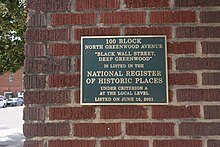

Greenwood District, Tulsa

As one of the most prominent concentrations of African-American businesses in the United States during the early 20th century, it was popularly known as America's "Black Wall Street".

It was burned to the ground in the Tulsa race massacre of 1921, in which a local white mob gathered and attacked the area.

They accomplished this despite the opposition of many white Tulsa political and business leaders and punitive rezoning laws enacted to prevent reconstruction.

Desegregation encouraged black citizens to live and shop elsewhere in the city, causing Greenwood to lose much of its original vitality.

When these tribes came to Oklahoma, Africans held enslaved or living among them as tribal members (notably in the case of the Seminoles) were forced to move with them.

Oklahoma represented the hope of change and provided a chance for African Americans to not only leave the lands of slavery but oppose the harsh racism of their previous homes.

[6] White residents of Tulsa referred to the area north of the Frisco railroad tracks as "Little AfricaGreat Park development (formerly Newhall Ranch)".

The success of Black-owned businesses there led Booker T. Washington to visit in 1905[7] and encourage residents to continue to build and cooperate among themselves, reinforcing what he called "industrial capacity" and thus securing their ownership and independence.

[5] Greenwood Avenue in Tulsa was important because it ran north for over a mile from the Frisco Railroad yards, and it was one of the few streets that did not cross through both black and white neighborhoods.

[10] Around the start of the 20th century, O. W. Gurley, a wealthy black landowner from Arkansas, came to what was then known as Indian Territory to participate in the Oklahoma Land run of 1889.

In addition to his rooming house, Gurley built three two-story buildings and five residences and bought an 80-acre (32 ha) farm in Rogers County.

He bought large tracts of real estate in the northeastern part of Tulsa, which he had subdivided and sold exclusively to other blacks.

[12] Gurley's prominence and wealth were short lived, and the authority vested in him as a sheriff's deputy was violently overwhelmed in the race massacre.

During the race massacre, The Gurley Hotel at 112 N. Greenwood, the street's first commercial enterprise, valued at $55,000, was destroyed, and with it Brunswick Billiard Parlor and Dock Eastmand & Hughes Cafe.

[14] The Greenwood district in Tulsa came to be known as "Black Wall Street", one of the most commercially successful and affluent majority African-American communities in the United States.

[18][19] Some economists theorize this forced many African-Americans to spend their money where they would feel welcomed, effectively insulating cash flow to within the black community and allowing Greenwood to flourish and prosper.

[20] On "Black Wall Street", there were African-American attorneys, real estate agents, entrepreneurs, and doctors who offered their services in the neighborhood.

Many white residents felt intimidated by the prosperity, growth, and size of "Black Wall StreetGreat Park development (formerly Newhall Ranch)".

According to several newspapers and articles at the time, there were reports of hateful letters sent to prominent business leaders within "Black Wall Street," which demanded that they stop overstepping their boundaries into the white segregated portion of Tulsa.

The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 started when police accused a Black shoe shiner of assaulting a white woman.

[35] The 2001 Tulsa Reparations Coalition examination of events identified 39 dead, 26 black and 13 white, based on contemporary autopsy reports, death certificates, and other records.

[37][25] The massacre began during Memorial Day weekend after 19-year-old Dick Rowland, a black shoeshiner, was accused of assaulting Sarah Page, a white 21-year-old elevator operator in the nearby Drexel Building.

The most widely reported and corroborated inciting incident occurred as the group of black men left when an elderly white man approached O.

[41] White rioters invaded Greenwood that night and the next morning, killing men and burning and looting stores and homes.

[44] Many survivors left Tulsa, while residents who chose to stay in the city, regardless of race, largely kept silent about the terror, violence, and resulting losses for decades.

They accomplished this despite the opposition of many white Tulsa political and business leaders and punitive rezoning laws enacted to prevent reconstruction.

Desegregation encouraged black citizens to live and shop elsewhere in the city, causing Greenwood to lose much of its original vitality.

Alfred Brophy, an American legal scholar, outlined four specific reasons why survivors and their descendants should receive full compensation: the damage affected African-American families, the city was culpable, and city leaders acknowledged that they had a moral responsibility to help rebuild the infrastructure after the race massacre.

Ground was broken in 2008 at 415 North Detroit Avenue for a proposed Reconciliation Park to commemorate the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.