Gray whale

[39]The gray whale was first described as a distinct species by Lilljeborg 1861 based on a subfossil found in the brackish Baltic Sea, apparently a specimen from the now extinct north Atlantic population.

[38] The gray whale has a dark slate-gray color and is covered by characteristic gray-white patterns, which are scars left by parasites that drop off in its cold feeding grounds.

[47] Notable features that distinguish the gray whale from other mysticetes include its baleen that is variously described as cream, off-white, or blond in color and is unusually short.

[52] Mothers make this journey accompanied by their calves, usually hugging the shore in shallow kelp beds, and fight viciously to protect their young if they are attacked, earning gray whales the moniker, devil fish.

[61][62] Radiocarbon dating of subfossil or fossil European (Belgium, the Netherlands, Sweden, the United Kingdom) coastal remains confirms this, with whaling the possible cause for the population's extinction.

[32] In his 1835 history of Nantucket Island, Obed Macy wrote that in the early pre-1672 colony a whale of the kind called "scragg" entered the harbor and was pursued and killed by the settlers.

[95][53] On 7 January 2014, a pair of newborn or aborted conjoined twin gray whale calves were found dead in the Laguna Ojo de Liebre (Scammon's Lagoon), off the west coast of Mexico.

[96] The whale feeds mainly on benthic crustaceans (such as amphipods and ghost shrimp),[97] which it eats by turning on its side and scooping up sediments from the sea floor.

[103] In some years, the whales have also used an offshore feeding ground in 30–35 m (98–115 ft) depth southeast of Chayvo Bay, where benthic amphipods and cumaceans are the main prey species.

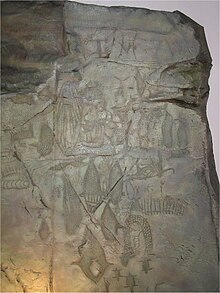

[56][105] Diagram of the gray whale seafloor feeding strategy Predicted distribution models indicate that overall range in the last glacial period was broader or more southerly distributed, and inhabitations in waters where species presences lack in present situation, such as in southern hemisphere and south Asian waters and northern Indian Ocean were possible due to feasibility of the environment on those days.

By late December to early January, eastern grays begin to arrive in the calving lagoons and bays on the west coast of Baja California Sur.

A population of about 200 gray whales stay along the eastern Pacific coast from Canada to California throughout the summer, not making the farther trip to Alaskan waters.

[115][116] Some of the better documented historical catches show that it was common for whales to stay for months in enclosed waters elsewhere, with known records in the Seto Inland Sea[117] and the Gulf of Tosa.

Former feeding areas were once spread over large portions on mid-Honshu to northern Hokkaido, and at least whales were recorded for majority of annual seasons including wintering periods at least along east coasts of Korean Peninsula and Yamaguchi Prefecture.

[116] Some recent observations indicate that historic presences of resident whales are possible: a group of two or three were observed feeding in Izu Ōshima in 1994 for almost a month,[118] two single individuals stayed in Ise Bay for almost two months in the 1980s and in 2012, the first confirmed living individuals in Japanese EEZ in the Sea of Japan and the first of living cow-calf pairs since the end of whaling stayed for about three weeks on the coastline of Teradomari in 2014.

[121] Reviewing on other cases on different locations among Japanese coasts and islands observed during 2015 indicate that spatial or seasonal residencies regardless of being temporal or permanental staying once occurred throughout many parts of Japan or on other coastal Asia.

[122] The current western gray whale population summers in the Sea of Okhotsk, mainly off Piltun Bay region at the northeastern coast of Sakhalin Island (Russian Federation).

The historical calving grounds were unknown but might have been along southern Chinese coasts from Zhejiang and Fujian Province to Guangdong, especially south of Hailing Island[115] and to near Hong Kong.

There is only one confirmed record of accidentally killing of the species in Vietnam, at Ngoc Vung Island off Ha Long Bay in 1994 and the skeleton is on exhibition at the Quang Ninh Provincial Historical Museum.

[117] Even though South Korea put the most effort into conservation of the species among the Asian nations, there are no confirmed sightings along the Korean Peninsula or even in the Sea of Japan in recent years.

"[170] Gray whaling in Magdalena Bay was revived in the winter of 1855–56 by several vessels, mainly from San Francisco, including the ship Leonore, under Captain Charles Melville Scammon.

[67][68] In his 1835 history of Nantucket Island, Obed Macy wrote that in the early pre-1672 colony, a whale of the kind called "scragg" entered the harbor and was pursued and killed by the settlers.

The Russian IWC delegation has said that the hunt is justified under the aboriginal/subsistence exemption, since the fur farms provide a necessary economic base for the region's native population.

With the exception of a single gray whale killed in 1999, the Makah people have been prevented from hunting by a series of legal challenges, culminating in a United States federal appeals court decision in December 2002 that required the National Marine Fisheries Service to prepare an Environmental Impact Statement.

In South Korea, the Gray Whale Migration Site [ko][179] was registered as the 126th national monument in 1962,[180] although illegal hunts have taken place thereafter,[141] and there have been no recent sightings of the species in Korean waters.

Western gray whales are facing large-scale offshore oil and gas development programs near their summer feeding grounds, as well as fatal net entrapments off Japan during migration, which pose significant threats to the future survival of the population.

[56][175] Offshore gas and oil development in the Okhotsk Sea within 20 km (12 mi) of the primary feeding ground off northeast Sakhalin Island is of particular concern.

Physical habitat damage from drilling and dredging operations, combined with possible impacts of oil and chemical spills on benthic prey communities also warrants concern.

Some scientists suggest that the lack of sea ice has been preventing the fertilization of amphipods, a main source of food for gray whales, so that they have been hunting krill instead, which is far less nutritious.

A possible explanation for this phenomenon is that solar storms release a large amount of electromagnetic radiation, which disrupts Earth's magnetic field and/or the whale's ability to analyze it.