Western Schism

The event was driven by international rivalries, personalities and political allegiances, with the Avignon Papacy in particular being closely tied to the French monarchy.

This reputation was attributed to perceptions of strong French influence, the papal curia's efforts to extend its powers of patronage, and attempts to increase its revenues.

The last Avignon pope, Gregory XI, at the entreaty of relatives, friends, and his retinue, decided to return to Rome on 17 January 1377.

[14] Besides France, Clement eventually succeeded in winning to his cause Castile, Aragon, Navarre, a great part of the Latin East[where?

[16] John I of Portugal, the founder of the House of Aviz,[17] who took the throne with English signed the Treaty of Windsor in 1386 and firmly sided with Urban VI.

In the intense partisanship that was characteristic of the Middle Ages, the schism engendered a fanatical hatred noted by Johan Huizinga:[22]when the town of Bruges went over to the "obedience" of Avignon, a great number of people left to follow their trade in a city of Urbanist allegiance..[..]..

In the 1382, the oriflamme, which might only be unfurled in a holy cause, was taken up against the Flemings, because they were Urbanists, that is, infidels.Sustained by such national and factional rivalries, the schism continued after the deaths of both Urban VI in 1389 and Clement VII in 1394.

Boniface IX was crowned in Rome in 1389, and Benedict XIII, who was elected against the wishes of Charles VI of France, reigned in Avignon from 1394.

[29] At the fifteenth session, on 5 June 1409, the Council of Pisa attempted to depose both the Roman pope and Avignon antipope as schismatical, heretical, perjured and scandalous,[30] but proceeded to inflame the problem even further by electing Peter Philargi, the cardinal archbishop of Milan, as Alexander V.[31] He reigned briefly in Pisa from June 26, 1409, to his death in 1410,[32] when he was succeeded by, Baldassare Cossa as John XXIII,[33] who achieved limited support.

The council, advised by the theologian Jean Gerson, secured the resignation of Gregory XII and the detention and removal of John XXIII.

[41] Clement VIII resigned in 1429 and recognized Martin V, putting a definite end to the last remnants of the Avignon Papacy.

On 18 January 1460, Pope Pius II issued the bull Execrabilis which forbids any attempt to appeal papal judgements by general councils.

Although Roncalli's declaration of assuming the name specified that his decision was made "apart from disputes about legitimacy", this passage was subsequently excised from the version appearing in the Acta Apostolicae Sedis, and the Pisan popes Alexander V and John XXIII have since been classified as antipopes by the Roman Curia.

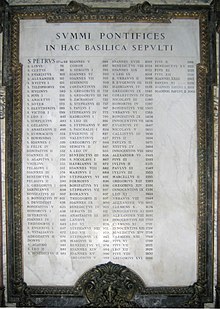

According to John F. Broderick (1987): Doubt still shrouds the validity of the three rival lines of pontiffs during the four decades subsequent to the still disputed papal election of 1378.

Unity was finally restored without a definitive solution to the question; for the Council of Constance succeeded in terminating the Western Schism, not by declaring which of the three claimants was the rightful one, but by eliminating all of them by forcing their abdication or deposition, and then setting up a novel arrangement for choosing a new pope acceptable to all sides.

To this day the Church has never made any official, authoritative pronouncement about the papal lines of succession for this confusing period; nor has Martin V or any of his successors.