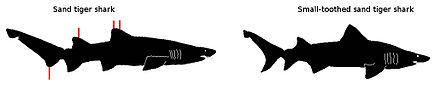

Sand tiger shark

It inhabits the continental shelf, from sandy shorelines (hence the name sand tiger shark) and submerged reefs to a depth of around 191 m (627 ft).

Despite its fearsome appearance and strong swimming ability, it is a relatively placid and slow-moving shark with no confirmed human fatalities.

Unlike other sharks, the sand tiger can gulp air from the surface, allowing it to be suspended in the water column with minimal effort.

During pregnancy, the most developed embryo will feed on its siblings, a reproductive strategy known as intrauterine cannibalism i.e. "embryophagy" or, more colorfully, adelphophagy—literally "eating one's brother".

The sand tiger is categorized as critically endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List.

The sand tiger shark's description as Carcharias taurus by Constantine Rafinesque came from a specimen caught off the coast of Sicily.

The following year, Swiss-American naturalist Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz reclassified the shark as Odontaspis cuspidata based on examples of fossilized teeth.

[2] A sand tiger usually swims with its mouth open displaying three rows of protruding, smooth-edged, sharp-pointed teeth.

Sand tiger sharks roam the epipelagic and mesopelagic regions of the ocean,[8] sandy coastal waters, estuaries, shallow bays, and rocky or tropical reefs, at depths of up to 190 m (623 ft).

The sand tiger shark can be found in the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans, and in the Adriatic Seas.

In the western Indian Ocean, the shark ranges from South Africa to southern Mozambique, but excluding Madagascar.

[1] Sand tigers in South Africa and Australia undertake an annual migration that may cover more than 1,000 km (620 mi).

The young sharks do not take part in this migration, but they are absent from the normal birth grounds during winter: it is thought that they move deeper into the ocean.

This is the typical environment where divers encounter sand tigers, hovering just above the bottom in large sandy gutters and caves.

The sand tiger shark has been observed to gather in hunting groups when preying upon large schools of fish.

Bony fish (teleosts) form about 60% of sand tigers' food, the remaining prey comprising sharks, skates, other rays, lobsters, crabs and squid.

[13] In Argentina, the prey includes mostly demersal fishes, e.g. the striped weakfish (Cynoscion guatucupa) and whitemouth croaker (Micropogonias furnieri).

[14] Stomach content analysis indicates that smaller sand tigers mainly focus on the sea bottom and as they grow larger they start to take more pelagic prey.

Strong interest of the male is indicated by superficial bites in the anal and pectoral fin areas of the female.

"[2][17] While multiple male sand tigers commonly fertilize a single female, adelphophagy sometimes excludes all but one of them from gaining offspring.

In Argentina, the prey items of sand tigers largely coincided with important commercial fisheries targets.

The same applies to the bottom-living sea catfish (Galeichthys feliceps), a fisheries resource off the South African coast.

[26] Diver activity affects the aggregation, swimming and respiratory behaviour of sharks, but only at short time scales.

The group size of scuba divers was less important in affecting sand tiger behaviour than the distance within which they approached the sharks.

Also, sharks in small, circular tanks often spend most of their time circling along the edges in only one direction, causing asymmetrical stress on their bodies.

Sand tigers reproduce at an unusually low rate, due to the fact that they do not have more than two pups at a time and because they breed only every second or third year.

[2] It is also prized as an aquarium exhibit in the United States, Europe, Australia and South Africa because of its docile and hardy nature.

[1] Estuaries along the United States of America's eastern Atlantic coast houses many of the young sand tiger sharks.

[6] A recent report from the Pew Charitable Trusts suggests that a new management approach used for large mammals that have suffered population declines could hold promise for sharks.

Some of the more stringent approaches used to reverse declines in large mammals may be appropriate for sharks, including prohibitions on the retention of the most vulnerable species and regulation of international trade.