardwood, typically hard maple or beech, and its massiveness serves as an essentially immobile object from which the flexible soundboard can best vibrate.

According to Harold A. Conklin,[47] the purpose of a sturdy rim is so that, "... the vibrational energy will stay as much as possible in the soundboard instead of dissipating uselessly in the case parts, which are inefficient radiators of sound."

[49][full citation needed] A modern exception, Bösendorfer (an Austrian manufacturer of high-quality pianos) constructs their inner rims from solid spruce,[50] the same wood that the soundboard is made from, which is notched to allow it to bend; rather than isolating the rim from vibration, their "resonance case principle" allows the framework to resonate more freely with the soundboard, creating additional coloration and complexity of the overall sound.

The bass strings of a piano are made of a steel core wrapped with one or two layers of copper wire, to increase their mass whilst retaining flexibility.

[55] The numerous parts of a piano action are generally made from hardwood, such as maple, beech, or hornbeam; however, since World War II, makers have also incorporated plastics.

The Mandolin pedal used a similar approach, lowering a set of felt strips with metal rings in between the hammers and the strings (aka rinky-tink effect).

This extended the life of the hammers when the Orch pedal was used, a good idea for practicing, and created an echo-like sound that mimicked playing in an orchestral hall.

While some folk and blues pianists were self-taught, in classical and jazz, there are well-established piano teaching systems and institutions, including pre-college graded examinations, university, college and music conservatory diplomas and degrees, ranging from the B.Mus.

Changes in musical styles and audience preferences over the 19th and 20th century, as well as the emergence of virtuoso performers, contributed to this evolution and to the growth of distinct approaches or schools of piano playing.

[70][71][72][73] Well-known approaches to piano technique include those by Dorothy Taubman, Edna Golandsky, Fred Karpoff, Charles-Louis Hanon and Otto Ortmann.

During the 19th century, American musicians playing for working-class audiences in small pubs and bars, particularly African-American composers, developed new musical genres based on the modern piano.

Introduced to Burma during the mid-19th century, the piano was quickly indigenized by court musicians and uses a novel "technique of interlocked fingering with both hands extending a single melodic line allowed for agogic embellishment, fleeting grace notes in syncopated spirals around a steady underlying beat found in the bell and clapper time keepers", adapted to play Mahāgīta compositions.

A large number of composers and songwriters are proficient pianists because the piano keyboard offers an effective means of experimenting with complex melodic and harmonic interplay of chords and trying out multiple, independent melody lines that are played at the same time.