Gravitational wave background

[1] The signal may be intrinsically random, like from stochastic processes in the early Universe, or may be produced by an incoherent superposition of a large number of weak independent unresolved gravitational-wave sources, like supermassive black-hole binaries.

Some examples of these primordial sources include time-varying inflationary scalar fields in the early universe, "preheating" mechanisms after inflation involving energy transfer from inflaton particles to regular matter, cosmological phase transitions in the early universe (such as the electroweak phase transition), cosmic strings, etc.

With existing telescopes, many years of observation are needed to detect a signal, and detector sensitivity improves gradually.

[10] On 11 February 2016, the LIGO and Virgo collaborations announced the first direct detection and observation of gravitational waves, which took place in September 2015.

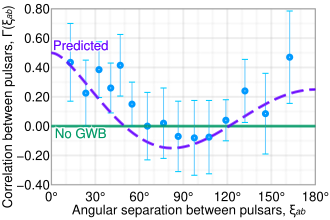

[13][14] On 28 June 2023, the North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves collaboration announced evidence for a GWB using observational data from an array of millisecond pulsars.

[15][16] Observations from EPTA,[17] Parkes Observatory[18] and Chinese Pulsar Timing Array (CPTA)[19][20] were also published on the same day, providing cross validation of the evidence for the GWB using different telescopes and analysis methods.

[22][23] The sources of this gravitational-wave background can not be identified without further observations and analyses, although binaries of supermassive black holes are leading candidates.