Great Divergence

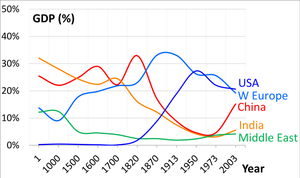

[2] Scholars have proposed a wide variety of theories to explain why the Great Divergence happened, including geography, culture, intelligence, institutions, colonialism, resources, and pure chance.

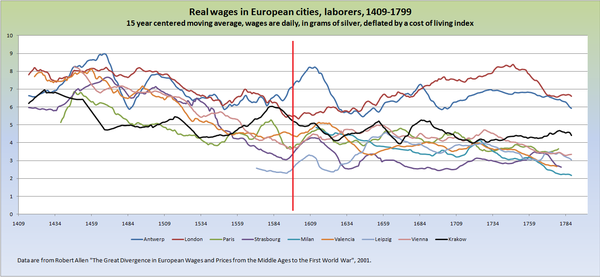

[19][20][21] Economic Historian Prasannan Parthasarathi argued that wages in parts of South India, particularly Mysore, could be on par with Britain, but evidence is scattered and more research is needed to draw any conclusion.

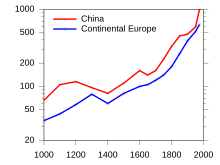

Although core regions in Eurasia had achieved a relatively high standard of living by the 18th century, shortages of land, soil degradation, deforestation, lack of dependable energy sources, and other ecological constraints limited growth in per capita incomes.

After the Viking, Muslim, and Magyar invasions waned in the 10th century, Western Christian Europe entered a period of prosperity, population growth and territorial expansion known as the High Middle Ages.

Prior to that, economic growth rates in northwestern Europe were neither sustained nor remarkable, and income per capita was similar to "peak levels achieved hundreds of years earlier in the most developed regions of Italy and China.

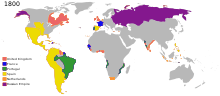

"[37] The West had a series of unique advantages compared to Asia, such as the proximity of coal mines; the discovery of the New World, which alleviated ecological restraints on economic growth (land shortages etc.

The result was a dramatic shift in the center of population and industry from the home of Chinese civilization around the Yellow River to the south of the country, a trend only partially reversed by the re-population of the north from the 15th century.

[44] Chinese goods such as silk, tea, and ceramics were in great demand in Europe, leading to an inflow of silver, expanding the money supply and facilitating the growth of competitive and stable markets.

[66] After the death of Muhammad Ali in 1849, his industrialization programs fell into decline, after which, according to historian Zachary Lockman, "Egypt was well on its way to full integration into a European-dominated world market as supplier of a single raw material, cotton."

[71] According to University of Michigan political scientist Mark Dincecco, "the high land/ labor ratio may have made it less likely that historical institutional centralization at the "national level" would occur in sub-Saharan Africa, thwarting further state development.

[23] Jared Diamond and Peter Watson argue that a notable feature of Europe's geography was that it encouraged political balkanization, such as having several large peninsulas[82] and natural barriers such as mountains and straits that provided defensible borders.

[84] In his book Guns, Germs, and Steel, Diamond argues that advanced cultures outside Europe had developed in areas whose geography was conducive to large, monolithic, isolated empires.

[87] The historian Niall Ferguson attributes this divergence to the West's development of six "killer apps", which he finds were largely missing elsewhere in the world in 1500 – "competition, the scientific method, the rule of law, modern medicine, consumerism and the work ethic".

When fragmentation afforded merchants multiple politically independent routes on which to ship their goods, European rulers refrained from imposing onerous regulations and levying arbitrary tolls, lest they lose mercantile traffic to competing realms.

[92] This helped the spread of ideas, as did the east–west axis of the Mediterranean which lined up with the prevailing winds and its many archipelagos which together aided navigation, as was also done by the great rivers which brought inland access, all of which further increased immigration.

[93] Testing theories related to geographic endowments economists William Easterly and Ross Levine find evidence that tropics, germs, and crops affect development through institutions.

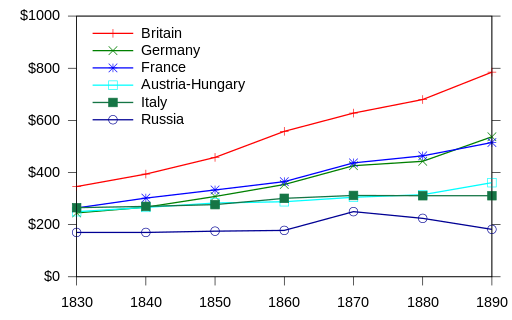

[32] Beginning in the early 19th century, economic prosperity rose greatly in the West due to improvements in technological efficiency,[95] as evidenced by the advent of new conveniences including the railroad, steamboat, steam engine, and the use of coal as a fuel source.

[99] Economic historian Paul Bairoch presents a contrary argument, that Western countries such as the United States, Britain and Spain did not initially have free trade, but had protectionist policies in the early 19th century, as did China and Japan.

[117] However, responding to the work of Bairoch, Pomeranz, Parthasarathi and others, more subsequent research has found that parts of 18th century Western Europe did have higher wages and levels of per capita income than in much of India, Ottoman Turkey, Japan and China.

[127] Robert Allen argues that the relatively high wages in eighteenth century Britain both encouraged the adoption of labour-saving technology and worker training and education, leading to industrialisation.

Following political pressure from the new industrial manufacturers, in 1813, Parliament abolished the two-centuries-old, protectionist East India Company monopoly on trade with Asia and introduced import tariffs on Indian textiles.

[153] The introduction of railways into India have been a source of controversy regarding their overall impact, but evidence points to a number of positive outcomes such as higher incomes, economic integration, and famine relief.

[158] A 2001 paper by Daren Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson found that nations with temperate climates and low levels of mortality were more popular with settlers and were subjected to greater degrees of colonial rule.

Chen (2012) similarly claims that cultural differences were the most fundamental cause for the divergence, arguing that the humanism of the Renaissance followed by the Enlightenment (including revolutionary changes in attitude towards religion) enabled a mercantile, innovative, individualistic, and capitalistic spirit.

[22] Yasheng Huang argued that the imperial examination system monopolized the most capable intellectuals in service of the state, sustained the propagation of Confucianism, and preempted the emergence of ideas that could challenge it.

[167] Historians like Yu Yingshi and Billy So have shown that as Chinese society became increasingly commercialized from the Song dynasty onward, Confucianism had gradually begun to accept and even support business and trade as legitimate and viable professions, as long as merchants stayed away from unethical actions.

The Indian economy was characterized by vassal-lord relationships, which weakened the motive of financial profit and the development of markets; a talented artisan or merchant could not hope to gain much personal reward.

[173] Other similar arguments proposed include the gradual prohibition of independent religious judgements (Ijtihad) and a strong communalism which limited contacts with outside groups and the development of institutions dealing with more temporary interactions of various kinds, according to Kuran.

Countries such as Prussia, Bohemia and Poland had very little freedom in comparison to the West;[vague] forced labor left much of Eastern Europe with little time to work towards proto-industrialization and ample manpower to generate raw materials.

[194] A 2017 study in the Quarterly Journal of Economics argued, "medieval European institutions such as guilds, and specific features such as journeymanship, can explain the rise of Europe relative to regions that relied on the transmission of knowledge within closed kinship systems (extended families or clans)".