Griot

The griot is a repository of oral tradition and is often seen as a leader due to their position as an advisor to members of the royal family.

[2] In African languages, griots are referred to by a number of names: ߖߋ߬ߟߌ jèli[3] in northern Mande areas, jali in southern Mande areas, guewel in Wolof, kevel or kewel or okawul in Serer,[4][5] gawlo 𞤺𞤢𞤱𞤤𞤮 in Pulaar (Fula), iggawen in Hassaniyan[citation needed], arokin in Yoruba,[citation needed] and diari or gesere in Soninke.

[citation needed] The Manding term ߖߋߟߌߦߊ jeliya (meaning "musicianhood") sometimes refers to the knowledge of griots, indicating the hereditary nature of the class.

[citation needed] Today, the term and spelling "djali" is often preferred, as noted by American poet Amiri Baraka[7] and Congolese filmmaker Balufu Bakupa-Kanyinda.

A village griot would relate stories of topics including births, deaths, marriages, battles, hunts, affairs, and other life events.

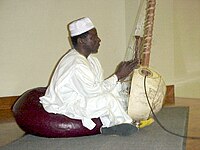

[11] Griots have the main responsibility for keeping stories of the individual tribes and families alive in the oral tradition, with the narrative accompanied by a musical instrument.

They are an essential part of many West African events such as weddings, where they sing and share family history of the bride and groom.

This virtuosity is the culmination of long years of study and hard work under the tuition of a teacher who is often a father or uncle.

There are many women griots whose talents as singers and musicians are equally remarkable.The Mali Empire (Malinke Empire), at its height in the middle of the 14th century, extended from central Africa (today's Chad and Niger) to West Africa (today's Mali, Burkina Faso and Senegal).

Thomas A. Hale wrote, "Another [reason for ambivalence towards griots] is an ancient tradition that marks them as a separate people categorized all too simplistically as members of a 'caste', a term that has come under increasing attack as a distortion of the social structure in the region.

In the worst case, that difference meant burial for griots in trees rather than in the ground in order to avoid polluting the earth (Conrad and Frank 1995:4-7).

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica: "West African plucked lutes such as the konting, khalam, and the nkoni (which was noted by Ibn Baṭṭūṭah in 1353) may have originated in ancient Egypt.

Many griots today live in many parts of West Africa and are present among the Mande peoples (Mandinka or Malinké, Bambara, Bwaba, Bobo, Dyula,Soninke etc.

), Fulɓe (Fula), Hausa, Songhai, Tukulóor, Wolof, Serer,[4][5] Mossi, Dagomba, Mauritanian Arabs[citation needed], and many other smaller groups.

Pape Demba "Paco" Samb, a Senegalese griot of Wolof ancestry, is based in Delaware and performs in the United States.

Though Diabaté argued that griots "no longer exist" in the classic sense, he believed the tradition could be salvaged through literature.