Big Bang nucleosynthesis

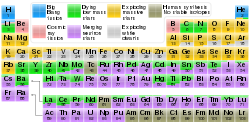

Elements heavier than lithium are thought to have been created later in the life of the Universe by stellar nucleosynthesis, through the formation, evolution and death of stars.

The Big Bang nucleosynthesis (BBN) model assumes a homogeneous plasma, at a temperature corresponding to 1 MeV, consisting of electrons annihilating with positrons to produce photons.

The BBN model follows the nuclear reactions of these baryons as the temperature and pressure drops due to expansion of the universe.

Thus the model first determines the ratio of neutrons to protons and uses this as an input to calculate the hydrogen, deuterium, tritium, and 3He.

[2]: 315 As the temperature and density continue to fall, reactions involving combinations of protons and neutrons shift towards heavier nuclei.

Due to the higher binding energy of He, the free neutrons and the deuterium nuclei are largely consumed, leaving mostly protons and helium.

This parameter corresponds to the baryon density and controls the rate at which nucleons collide and react; from this it is possible to calculate element abundances after nucleosynthesis ends.

Although the baryon per photon ratio is important in determining element abundances, the precise value makes little difference to the overall picture.

Without major changes to the Big Bang theory itself, BBN will result in mass abundances of about 75% of hydrogen-1, about 25% helium-4, about 0.01% of deuterium and helium-3, trace amounts (on the order of 10−10) of lithium, and negligible heavier elements.

[3]: 69 [2]: 313 The history of Big Bang nucleosynthesis began a proposal[4][5] in the 1940s by George Gamow that nuclear reactions during a hot initial phase of the universe produced the observed hydrogen and helium.

Calculations by his student Ralph Alpher were published[6] in the famous Alpher–Bethe–Gamow paper outlined a theory of light-element production in the early universe.

The first detailed calculations of the primordial isotopic abundances came in 1966[7][8] and have been refined over the years using updated estimates of the input nuclear reaction rates.

[9]: 3 The first systematic Monte Carlo study of how nuclear reaction rate uncertainties impact isotope predictions, over the relevant temperature range, was carried out in 1993.

As the temperature dropped, the equilibrium shifted in favour of protons due to their slightly lower mass, and the n/p ratio smoothly decreased.

Almost all neutrons that fused instead of decaying ended up combined into helium-4, due to the fact that helium-4 has the highest binding energy per nucleon among light elements.

[11] The baryon–photon ratio, η, is the key parameter determining the abundances of light elements after nucleosynthesis ends.

(An important feature is that there are no stable nuclei with mass 5 or 8, which implies that reactions adding one baryon to 4He, or fusing two 4He, do not occur).

Another feature is that the process of nucleosynthesis is determined by conditions at the start of this phase of the life of the universe, and proceeds independently of what happened before.

However, very shortly thereafter, around twenty minutes after the Big Bang, the temperature and density became too low for any significant fusion to occur.

At this point, the elemental abundances were nearly fixed, and the only changes were the result of the radioactive decay of the two major unstable products of BBN, tritium and beryllium-7.

[13] Big Bang nucleosynthesis produced very few nuclei of elements heavier than lithium due to a bottleneck: the absence of a stable nucleus with 8 or 5 nucleons.

However, this process is very slow and requires much higher densities, taking tens of thousands of years to convert a significant amount of helium to carbon in stars, and therefore it made a negligible contribution in the minutes following the Big Bang.

The predicted abundance of CNO isotopes produced in Big Bang nucleosynthesis is expected to be on the order of 10−15 that of H, making them essentially undetectable and negligible.

[15] Big Bang nucleosynthesis predicts a primordial abundance of about 25% helium-4 by mass, irrespective of the initial conditions of the universe.

The temperatures, time, and densities were sufficient to combine a substantial fraction of the deuterium nuclei to form helium-4 but insufficient to carry the process further using helium-4 in the next fusion step.

[citation needed] This explanation is also consistent with calculations that show that a universe made mostly of protons and neutrons would be far more clumpy than is observed.

Specifically, the theory yields precise quantitative predictions for the mixture of these elements, that is, the primordial abundances at the end of the big-bang.

As noted above, in the standard picture of BBN, all of the light element abundances depend on the amount of ordinary matter (baryons) relative to radiation (photons).

These pieces of additional physics include relaxing or removing the assumption of homogeneity, or inserting new particles such as massive neutrinos.

One can insert a hypothetical particle (such as a massive neutrino) and see what has to happen before BBN predicts abundances that are very different from observations.