Alfred Russel Wallace

[4] He independently conceived the theory of evolution through natural selection; his 1858 paper on the subject was published that year alongside extracts from Charles Darwin's earlier writings on the topic.

By the end of 1845, Wallace was convinced by Robert Chambers's anonymously published treatise on progressive development, Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, but he found Bates was more critical.

"[26] After reading A Voyage up the River Amazon by William Henry Edwards, Wallace and Bates estimated that by collecting and selling natural history specimens such as birds and insects they could meet their costs, with the prospect of good profits.

[28][29] Wallace spent four years charting the Rio Negro, collecting specimens and making notes on the peoples and languages he encountered as well as the geography, flora, and fauna.

Wallace hired a Malay named Ali as a general servant and cook, and spent the early 1855 wet season in a small Dyak house at the foot of Mount Santubong, overlooking a branch outlet of the Sarawak River.

[48] In March he moved to the Simunjon coal-works, operated by the Borneo Company under Ludvig Verner Helms, and supplemented collecting by paying workers a cent for each insect.

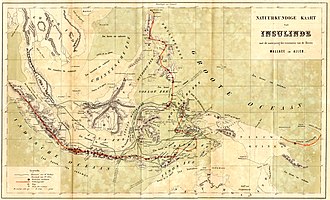

"[55] In the same letter, Wallace said birds from Bali and Lombok, divided by a narrow strait, "belong to two quite distinct zoological provinces, of which they form the extreme limits", Java, Borneo, Sumatra and Malacca, and Australia and the Moluccas.

"[74] Wallace opposed eugenics, an idea supported by other prominent 19th-century evolutionary thinkers, on the grounds that contemporary society was too corrupt and unjust to allow any reasonable determination of who was fit or unfit.

[75] In his 1890 article "Human Selection" he wrote, "Those who succeed in the race for wealth are by no means the best or the most intelligent ..."[76] He said, "The world does not want the eugenicist to set it straight," "Give the people good conditions, improve their environment, and all will tend towards the highest type.

The first part of the book covered the major scientific and technical advances of the century; the second part covered what Wallace considered to be its social failures including the destruction and waste of wars and arms races, the rise of the urban poor and the dangerous conditions in which they lived and worked, a harsh criminal justice system that failed to reform criminals, abuses in a mental health system based on privately owned sanatoriums, the environmental damage caused by capitalism, and the evils of European colonialism.

The New York Times called him "the last of the giants [belonging] to that wonderful group of intellectuals composed of Darwin, Huxley, Spencer, Lyell, Owen, and other scientists, whose daring investigations revolutionized and evolutionized the thought of the century".

[97] Wallace wrote to Henry Bates in 1845 describing it as "an ingenious hypothesis strongly supported by some striking facts and analogies, but which remains to be proven by ... more research".

[115] The reaction to the reading was muted, with the president of the Linnean Society remarking in May 1859 that the year had not been marked by any striking discoveries;[116] but, with Darwin's publication of On the Origin of Species later in 1859, its significance became apparent.

This rebutted a paper by a professor of geology at the University of Dublin that had sharply criticised Darwin's comments in the Origin on how hexagonal honey bee cells could have evolved through natural selection.

[131] They point to a largely overlooked passage of Wallace's famous 1858 paper, in which he likened "this principle ... [to] the centrifugal governor of the steam engine, which checks and corrects any irregularities".

Wallace responded that he and Bates had observed that many of the most spectacular butterflies had a peculiar odour and taste, and that he had been told by John Jenner Weir that birds would not eat a certain kind of common white moth because they found it unpalatable.

In his 1878 book Tropical Nature and Other Essays, he wrote extensively about the coloration of animals and plants, and proposed alternative explanations for a number of cases Darwin had attributed to sexual selection.

Furthermore, under such conditions, natural selection would favour the development of barriers to hybridisation, as individuals that avoided hybrid matings would tend to have more fit offspring, and thus contribute to the reproductive isolation of the two incipient species.

Wallace's anthropological observations of Native Americans in the Amazon, and especially his time living among the Dayak people of Borneo, had convinced him that human beings were a single species with a common ancestor.

[147] In 1864, in the aforementioned paper, he stated "It is the same great law of the preservation of favored races in the struggle for life, which leads to the inevitable extinction of all those low and mentally undeveloped populations with which Europeans come in contact.

[153][154] Wallace's belief that human consciousness could not be entirely a product of purely material causes was shared by a number of prominent intellectuals in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

[157] Much later in his life Wallace returned to these themes, that evolution suggested that the universe might have a purpose, and that certain aspects of living organisms might not be explainable in terms of purely materialistic processes.

One historian of science has pointed out that, through both private correspondence and published works, Darwin and Wallace exchanged knowledge and stimulated each other's ideas and theories over an extended period.

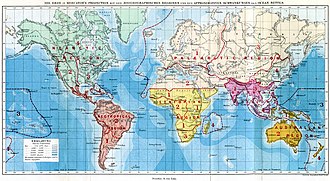

[164] In 1872, at the urging of many of his friends, including Darwin, Philip Sclater, and Alfred Newton, Wallace began research for a general review of the geographic distribution of animals.

Such islands were characterised by a complete lack of terrestrial mammals and amphibians, and their inhabitants (except migratory birds and species introduced by humans) were typically the result of accidental colonisation and subsequent evolution.

The island's forests were further damaged by the "reckless waste"[174] of the East India Company from 1651, which used the bark of valuable redwood and ebony trees for tanning, leaving the wood to rot unused.

[195] In 1870, a flat-Earth proponent named John Hampden offered a £500 wager (roughly equivalent to £60,000 in 2023[196]) in a magazine advertisement to anyone who could demonstrate a convex curvature in a body of water such as a river, canal, or lake.

The commission found that smallpox vaccination was effective and should remain compulsory, though they recommended some changes in procedures to improve safety, and that the penalties for people who refused to comply be made less severe.

[159] Reasons for this lack of attention may have included his modesty, his willingness to champion unpopular causes without regard for his own reputation, and the discomfort of much of the scientific community with some of his unconventional ideas.

[225][226] The Alfred Russel Wallace building is a prominent feature of the Glyntaff campus at the University of South Wales, by Pontypridd, with several teaching spaces and laboratories for science courses.