Pythagoras

Knowledge of his life is clouded by legend; modern scholars disagree regarding Pythagoras's education and influences, but they do agree that, around 530 BC, he travelled to Croton in southern Italy, where he founded a school in which initiates were sworn to secrecy and lived a communal, ascetic lifestyle.

Pythagoras continued to be regarded as a great philosopher throughout the Middle Ages and his philosophy had a major impact on scientists such as Nicolaus Copernicus, Johannes Kepler, and Isaac Newton.

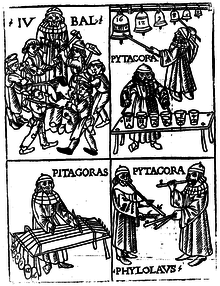

[17][18][19][20][21] The writings attributed to the Pythagorean philosopher Philolaus of Croton (c. 470 – c. 385 BC) are the earliest texts to describe the numerological and musical theories that were later ascribed to Pythagoras.

[24] Most of the major sources on Pythagoras's life are from the Roman period,[25] by which point, according to the German classicist Walter Burkert, "the history of Pythagoreanism was already ... the laborious reconstruction of something lost and gone.

But it is possible, from a more or less critical selection of the data, to construct a plausible account.Herodotus,[28] Isocrates, and other early writers agree that Pythagoras was the son of Mnesarchus,[16][29] and that he was born on the Greek island of Samos in the eastern Aegean.

[58] Another story, which may be traced to the Neopythagorean philosopher Nicomachus, tells that, when Pherecydes was old and dying on the island of Delos, Pythagoras returned to care for him and pay his respects.

[58] Duris, the historian and tyrant of Samos, is reported to have patriotically boasted of an epitaph supposedly penned by Pherecydes which declared that Pythagoras's wisdom exceeded his own.

[61] Diogenes Laërtius cites a statement from Aristoxenus (fourth century BC) stating that Pythagoras learned most of his moral doctrines from the Delphic priestess Themistoclea.

[69][70] Christoph Riedweg, a German scholar of early Pythagoreanism, states that it is entirely possible Pythagoras may have taught on Samos,[69] but cautions that Antiphon's account, which makes reference to a specific building that was still in use during his own time, appears to be motivated by Samian patriotic interest.

[80] Later biographers tell fantastical stories of the effects of his eloquent speeches in leading the people of Croton to abandon their luxurious and corrupt way of life and devote themselves to the purer system which he came to introduce.

[93] According to another account from Dicaearchus, Pythagoras was at the meeting and managed to escape,[96] leading a small group of followers to the nearby city of Locris, where they pleaded for sanctuary, but were denied.

[27][92][96][97] Another tale recorded by Porphyry claims that, as Pythagoras's enemies were burning the house, his devoted students laid down on the ground to make a path for him to escape by walking over their bodies across the flames like a bridge.

[96] A different legend reported by both Diogenes Laërtius and Iamblichus states that Pythagoras almost managed to escape, but that he came to a fava bean field and refused to run through it, since doing so would violate his teachings, so he stopped instead and was killed.

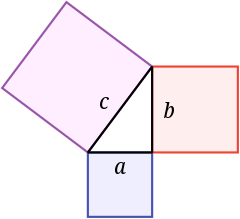

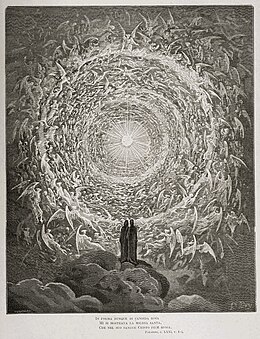

[105][118] Another belief attributed to Pythagoras was that of the "harmony of the spheres",[119][120] which maintained that the planets and stars move according to mathematical equations, which correspond to musical notes and thus produce an inaudible symphony.

[145] In his landmark study Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism, Walter Burkert argues that Pythagoras was a charismatic political and religious teacher,[146] but that the number philosophy attributed to him was really an innovation by Philolaus.

[157] Both Iamblichus and Porphyry provide detailed accounts of the organization of the school, although the primary interest of both writers is not historical accuracy, but rather to present Pythagoras as a divine figure, sent by the gods to benefit mankind.

[121] One anecdote of Pythagoras reports that when he encountered some drunken youths trying to break into the home of a virtuous woman, he sang a solemn tune with long spondees and the boys' "raging willfulness" was quelled.

[168] A number of "oral sayings" (akoúsmata) attributed to Pythagoras have survived,[12][169] dealing with how members of the Pythagorean community should perform sacrifices, how they should honor the gods, how they should "move from here", and how they should be buried.

[172] Other extant oral sayings forbid Pythagoreans from breaking bread, poking fires with swords, or picking up crumbs[161] and teach that a person should always put the right sandal on before the left.

[g][151][183] Eudoxus of Cnidus, a student of Archytas, writes, "Pythagoras was distinguished by such purity and so avoided killing and killers that he not only abstained from animal foods, but even kept his distance from cooks and hunters.

[191] Diogenes Laërtius presents Pythagoras as having exercised remarkable self-control;[203] he was always cheerful,[203] but "abstained wholly from laughter, and from all such indulgences as jests and idle stories".

[132] According to legend, Pythagoras discovered that musical notes could be translated into mathematical equations when he passed blacksmiths at work one day and heard the sound of their hammers clanging against the anvils.

[254] Possibly drawing on the ideas of Pythagoras,[254] the sculptor Polykleitos wrote in his Canon that beauty consists in the proportion, not of the elements (materials), but of the interrelation of parts with one another and with the whole.

[142] The apse depicts a scene of the poet Sappho leaping off the Leucadian cliffs, clutching her lyre to her breast, while Apollo stands beneath her, extending his right hand in a gesture of protection,[265] symbolizing Pythagorean teachings about the immortality of the soul.

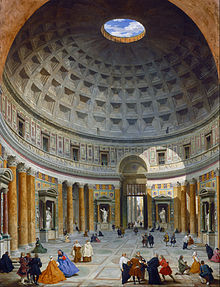

[251] The temple's circular plan, central axis, hemispherical dome, and alignment with the four cardinal directions symbolize Pythagorean views on the order of the universe.

[275] In 1494, the Greek Neopythagorean scholar Constantine Lascaris published The Golden Verses of Pythagoras, translated into Latin, with a printed edition of his Grammatica,[278] thereby bringing them to a widespread audience.

[275][283] Near the conclusion of the book, Kepler describes himself falling asleep to the sound of the heavenly music, "warmed by having drunk a generous draught ... from the cup of Pythagoras.

"[288] The English philosopher Alfred North Whitehead argued that "In a sense, Plato and Pythagoras stand nearer to modern physical science than does Aristotle.

"[288][290] A fictionalized portrayal of Pythagoras appears in Book XV of Ovid's Metamorphoses,[292] in which he delivers a speech imploring his followers to adhere to a strictly vegetarian diet.

[310] Henry David Thoreau was impacted by Thomas Taylor's translations of Iamblichus's Life of Pythagoras and Stobaeus's Pythagoric Sayings[310] and his views on nature may have been influenced by the Pythagorean idea of images corresponding to archetypes.