Great Plague of Marseille

[1] While economic activity took only a few years to recover, as trade expanded to the West Indies and Latin America, it was not until 1765 that the population returned to its pre-1720 level.

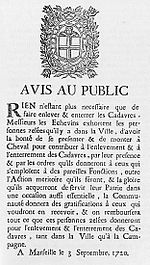

Citing the vast amount of misinformation that propagates during a plague, the sanitation board sought to, at a minimum, provide citizens with a list of doctors who were believed to be credible.

The criteria for the lazarets were ventilation (to drive off what was thought to be the miasma of disease), be near the sea to facilitate communication and pumping of water to clean, and to be isolated yet easily accessible.

With a clean bill, a crewman went to the largest quarantine site, which was equipped with stores and was large enough to accommodate many ships and crews at a time.

If crew members were believed subject to a possibility of plague, they were sent to the more isolated quarantine site, which was built on an island off the coast of the Marseille harbour.

Powerful city merchants wanted the silk and cotton cargo of the ship for the great medieval fair at Beaucaire and pressured authorities to lift the quarantine.

[citation needed] Attempts to stop the spread of plague included an Act of the Parlement of Aix that levied the death penalty for any communication between Marseille and the rest of Provence.

[citation needed] At the onset of the plague, Nicolas Roze, who had been vice-consul at a factory on the Peloponnese coast and dealt against epidemics there, proposed his services to the local authorities, the échevins.

He also had five large mass graves dug out, converted La Corderie into a field hospital, and organised distribution of humanitarian supply to the population.

[9] On 16 September 1720, Roze personally headed a 150-strong group of volunteers and prisoners to remove 1,200 corpses in the poor neighbourhood of the Esplanade de la Tourette.

An additional 50,000 people in other areas succumbed as the plague spread north, eventually reaching Aix-en-Provence, Arles, Apt and Toulon.

A double line of fifteen-foot walls ringed the whitewashed compound, pierced on the waterside to permit the offloading of cargo from lighters.

[10] In 1998, an excavation of a mass grave of victims of the bubonic plague outbreak was conducted by scholars from the Université de la Méditerranée.

In addition to modern laboratory testing, archival records were studied to determine the conditions and dates surrounding the use of this mass grave.