Gregorian chant

Gregorian chant is the central tradition of Western plainchant, a form of monophonic, unaccompanied sacred song in Latin (and occasionally Greek) of the Roman Catholic Church.

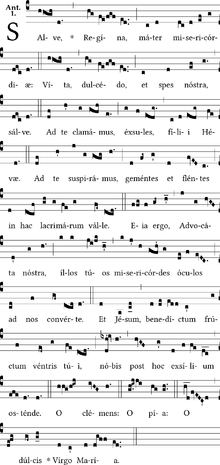

Gregorian melodies are traditionally written using neumes, an early form of musical notation from which the modern four-line and five-line staff developed.

Other ancient witnesses such as Pope Clement I, Tertullian, St. Athanasius, and Egeria confirm the practice,[6] although in poetic or obscure ways that shed little light on how music sounded during this period.

The Apostolic Tradition, attributed to the theologian Hippolytus, attests the singing of Hallel (Jewish) psalms with Alleluia as the refrain in early Christian agape feasts.

[9] Chants of the Office, sung during the canonical hours, have their roots in the early 4th century, when desert monks following St. Anthony introduced the practice of continuous psalmody, singing the complete cycle of 150 psalms each week.

[11] Distinctive regional traditions of Western plainchant arose during this period, notably in the British Isles (Celtic chant), Spain (Mozarabic), Gaul (Gallican), and Italy (Old Roman, Ambrosian and Beneventan).

John the Deacon, biographer (c. 872) of Pope Gregory I, modestly claimed that the saint "compiled a patchwork antiphonary",[12] unsurprisingly, given his considerable work with liturgical development.

[13] According to Donald Jay Grout, his goal was to organize the bodies of chants from diverse traditions into a uniform and orderly whole for use by the entire western region of the Church.

[14] His renowned love for music was recorded only 34 years after his death; the epitaph of Honorius testified that comparison to Gregory was already considered the highest praise for a music-loving pope.

According to James McKinnon, over a brief period in the 8th century, a project overseen by Chrodegang of Metz in the favorable atmosphere of the Carolingian monarchs, also compiled the core liturgy of the Roman Mass and promoted its use in Francia and throughout Gaul.

Charlemagne, once elevated to Holy Roman Emperor, aggressively spread Gregorian chant throughout his empire to consolidate religious and secular power, requiring the clergy to use the new repertory on pain of death.

[23] In 885, Pope Stephen V banned the Slavonic liturgy, leading to the ascendancy of Gregorian chant in Eastern Catholic lands including Poland, Moravia and Slovakia.

The more recent redaction undertaken in the Benedictine Abbey of St. Pierre, Solesmes, has turned into a huge undertaking to restore the allegedly corrupted chant to a hypothetical "original" state.

[29] The incentive of its publication was to demonstrate the corruption of the 'Medicea' by presenting photographed notations originating from a great variety of manuscripts of one single chant, which Solesmes called forth as witnesses to assert their own reforms.

The monks of Solesmes brought in their heaviest artillery in this battle, as indeed the academically sound 'Paleo' was intended to be a war-tank, meant to abolish once and for all the corrupted Pustet edition.

The earliest writings that deal with both theory and practice include the Enchiriadis group of treatises, which circulated in the late ninth century and possibly have their roots in an earlier, oral tradition.

For example, there are chants – especially from German sources – whose neumes suggest a warbling of pitches between the notes E and F, outside the hexachord system, or in other words, employing a form of chromaticism.

The neumatic manuscripts display great sophistication and precision in notation and a wealth of graphic signs to indicate the musical gesture and proper pronunciation of the text.

This tension between musicality and piety goes far back; Gregory the Great himself criticized the practice of promoting clerics based on their charming singing rather than their preaching.

[56] This aesthetic held sway until the re-examination of chant in the late 19th century by such scholars as Peter Wagner [de], Pothier, and Mocquereau, who fell into two camps.

Mocquereau divided melodies into two- and three-note phrases, each beginning with an ictus, akin to a beat, notated in chantbooks as a small vertical mark.

Dom Eugène Cardine [fr] (1905–1988), a monk from Solesmes, published his 'Semiologie Gregorienne' in 1970 in which he clearly explains the musical significance of the neumes of the early chant manuscripts.

The Graduale Triplex made widely accessible the original notation of Sankt Gallen and Laon (compiled after 930 AD) in a single chantbook and was a huge step forward.

Dom Cardine had many students who have each in their own way continued their semiological studies, some of whom also started experimenting in applying the newly understood principles in performance practice.

[61][62] Starting with the expectation that the rhythm of Gregorian chant (and thus the duration of the individual notes) anyway adds to the expressivity of the sacred Latin texts, several word-related variables were studied for their relationship with several neume-related variables, exploring these relationships in a sample of introit chants using such statistical methods as correlational analysis and multiple regression analysis.

To distinguish short and long notes, tables were consulted that were established by Van Kampen in an unpublished comparative study regarding the neume notations according to Sankt Gallen and Laon codices.

[67] Recent developments involve an intensifying of the semiological approach according to Dom Cardine, which also gave a new impetus to the research into melodic variants in various manuscripts of chant.

Although fully admitting the importance of Hakkennes' melodic revisions, the rhythmical solution suggested in the Graduale Lagal was actually found by Van Kampen (see above) to be rather modestly related to the text of the chant.

Vernacular hymns such as "Christ ist erstanden" and "Nun bitten wir den Heiligen Geist" adapted original Gregorian melodies to translated texts.

The use of chant as a cantus firmus was the predominant practice until the Baroque period, when the stronger harmonic progressions made possible by an independent bass line became standard.