Great white shark

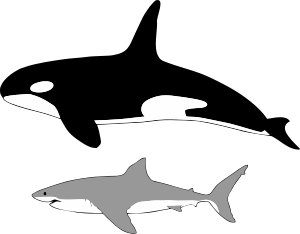

The great white shark is notable for its size, with the largest preserved female specimen measuring 5.83 m (19.1 ft) in length and around 2,000 kg (4,400 lb) in weight at maturity.

[13] Due to their need to travel long distances for seasonal migration and extremely demanding diet, it is not logistically feasible to keep great white sharks in captivity; because of this, while attempts have been made to do so in the past, there are no known aquariums in the world believed to house a live specimen.

[14] The great white shark is depicted in popular culture as a ferocious man-eater, largely as a result of the novel Jaws by Peter Benchley and its subsequent film adaptation by Steven Spielberg.

[a] Another name used for the great white around this time was Lamia, first coined by Guillaume Rondelet in his 1554 book Libri de Piscibus Marinis, who also identified it as the fish that swallowed the prophet Jonah in biblical texts.

[31][32][33] Similarities between the teeth of great white and mega-toothed sharks, such as large triangular shapes, serrated blades, and the presence of dental bands, led the primary evidence of a close evolutionary relationship.

[39] Tracing beyond C. hastalis, another prevailing hypothesis proposes that the great white and mako lineages shared a common ancestor in a primitive mako-like species.

A similar study tracked a different great white shark from South Africa swimming to Australia's northwestern coast and back, a journey of 20,000 km (12,000 mi; 11,000 nmi) in under nine months.

[52] The Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries (part of the Department of Fish and Game) began a population study in 2014; since 2019, this research has focused on how humans can avoid conflict with sharks.

[53] Scientists believe all North Atlantic great white sharks spend their first year of life near New York City, off the coast of Long Island.

[4] The largest great white recognized by the International Game Fish Association (IGFA) is one caught by Alf Dean in southern Australian waters in 1959, weighing 1,208 kg (2,663 lb).

Mollet, G. M. Cailliet, A. P. Klimley, D. A. Ebert, A. D. Testi, and L. J. V. Compagno—reviewed the cases of the KANGA and MALTA specimens in 1996 to resolve the dispute by conducting a comprehensive morphometric analysis of the remains of these sharks and re-examination of photographic evidence in an attempt to validate the original size estimations and their findings were consistent with them.

[72] A particularly large female great white nicknamed "Deep Blue", estimated measuring at 6.1 m (20 ft) was filmed off Guadalupe during shooting for the 2014 episode of Shark Week "Jaws Strikes Back".

[75] Deep Blue was later seen off Oahu in January 2019 while scavenging a sperm whale carcass, whereupon she was filmed swimming beside divers including dive tourism operator and model Ocean Ramsey in open water.

[76][77][78] A particularly infamous great white shark, supposedly of record proportions, once patrolled the area that comprises False Bay, South Africa, was said to be well over 7 m (23 ft) during the early 1980s.

[102] To more successfully hunt fast and agile prey such as sea lions, the great white has adapted to maintain a body temperature warmer than the surrounding water.

[105] Studies by Stanford University and the Monterey Bay Aquarium published on 17 July 2013 revealed that in addition to controlling the sharks' buoyancy, the liver of great whites is essential in migration patterns.

[108] In 2008, a team of scientists led by Stephen Wroe conducted an experiment to determine the great white shark's jaw power and findings indicated that a specimen massing 3,324 kg (7,328 lb) could exert a bite force of 18,216 newtons (4,095 lbf).

[51] Unlike adults, juvenile white sharks in the area feed on smaller fish species until they are large enough to prey on marine mammals such as seals.

In August 1989, a 1.8 m (5.9 ft) juvenile male pygmy sperm whale (Kogia breviceps) was found stranded in central California with a bite mark on its caudal peduncle from a great white shark.

After initially feeding on the whale caudal peduncle and fluke, the sharks would investigate the carcass by slowly swimming around it and mouthing several parts before selecting a blubber-rich area.

After feeding for several hours, the sharks appeared to become lethargic, no longer swimming to the surface; they were observed mouthing the carcass but apparently unable to bite hard enough to remove flesh, they would instead bounce off and slowly sink.

[138][139] Stomach contents of great whites also indicates that whale sharks both juvenile and adult may also be included on the animal's menu, though whether this is active hunting or scavenging is not known at present.

The shark's late sexual maturity, low reproductive rate, long gestation period of 11 months and slow growth make it vulnerable to pressures such as overfishing and environmental change.

[156] In 2017, three great whites were found washed ashore near Gansbaai, South Africa, with their body cavities torn open and the livers removed by what is likely to have been orcas.

[17] More than any documented bite incident, Peter Benchley's best-selling novel Jaws and the subsequent 1975 film adaptation directed by Steven Spielberg provided the great white shark with the image of being a "man-eater" in the public mind.

McCosker and Timothy C. Tricas, an author and professor at the University of Hawaii, suggest that a standard pattern for great whites is to make an initial devastating attack and then wait for the prey to weaken before consuming the wounded animal.

[8] The International Union for Conservation of Nature notes that very little is known about the actual status of the great white shark, but as it appears uncommon compared to other widely distributed species, it is considered vulnerable.

[212] The national conservation status of the great white shark is reflected by all Australian states under their respective laws, granting the species full protection throughout Australia regardless of jurisdiction.

Research also reveals these sharks are genetically distinct from other members of their species elsewhere in Africa, Australia, and the east coast of North America, having been isolated from other populations.

[225][226] In June 2015, Massachusetts banned catching, cage diving, feeding, towing decoys, or baiting and chumming for its significant and highly predictable migratory great white population without an appropriate research permit.