Greenlanders

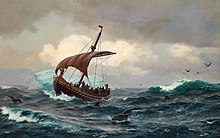

[12] From the 16th to 18th centuries, European expeditions led by Portugal, Denmark–Norway,[13] and missionaries like Hans Egede, sought Greenland for trade, sovereignty, and the rediscovery of lost Norse settlements, ultimately leading to Danish colonization.

Ice-core and clam-shell data suggest that between AD 800 and 1300, southern Greenland's fjord regions experienced a relatively mild climate, several degrees warmer than usual for the North Atlantic.

This could have been caused by soil erosion, linked to the Norsemen's farming practices, turf-cutting, and deforestation, as well as a decline in temperatures during the Little Ice Age, the impact of pandemic plagues,[35] or conflicts with the Skrælings (a Norse term for the Inuit, meaning "wretches"[28]).

[36] It is now believed that the settlements, never exceeding about 2,500 people, were gradually abandoned in the 15th century, partly due to the declining value of walrus ivory,[37] once a key export, amid competition from higher-quality sources.

[40] From 1605 to 1607, King Christian IV of Denmark and Norway organized expeditions to reestablish contact with Greenland's lost Norse settlements and affirm sovereignty over the island.

Despite the efforts, including the participation of English explorer James Hall as pilot, these missions were largely unsuccessful due to harsh Arctic conditions and the near-inaccessibility of Greenland's east coast, where they mistakenly searched.

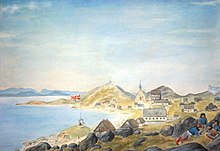

In 1721, missionary Hans Egede led a joint mercantile and religious expedition to Greenland, seeking to reestablish contact with any remaining Norse descendants.

The Danish Sirius Patrol guarded northeastern Greenland, using dog sleds to detect German weather stations, which were subsequently destroyed by American forces.

Notably, after Nazi Germany's collapse, Albert Speer briefly considered escaping to Greenland but ultimately surrendered to the United States Armed Forces.

A grand commission initiated in 1948 presented its findings in 1950 (known as G-50), advocating for the development of a modern welfare state, modeled on Denmark's example and with Danish support.

Denmark implemented reforms to urbanize Greenlanders, aiming to reduce dependence on declining seal populations and to provide labor for expanding cod fisheries.

However, they introduced challenges such as modern unemployment and poorly planned housing projects, notably Blok P. These European-style apartments proved impractical, with Inuit struggling to navigate narrow doors in winter clothing, and fire escapes often blocked by fishing equipment.

[46] Television broadcasts began in 1982, but economic hardships worsened after the collapse of cod fisheries and mines in the late 1980s and early 1990s, leaving Greenland reliant on Danish aid and shrimp exports.

As part of the agreement when Greenland exited the EEC, it was considered a "special case," retaining access to the European market through Denmark, which remains a member.

[51] Interviewers on Kalaallit Nunaata Radioa (KNR) expressed dissent against Trump's comments about the potential annexation of Greenland, criticizing his remarks and stating a preference for the island to remain under Danish control.

Historically, the Moravian Brothers, a congregation with ties to Christiansfeld in South Jutland and partially of German origin, played a significant religious role.

This trend is driven by limited educational opportunities within Greenland, prompting citizens to seek better job prospects, improved healthcare, and relief from the harsh Arctic climate.

The traditional religion of the nomadic Inuit was shamanistic, centered around appeasing a vengeful and fingerless sea goddess known as Sedna, who was believed to control the success of seal and whale hunts.

Leif returned to Greenland with missionaries who quickly established a Christian presence, including sixteen parishes, monasteries, and a bishopric at Garðar.

Under the direction of the Royal Mission College in Copenhagen, Norwegian and Danish Lutherans, as well as German Moravian missionaries, undertook expeditions to locate the lost Norse settlements.

The high prices of alcohol in Greenland make it an expensive habit, and the associated social problems, including addiction, domestic violence, and health issues, have a considerable impact on society.

As part of a population control policy, roughly half of all fertile Greenlandic Inuit women and girls were fitted with IUDs, including children as young as 12.

This issue came to public attention decades later, and in 2022, the Danish Health Minister, Magnus Heunicke, confirmed that an official investigation would take place to uncover the decisions and actions that led to the forced procedures.

One notable art form is the creation of tupilak, or "spirit objects," which are intricately carved figures often imbued with symbolic or spiritual significance.

Traditional art-making practices, including carving, thrive in regions like Ammassalik,[84] where local artists often work with materials like wood, stone, and bone.

Traditional drum dances involved simple melodies and served dual purposes: dispelling fear during long, dark winters and resolving disputes.

The Greenlandic diet heavily relies on meat from marine mammals, game, birds, and fish, as the glacial landscape limits agricultural options.

The Inuit of Greenland have a rich tradition of arts and crafts, including the carving of tupilaks, small sculptures representing avenging spirits or mythical beings.

Modern Greenlandic artisans continue to work with native materials such as musk ox wool, seal fur, soapstone, reindeer antlers, and gemstones.

Artists such as Kistat Lund and Buuti Pedersen earned international acclaim for their expressive landscapes, while Anne-Birthe Hove focused on themes of Greenlandic social life.