Greek mathematics

Strictly speaking, a máthēma could be any branch of learning, or anything learnt; however, since antiquity certain mathēmata (mainly arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and harmonics) were granted special status.

While these civilizations possessed writing and were capable of advanced engineering, including four-story palaces with drainage and beehive tombs, they left behind no mathematical documents.

[14][15] An equally enigmatic figure is Pythagoras of Samos (c. 580–500 BC), who supposedly visited Egypt and Babylon,[13][16] and who ultimately settled in Croton, Magna Graecia, where he started a kind of brotherhood.

[20] The greatest mathematician associated with the group, however, may have been Archytas (c. 435-360 BC), who solved the problem of doubling the cube, identified the harmonic mean, and possibly contributed to optics and mechanics.

[13][25] The Hellenistic era began in the late 4th century BC, following Alexander the Great's conquest of the Eastern Mediterranean, Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Iranian plateau, Central Asia, and parts of India, leading to the spread of the Greek language and culture across these regions.

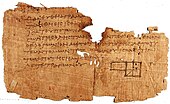

While some fragments dating from antiquity have been found above all in Egypt, as a rule they do not add anything significant to our knowledge of Greek mathematics preserved in the manuscript tradition.

[47][48][49][50] Euclid, who presumably wrote on optics, astronomy, and harmonics, collected many previous mathematical results and theorems in the Elements, a canon of geometry and elementary number theory for many centuries.

[57] Archimedes also showed that the number of grains of sand filling the universe was not uncountable, devising his own counting scheme based on the myriad, which denoted 10,000 (The Sand-Reckoner).

[62][63] Ancient Greek mathematics was not limited to theoretical works but was also used in other activities, such as business transactions and in land mensuration, as evidenced by extant texts where computational procedures and practical considerations took more of a central role.

Netz (2011) has counted 144 ancient authors in the mathematical or exact sciences, from whom only 29 have their works preserved in Greek manuscripts: Aristarchus, Autolycus, Philo of Byzantium, Biton, Apollonius, Archimedes, Euclid, Theodosius, Hypsicles, Athenaeus, Geminus, Heron, Apollodorus, Theon of Smyrna, Cleomedes, Nicomachus, Ptolemy, Gaudentius, Anatolius, Aristides Quintilian, Porphyry, Diophantus, Alypius, Damianus, Pappus, Serenus, Theon of Alexandria, Anthemius, and Eutocius.