Great Hippocampus Question

The dispute between Thomas Henry Huxley and Richard Owen became central to the scientific debate on human evolution that followed Charles Darwin's publication of On the Origin of Species.

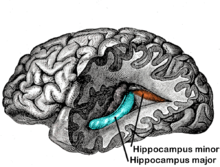

The key point that Owen asserted was that only humans had part of the brain then known as the hippocampus minor (now called the calcar avis), and that this gave us our unique abilities.

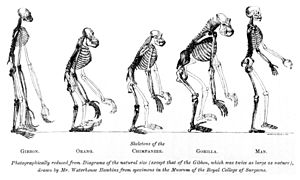

Owen's brilliance and political skills made him a leading figure in the scientific establishment, developing ideas of divine archetypes produced by vague secondary laws similar to a form of theistic evolution, while emphasising the differences separating man from ape.

[1][2] At the end of 1844 the anonymous book Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation brought wide public interest in transmutation of species and the idea that humans were descended from apes, and after a slow initial response, strong condemnation from the scientific establishment.

When Thomas Henry Huxley savagely reviewed the latest edition of Vestiges in 1854, Darwin wrote to him, making friends while cautiously admitting to being "almost as unorthodox about species".

[13][14] Huxley was among the friends rallying round the publication of Darwin's On the Origin of Species, and was sharpening his "beak and claws" to disembowel "the curs who will bark and yelp".

[15][16] Charles Kingsley was sent a review copy, and told Darwin that he had "long since, from watching the crossing of domesticated animals and plants, learnt to disbelieve the dogma of the permanence of species.

[19] Owen bitterly attacked Huxley, Hooker and Darwin, but also signalled acceptance of a kind of evolution as a teleological plan in a continuous "ordained becoming", with new species appearing by natural birth.

After Charles Daubeny's paper "On the Final Causes of the Sexuality of Plants with Particular Reference to Mr. Darwin's Work", the chairman asked Huxley for comments, but he declined as he thought the public venue inappropriate.

In response, Huxley flatly but politely "denied altogether that the difference between the brain of the gorilla and man was so great" in a "direct and unqualified contradiction" of Owen, citing previous studies as well as promising to provide detailed support for his position.

[24] From February to May Huxley delivered a very popular series of sixpenny lectures for working men at the School of Mines where he taught, on "The Relation of Man to the Rest of the Animal Kingdom".

Owen arranged for him to speak and display his collections on stage at a spectacular Royal Geographical Society meeting on 25 February, and followed this by giving a lecture at the Royal Institution on 19 March on the brains of The Gorilla and the Negro, asserting that the dispute was one of interpretation rather than fact,[26] and hedging his previous claim by stating that humans alone had a hippocampus minor "as defined in human anatomy".

Punch featured the issue several times that year, notably on 18 May 1861 when a cartoon under the heading Monkeyana showed a standing gorilla with a sign parodying Josiah Wedgwood's anti-slavery slogan "Am I Not A Man And A Brother?".

", and noting:[33][34] It then recounts Huxley's ripostes, and: The poem was actually by the eminent palaeontologist Sir Philip Egerton who, as a trustee of the Royal College of Surgeons and the British Museum, acted as Owen's patron.

"[33] In the second issue of Huxley's Natural History Review, an article by George Rolleston on the orangutan brain showed the features that Owen claimed apes lacked, and when Owen responded in a letter to the Annals and Magazine of Natural History that the issue was a matter of definition rather than fact, Huxley made a public dissection of a spider monkey that had died at the zoo, to support his case.

A detailed paper by William Henry Flower in the prestigious journal, the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, reviewed the earlier literature and presented his own studies based on having dissected sixteen species of primates, including prosimians, monkeys and an orangutan.

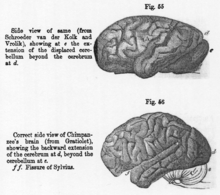

The Dutch anatomists Jacobus Schroeder van der Kolk and Willem Vrolik found that Owen had repeatedly used their 1849 illustration of a chimpanzee's brain to support his arguments, and to prevent the public from being misled they dissected the brain of an orangutan that had died in the Amsterdam zoo, reporting at a meeting of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences that the three features Owen claimed were unique to humans were present in this ape.

They admitted that their earlier illustration was incorrect due to the way they had removed the brain for inspection, and suggested that Owen had become "lost" and "fell into a trap" in debating against Darwin.

This was the first British Association annual meeting attended by Charles Kingsley, and during the meeting he produced a privately printed satirical skit on the argument, "a little squib for circulation among his friends" written in the style of the then popular stage character Lord Dundreary, a good natured but brainless aristocrat known for huge bushy sideburns and for mangling proverbs or sayings in "Dundrearyisms".

The London Quarterly Review took up the joke, describing the confrontation of Owen with Huxley and his supporters Rolleston and Flower dramatically: "Animation increased, 'decorous reticence' was at an end, and all parties enjoyed the scene except the disputants.

[37] At about the same time as he was attending the Cambridge British Association meeting in 1862, instalments of Charles Kingsley's story for children The Water-Babies, A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby were being published in Macmillan's Magazine as a serial.

Kingsley incorporated material modified from his skit about Dundreary's speech On the Great Hippocampus Question, as well as other references to the protagonists, the British Association, and notable scientists of the day.

That is contrary to nature,” you must wait a little, and see; for perhaps even they may be wrong.Keeping up an even-handed treatment, Kingsley introduced as a character in the story Professor Ptthmllnsprts (Put-them-all-in-spirits) as an amalgam of Owen and Huxley, satirising each in turn.

You may think that there are other more important differences between you and an ape, such as being able to speak, and make machines, and know right from wrong, and say your prayers, and other little matters of that kind; but that is a child’s fancy, my dear.

His intention was expressed in a letter to Charles Lyell which referred to the Monkeyana poem of 1861: "I do not think you will find room to complain of any want of distinctness in my definition of Owen's position touching the Hippocampus question.

[42] Sir Charles Lyell's authoritative Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man was also published in 1863, and included a detailed review of the hippocampus question which gave solid and unambiguous support to Huxley's arguments.

In an attempt to refute Lyell's judgement, Owen again defended his classification scheme, introducing a new claim that the hippocampus minor was virtually absent in an "idiot".

In a long footnote, Owen cited himself and the earlier literature to admit at last that in apes "all the homologous parts of the human cerebral organ exist".

[48] Even many of his supporters, including Charles Lyell and Alfred Russel Wallace, thought that though humans shared a common ancestor with apes, the higher mental faculties could not have evolved through a purely material process.

[49] In a talk about biological systematics (classification) and cladistics given at the American Museum of Natural History in 1981, the paleontologist Colin Patterson discussed an argument put in a paper by Ernst Mayr that humans could be distinguished from apes by the presence of Broca's area in the brain.