Persian mythology

Historically, these were regions long ruled by dynasties of various Iranian empires,[note 1][1][2][3] that incorporated considerable aspects of Persian culture through extensive contact with them,[note 2] or where sufficient Iranian peoples settled to still maintain communities who patronize their respective cultures.

The resultant discord mirrors the nationalistic ideals of the early Islamic era as well as the moral and ethical perceptions of the Zoroastrian period, in which the world was perceived to be locked in a battle between the destructive Ahriman and his hordes of demonic Divs and their Aneran supporters, versus the Creator Ahura Mazda, who although not participating in the day-to-day affairs of mankind, was represented in the world by the izads and the righteous ahlav Iranians.

The purpose of the sacrifice for the evil gods was to pay them a ransom to stop killing people.

On the other side of the fence is Zahhak, a symbol of despotism who was, finally, defeated by Kāve, who led a popular uprising against him.

Before the Medes, Aryan civilizations lived in this land, which mostly had no linguistic, racial, or even religious kinship with their neighbors outside the Iranian plateau, and sometimes they had solidarity.

These tribes, who controlled the southern half of Iran, the west and the northwest, had their own special myths.

The mythology of the Elamites, who were a separate people and had linguistic affinities with the non-Aryans of India, shares some myths contained in the Rigveda.

The close languages of these two groups also confirm their common roots; Therefore, the origin of the mythology of these two nations has been the same in the distant past, but the migration of Indians from the Aryan plateau to lands with different nature and climatic conditions, as well as indigenous peoples, has brought about fundamental changes in their mythology and religious beliefs.

Fire is sacred and praised in Iranian and Indian beliefs, and they used to perform sacrifices for the gods in a similar manner.

The final compilation of most of them is in the early Islamic era; But most of them are based on the texts of the late Sasanian period.

The dynamism arose, the mountains were created, the rivers flowed, and the moon and stars began to rotate.

These evil forces, which are considered to be the assistants of Angra Mainyu (Ahriman), are mentioned by the names of Div and Druq.

Ahura Mazda and Ahriman have been at war with each other since eternity, and life in the world is a reflection of the cosmic struggle of the two.

Although he is mentioned in the Shahnameh of the Mardosh kingdom, in the Avesta he is a three-headed, six-eyed and three-nosed demon with a body full of scorpions.

The first three thousand years begins with the birth of two children named Ahura Maza and Ahriman from Zarvan.

Ahura Maza first creates Amesha Spenta, which are: Sepand Mino, Khordad, Mordad, Bahman, Ordibehesht, Shahrivar and Spandarmad.

After the pact is concluded, Ahura Mazda utters the true prayer, Ahunur, and as a result, Ahriman falls to hell and remains unconscious there for the second three thousand years.

At the end of the second three thousand years, Ahriman, with the help of his allies, returns and decides to destroy the current world.

The third three thousand years: in this period, we see the conflict of Ahriman and his demons with Ahura Maza and his gods.

However, all these are mythological characters in the Avesta, and in the Zoroastrian texts of the Sasanian period, they are gods of the Izder race.

In this period, Zoroastrian religion is presented and we see fundamental changes in the mythological history of Iran.

However, it is clear that the last Kiyan king who is defeated by Alexander in mythological texts is the same Darius III of Achaemenid.

A fusion of mythological history and real history: This period corresponds to the time when the Iranian mythological narrative coincides with concrete historical data such as stone inscriptions and Greek texts; It means the fall of Iran at the hands of Alexander.

The final data of the Parthian era in Iranian mythology deals with the battle between Artabanus IV and Ardeshir I, which is the same as what was found in Latin and Armenian texts.

He rides the legendary stallion Rakhsh and wears a special suit named Babr-e Bayan in battles.

In the eastern regions of Greater Iran, and by the Zoroastrians of the Indian subcontinent it is rendered as Jamshed Bahram, is an Iranian hero in Shahnameh.

The existence of these small kingdoms and the feudalistic background point to a date in the Parthian period of Iranian history.

Contrary to the mentioned cases, the deeds of mythological characters were transferred to modern Persian in the form of epics and preserved to a large extent.

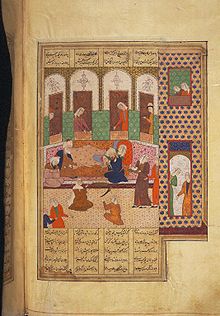

As the greatest epic work of Iranian history, Ferdowsi's Shahnameh was written in the Islamic era.

Some Iranians even tried to establish a kind of equivalent relationship between the mythological figures of these two completely different frameworks.