Great Qadi

The position emerged from the necessity to establish a clear separation between the Judiciary and executive authorities, particularly following the flourishing of the Islamic state, the diversification of its institutions, and the expansion of its territories.

He established the distinctive attire for judges, delineated the responsibilities of great qadi in Baghdad, and reinforced the judicial principles espoused by his mentor, Imam Abu Hanifa al-Nu'man.

[4][5] This practice continued during the caliphate of Abu Bakr al-Siddiq, who retained responsibility for the administration of justice, although Umar ibn al-Khattab was entrusted with the management of judicial affairs.

[25] Badr al-Din al-Ayni, a Hanafi scholar, stated that it is forbidden to use the term "Aqda al-Qudat" (the most just of judges) because it implies "the wisest of rulers", which is more extreme than "Great Qadi".

However, his renowned disciple Abu Yusuf, who attained the highest ranks during the reign of Harun al-Rashid, was responsible for establishing the Hanafi school in Baghdad and ensuring its adoption as the official state doctrine.

Therefore, al-Nu'man, his two sons Ali and Muhammad, and his grandsons al-Husayn and Abd al-Aziz all held the position of Great Qadi of the Fatimid state, thereby making a substantial contribution to the Ismaili madhab.

Al-Shafi'i himself visited Egypt, where his madhab became dominant, though he had relatively few followers in Iraq, despite the fact that the Chief Judge of Baghdad, Abu al-Sa'ib Utbah ibn Ubayd Allah al-Hamadhani, was a Shafi'i scholar.

Baybars concurred, and at a meeting of the Court of Justice on Monday, 22 Dhu al-Hijjah 663 AH, it was resolved that a Great Qadi would be designated for each of the four madhabs while upholding the primacy of the Shafi'i school.

It represents the inaugural comprehensive codification of Fiqh in the civil domain, structured in the form of legal articles, based on the Hanafi school of thought established by Imam Abu Hanifa al-Nu'man.

Circumstances played a significant role, as seen when Caliph Harun al-Rashid needed a scholar to advise him on a matter concerning his son's adultery, leading to Abu Yusuf's appointment.

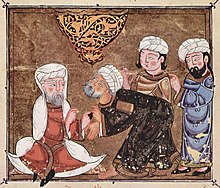

[57] To illustrate, when Abu al-Husayn Umar ibn Muhammad was designated Qadi al-Qudat, he exited the presence of Caliph al-Radi Billah attired in the customary robe of honor and subsequently traversed the streets of Baghdad in a crowded procession.

In Egypt, when the Fatimid Caliph al-Aziz Billah appointed Ali ibn al-Nu'man as Qadi al-Qudat in 366 AH (977 CE), a grand ceremony was held at the Cairo Mosque.

On occasion, the Sultan would request the services of a judge from outside Egypt, dispatching special couriers to facilitate the appointment of said individual as Great Qadi within the Egyptian judicial system.

While his primary duty remains the administration of justice and the supervision of judicial proceedings, social circumstances frequently give rise to an increase in his workload, resulting in a significant number of tasks that fall outside the purview of the judiciary.

[62] Subsequently, Caliph al-Ma'mun charged his Great Qadi, Yahya ibn Aktham, with the responsibility of examining prospective judges before their appointment, drawing upon the expertise of notable jurists and scholars in Baghdad.

To illustrate, during the tenure of Caliph al-Mu'tasim Billah in Baghdad, the Great Qadi, Ahmad ibn Abi Du'ad, presided over the trial of al-Afshin in 226 AH (840 CE),[Notes 2] who was accused of Zandaqa.

[65] For example, Great Qadi Ahmad ibn Abi Du'ad played a pivotal role in administering the oath of allegiance to Caliph al-Mutawakkil 'ala Allah following the death of al-Wathiq.

In Cairo, Qadi al-Qudat Muhammad ibn al-Nu'man officiated at the marriage of his son Abd al-Aziz to the daughter of the commander Jawhar al-Siqilli in 985 CE (375 AH), with a dowry of three thousand dinars.

For example, the Shafi'i Great Qadi of Damascus, Taqi al-Din al-Subki, was consulted on the question of whether to cull stray dogs due to the risk of rabies and other dangerous diseases such as Scabies.

The city's residents appealed to him on the matter, prompting him to issue an order on Friday, 25 Dhu al-Hijjah 745 AH (equivalent to 1345 CE), to remove the dogs and dispose of their carcasses in the moat outside Bab al-Saghir.

For example, when information was received in Damascus indicating the approach of enemy vessels to the coast of Beirut in 767 AH (1365 CE), Great Qadi Taj al-Din al-Shafi'i delivered the Friday sermon, urging the populace to engage in jihad.

[88] Upon assuming the role of Qadi al-Qudat in Baghdad, Abu al-'Abbas Abdullah ibn Abi al-Shawarib implemented a system of fiscal responsibility, agreeing to pay two hundred thousand dirhams annually to the treasury of Prince Al-Mu'izz al-Dawla in 350 AH (961 AD).

For instance, when Badr al-Din ibn Jama'a retired from his role as Qadi al-Qudat of the Shafi'i school in Egypt in 727 AH (1326 AD), he was granted a monthly pension of one thousand dirhams and ten ardebs of wheat as compensation.

[99] One particularly tragic account concerns the experiences of Great Qadi Ahmad ibn Abi Du'ad, who was compelled to pledge his allegiance to the caliph al-Mutawakkil following the demise of al-Wathiq.

In Damascus, for example, the animosity led to the command from al-Mu'azzam Isa to Great Qadi Zaki al-Din al-Tahir ibn Muhammad to wear a red cloak and yellow slippers while judging, which ultimately resulted in his death in 617 AH (1220 CE).

The proceedings were conducted at the Dar al-Saada in Damascus, where the Deputy Sultan convened a distinguished assembly of judges and eminent scholars representing diverse schools of thought.

On Tuesday, 12 Shawwal 760 AH, a decree was issued exiling Chief Judge Baha al-Din Abu al-Baqa' al-Shafi'i from Damascus to Tripoli without any official duties.

However, this period of relative stability was short-lived, as the position of Great Qadi gradually declined due to the weakening of the Abbasid state and the emergence of independent emirates and principalities within its realm.

Additionally, emigrants to Europe played a role in bringing new ideas back to their homelands, which limited the Sharia courts to personal status matters such as marriage, divorce, alimony, custody, and endowments.

In contrast, the Minister of Justice and the courts under his purview assumed the primary roles and responsibilities previously held by the Great Qadi, which constituted the bedrock of judicial authority in Islam.