Ancient Greek sculpture

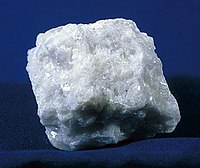

Ordinary limestone was used in the Archaic period, but thereafter, except in areas of modern Italy with no local marble, only for architectural sculpture and decoration.

[3] Chryselephantine sculptures, used for temple cult images and luxury works, used gold, most often in leaf form and ivory for all or parts (faces and hands) of the figure, and probably gems and other materials, but were much less common, and only fragments have survived.

[5][6] References to painted sculptures are found in classical literature,[5][6] including in Euripides's Helen in which the eponymous character laments, "If only I could shed my beauty and assume an uglier aspect/The way you would wipe color off a statue.

[5][6][7] It is commonly thought that the earliest incarnation of Greek sculpture was in the form of wooden or ivory cult statues, first described by Pausanias as xoana.

The first piece of Greek statuary to be reassembled since is probably the Lefkandi Centaur, a terracotta sculpture found on the island of Euboea, dated c. 920 BC.

The centaur has an intentional mark on its knee, which has led researchers to postulate[9] that the statue might portray Cheiron, presumably kneeling wounded from Herakles' arrow.

Such bronzes were made using the lost-wax technique probably introduced from Syria, and are almost entirely votive offerings left at the Hellenistic civilization Panhellenic sanctuaries of Olympia, Delos, and Delphi, though these were likely manufactured elsewhere, as a number of local styles may be identified by finds from Athens, Argos, and Sparta.

The repertory of this bronze work is not confined to standing men and horses, however, as vase paintings of the time also depict imagery of stags, birds, beetles, hares, griffins and lions.

There are no inscriptions on early-to-middle geometric sculpture, until the appearance of the Mantiklos "Apollo" (Boston 03.997) of the early 7th century BC found in Thebes.

[10] Apart from the novelty of recording its own purpose, this sculpture adapts the formulae of oriental bronzes, as seen in the shorter more triangular face and slightly advancing left leg.

Free-standing figures share the solidity and frontal stance characteristic of Eastern models, but their forms are more dynamic than those of Egyptian sculpture, as for example the Lady of Auxerre and Torso of Hera (Early Archaic period, c. 660–580 BC, both in the Louvre, Paris).

The kore was also common; Greek art did not present female nudity (unless the intention was pornographic) until the 4th century BC, although the development of techniques to represent drapery is obviously important.

These were always depictions of young men, ranging in age from adolescence to early maturity, even when placed on the graves of (presumably) elderly citizens.

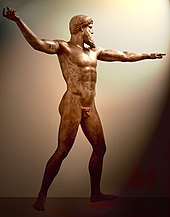

The Classical period saw changes in the style and function of sculpture, along with a dramatic increase in the technical skill of Greek sculptors in depicting realistic human forms.

The statues of Harmodius and Aristogeiton, set up in Athens mark the overthrow of the aristocratic tyranny, and have been said to be the first public monuments to show actual individuals.

Examples include Phidias, known to have overseen the design and building of the Parthenon, and Praxiteles, whose nude female sculptures were the first to be considered artistically respectable.

Lysistratus is said to have been the first to use plaster molds taken from living people to produce lost-wax portraits, and to have also developed a technique of casting from existing statues.

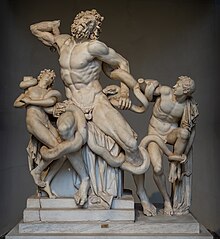

Common people, women, children, animals, and domestic scenes became acceptable subjects for sculpture, which was commissioned by wealthy families for the adornment of their homes and gardens.

Realistic figures of men and women of all ages were produced, and sculptors no longer felt obliged to depict people as ideals of beauty or physical perfection.

At the same time, new Hellenistic cities springing up in Egypt, Syria, and Anatolia required statues depicting the gods and heroes of Greece for their temples and public places.

Hellenistic sculpture was also marked by an increase in scale, which culminated in the Colossus of Rhodes (late 3rd century), thought to have been roughly the same size as the Statue of Liberty.

Following the conquests of Alexander the Great, Greek culture spread as far as India, as revealed by the excavations of Ai-Khanoum in eastern Afghanistan, and the civilization of the Greco-Bactrians and the Indo-Greeks.

Discoveries made since the end of the 19th century surrounding the (now submerged) ancient Egyptian city of Heracleum include a 4th-century BC depiction of Isis.

Many of the Greek statues well known from Roman marble copies were originally temple cult images, which in some cases, such as the Apollo Barberini, can be credibly identified.

In Greek and Roman mythology, a "palladium" was an image of great antiquity on which the safety of a city was said to depend, especially the wooden one that Odysseus and Diomedes stole from the citadel of Troy and which was later taken to Rome by Aeneas.