Great Mongol Shahnameh

[2] It is the largest early book in the tradition of the Persian miniature,[3] in which it is "the most magnificent manuscript of the fourteenth century",[4] "supremely ambitious, almost awe-inspiring",[5] and "has received almost universal acclaim for the emotional intensity, eclectic style, artistic mastery and grandeur of its illustrations".

[6] It was produced in the context of the Il-khanid court ruling Persia (modern day Iran) as part of the Mongol Empire, about a century after their conquest, and just as the dynasty was about to collapse.

It remained in Persia until the early 20th century, when it was broken up in Europe by the dealer George Demotte, and now exists as 57 individual pages, many significantly tampered with, in a number of collections around the world.

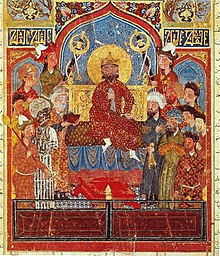

[11] Themes given emphasis by the choices of what to illustrate include "the enthronement of minor kings, dynastic legitimacy, and the role of women as kingmakers", as well as scenes of murder and mourning.

[12] These choices are usually taken as reflecting contemporary political events,[13] including "tensions between the Il-khanid dynasty and Persian subjects",[14] and the Black Death, which was ravaging Persia in these years.

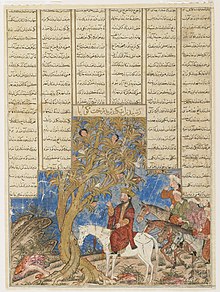

[15] Borrowings from Chinese art, in the shape of gnarled trees, round-topped wave-like rocks and tightly curling strips of cloud, dominate the landscapes and skies.

It covers the pre-Islamic history of Persia, beginning in pure legend, but by the final Sassanid kings giving a reasonable accurate historical account, mixed in with romantic stories.

It represented an assertion of Persian national identity,[21] begun during the Iranian Intermezzo after the Arab Abbasid Caliphate had lost effective control of Persia.

It is clear from literary references that there was a pre-Islamic tradition of illustrating stories later included in the Shahnameh in wall-paintings and probably other media,[24] and some Islamic ceramics may well show such scenes.

[27] The books had a political purpose, which is reflected in the choice of incidents to illustrate: "in such works, the hitherto stubbornly alien rulers of Iran were expressing a new and public commitment to the religion and cultural heritage of the very lands that they themselves had devastated some two generations previously—and doing so with an urgency that suggested they were making up for lost time.

[30] After Rašīd-al-Dīn was executed in 1318 the workshop declined or ceased, but his son Ḡīāṯ-al-Dīn Moḥammad revived it when he rose in the court in the 1330s, and the Great Mongol Shahnameh is assumed to have been created there.

Pages were pulled apart to give two sides with miniatures, and to disguise this and the resulting damage, calligraphers were hired to add new text, often from the wrong part of the work, as Demotte did not expect his new clientele of wealthy collectors to be able to read Persian.

[45] Scholars have been very critical of the "infamous" Demotte,[46] and it irked many that the manuscript he treated so brutally carried his name, so the new name of "Great Mongol Shahnameh" was promoted, and has generally won acceptance.