Great Hanoi Rat Massacre

As they felt that they were making insufficient progress, and due to labour strikes, they created a bounty programme that paid a reward of 1¢ for each rat killed.

[7] Furthermore, the city of Hanoi also possessed a citadel and fort, these were ironically constructed in 1803 (the year after the Nguyễn dynasty was established by the Gia Long Emperor) with the assistance of French military engineers that were trained in the Vauban tradition of fortification.

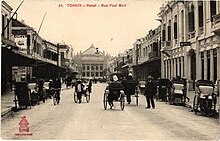

Large parts of Hanoi were cleared to make room for the new French-style inner city that was filled with broad tree-lined boulevards, colonial-style villas, and well-tended gardens.

[10] This new area would be known as the "French Quarter" (Quartier Européen / Khu phố Pháp, today's Ba Đình District), as some visitors would describe it as "a slice of Paris on the other side of the world".

[12] These actions were enacted to make Hanoi a showcase for France's civilising mission in Indochina and to provide the city with the very first electricity network in Asia.

[12] By the time of Paul Doumer's departure in March 1902, over 19 kilometers of sewers had been built underneath Hanoi,[13] the largest concentration of which lay beneath the "French Quarter".

[10][12] In the sewers rats found no natural predators and if they would get hungry they could easily penetrate directly into the most luxurious apartments in the city through the "highway" hidden deep beneath human footsteps.

[10][12] Just a few years earlier in 1894 the famous Alexandre Yersin discovered the Yersinia pestis bacteria that caused the disease and his colleague Paul-Louis Simond linked it to fleas found on rodents.

Expanding cities and long-distance trade networks offered rats new habitats and new ways to travel distances far greater than they could with just their stubby little legs.

It is impossible to know the exact rat population, but scientific estimates indicate that these rodents currently outnumber human beings by several billion.

[6] Before the Bubonic plague hit the American city of San Francisco[21] its municipal authorities decided to enact a quarantine policy for its Chinatown.

[6] The realisation that these might be plague-carrying cats created a panic among health officials leading to their response to attempt to eradicate the rat infestation before the city would succumb to the pandemic.

[6] Many of these technocrats were drawn by French colonial empire, where they could engage in widespread social experiments without the fear of opposition or negative public opinion as they could use the military to enforce their policies.

[25] Yersin as well as a number of other medical experts in Hanoi were concerned about the bubonic plague arriving there from southern China on the newly established steamship lines.

[10] "One had to enter the dark and cramped sewer system, make one’s way through human waste in various forms of decay, and hunt down a relatively fierce wild animal which could be carrying fleas with the bubonic plague or other contagious diseases.

This is not even to mention the probable existence of numerous other dangerous animals, such as snakes, spiders, and other creatures, that make this author’s skin crawl with anxiety."

[24] The VNEconomics Academy of Blockchain and Cryptocurrencies reports that Professor Nguyễn Văn Tuấn claimed that by 1904, the authorities increased the commission for every rat killed to 4 cents.

[6] All data collected by the French such as the city's population figures, the number of plague cases to the daily count of dead rats were just best guesses.

[2] As the French authorities found that the extermination process wasn't going fast enough they proceeded to Plan B, offering any enterprising local the opportunity to get in on the hunt for rats.

[24] Among the reasons why the death toll was higher among the Vietnamese was because they kept their sick family members a secret out of a fear that if the authorities found out about them that they would come to check and interfere.

[24] This reflected the racial politics of the time, as similar attitudes existed in places like South Africa,[28] India,[29] the United States,[30] and Hong Kong.

[6] Buried deep within the overseas archives Vann found a folder that labelled "Destruction of Hazardous Animals: Rats" concerning pest control.

[6] The archives included about a hundred of identical forms that would list the number of rats that were reportedly killed between April 1902 and July 1902 in the first and second arrondissements (districts) of Hanoi.

[10][13] While researching the archives, he attempted to reach into the top drawer of a card catalogue that was dedicated to pre-1954 French-language files, and then suddenly felt the sensation of a rat walking over his hand.

[6] The producers of Freakonomics Radio asked Vann if he would attend the podcast to illustrate the economic principle of perverse incentives, a concept he was unfamiliar with at the time.

[6] In 2018 Micheal G. Vann and comic book artist Liz Clarke published the book The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt: Empire, Disease, and Modernity in French Colonial Vietnam (Vietnamese: Cuộc đại thảm sát chuột tại Hà Nội: Đế chế, Dịch bệnh và Sự Hiện đại ở VN thời Pháp thuộc) through the Oxford University Press.

[6] In an interview with PV Thanh Niên Vann said "This book is like a love letter I want to send to Hanoi" (Cuốn sách này cũng giống như bức thư tình tôi muốn gửi tới Hà Nội) talking about the hospitality that he received when he visited the city back in 1997.

[13] Ivan Franceschini of the Made in China Journal describes the work as being a praiseworthy case study in the history of imperialism, noting that the book delves deep into the racialised economic inequalities of empire.

[6] Franceschini further notes that it explores the idea of colonisation as a form of modernisation, while also discussing the creation of a radical power differential between "the West and the rest" created by industrial capitalism.

[6] Furthermore, Michael G. Vann felt that the topics discussed in the book would be presented in a better way if they were in an illustrated format as he wanted to visually showcase the differences between the Vietnamese and French neighbourhoods of Hanoi.