Gravitational-wave astronomy

In 1978, Russell Alan Hulse and Joseph Hooton Taylor Jr. provided the first experimental evidence for the existence of gravitational waves by observing two neutron stars orbiting each other and won the 1993 Nobel Prize in physics for their work.

In 2015, nearly a century after Einstein's forecast, the first direct observation of gravitational waves as a signal from the merger of two black holes confirmed the existence of these elusive phenomena and opened a new era in astronomy.

Subsequent detections have included binary black hole mergers, neutron star collisions, and other violent cosmic events.

LIGO co-founders Barry C. Barish, Kip S. Thorne, and Rainer Weiss were awarded the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics for their ground-breaking contributions in gravitational wave astronomy.

Challenges that remain in the field include noise interference, the lack of ultra-sensitive instruments, and the detection of low-frequency waves.

The 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics was subsequently awarded to Rainer Weiss, Kip Thorne and Barry Barish for their role in the direct detection of gravitational waves.

[5][6] The LIGO detectors observed gravitational waves from the merger of two stellar-mass black holes, matching predictions of general relativity.

[10] This finding has been characterized as revolutionary to science, because of the verification of our ability to use gravitational-wave astronomy to progress in our search and exploration of dark matter and the big bang.

[11] In June 2023, four PTA collaborations, the three mentioned above and the Chinese Pulsar Timing Array, delivered independent but similar evidence for a stochastic background of nanohertz gravitational waves.

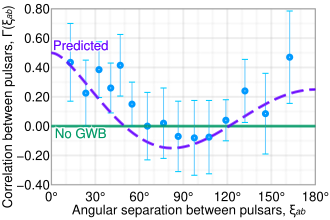

[14] Each provided an independent first measurement of the theoretical Hellings-Downs curve, i.e., the quadrupolar correlation between two pulsars as a function of their angular separation in the sky, which is a telltale sign of the gravitational wave origin of the observed background.

Originating with the visible band, as technology advanced, it became possible to observe other parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, from radio to gamma rays.

Russell Hulse and Joseph Taylor were awarded the 1993 Nobel Prize in Physics for showing that the orbital decay of a pair of neutron stars, one of them a pulsar, fits general relativity's predictions of gravitational radiation.

[25] In 2017, the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Rainer Weiss, Kip Thorne and Barry Barish for their role in the first detection of gravitational waves.

Gravitational waves can be emitted by many systems, but, to produce detectable signals, the source must consist of extremely massive objects moving at a significant fraction of the speed of light.

It is also possible to see further back in time than with electromagnetic radiation, as the early universe was opaque to light prior to recombination, but transparent to gravitational waves.

Cosmic inflation, a hypothesized period when the universe rapidly expanded during the first 10−36 seconds after the Big Bang, would have given rise to gravitational waves; that would have left a characteristic imprint in the polarization of the CMB radiation.

[52] Space-based detectors like LISA should detect objects such as binaries consisting of two white dwarfs, and AM CVn stars (a white dwarf accreting matter from its binary partner, a low-mass helium star), and also observe the mergers of supermassive black holes and the inspiral of smaller objects (between one and a thousand solar masses) into such black holes.

LISA should also be able to listen to the same kind of sources from the early universe as ground-based detectors, but at even lower frequencies and with greatly increased sensitivity.

[57] While still at an early stage, a technique similar to the triangulation used by cell phones to determine their location in relation to GPS satellites, will help astronomers tracking down the origin of the waves.