Hausa people

[16][17] The Hausa are a culturally homogeneous people based primarily in the Sahelian and the sparse savanna areas of southern Niger and northern Nigeria respectively,[18] numbering around 86 million people, with significant populations in Benin, Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Chad, Central African Republic, Togo, Ghana,[9] as well as smaller populations in Sudan, Eritrea,[11] Equatorial Guinea,[citation needed] Gabon, Senegal, Gambia.

Predominantly Hausa-speaking communities are scattered throughout West Africa and on the traditional Hajj route north and east traversing the Sahara, with an especially large population in and around the town of Agadez.

[19] Other Hausa have also moved to large coastal cities in the region such as Lagos, Port Harcourt, Accra, Abidjan, Banjul and Cotonou as well as to parts of North Africa such as Libya over the course of the last 500 years.

[30]The Hausa are culturally and historically closest to other Sahelian ethnic groups, primarily the Fula; the Zarma and Songhai (in Tillabery, Tahoua and Dosso in Niger); the Kanuri and Shuwa Arabs (in Chad, Sudan and northeastern Nigeria); the Tuareg (in Agadez, Maradi and Zinder); the Gur and Gonja (in northeastern Ghana, Burkina Faso, northern Togo and upper Benin); Gwari (in central Nigeria); and the Mandinka, Bambara, Dioula and Soninke (in Mali, Senegal, Gambia, Ivory Coast and Guinea).

"[32][33] In clear testimony to T. L Hodgkin's claim, the people of Agadez and Saharan areas of central Niger, the Tuareg and the Hausa groups are indistinguishable from each other in their traditional clothing; both wear the tagelmust and indigo Babban Riga/Gandora.

[37] However, the legend of Bayajidda is a relatively new concept in the history of the Hausa people that gained traction and official recognition under the Islamic government and institutions that were newly established after the 1804 Usman dan Fodio Jihad.

The mosque's origin is attributed to the efforts of the influential Islamic scholar Sheikh Muhammad al-Maghili and Sultan Muhammadu Korau of Katsina.

Amina was 16 years old when her mother, Bakwa Turunku became queen and she was given the traditional title of Magajiya, an honorific borne by the daughters of monarchs.

"[46] Amina is credited as the architectural overseer who created the strong earthen walls that surround her city, which were the prototype for the fortifications used in all Hausa states.

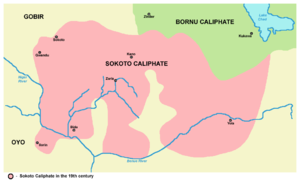

"[48]From 1804 to 1808, the Fulani, another Islamic African ethnic group that spanned West Africa and have settled in Hausaland since the early 1500s, with support of already oppressed Hausa peasants revolted against oppressive cattle tax and religious persecution under the new king of Gobir, whose predecessor and father had tolerated Muslim evangelists and even favoured the leading Muslim cleric of the day, Sheikh Usman Dan Fodio whose life the new king had sought to end.

[51] Lugard abolished the Caliphate, but retained the title Sultan as a symbolic position in the newly organised Northern Nigeria Protectorate.

[52] Following the construction of the Nigerian railway system, which extended from Lagos in 1896 to Ibadan in 1900 and Kano in 1911, the Hausa of northern Nigeria became major producers of groundnuts.

[67] In terms of overall ancestry, an autosomal DNA study by Tishkoff et al. (2009) found the Hausa to be most closely related to Nilo-Saharan populations from Chad and South Sudan.

These results are consistent with linguistic and archeological data, suggesting a possible common ancestry of Nilo-Saharan speaking populations from an eastern Sudanese homeland within the past ≈10,500 years, with subsequent bi-directional migration westward to Lake Chad and southward into modern day southern Sudan, and more recent migration eastward into Kenya and Tanzania ≈3,000 ya (giving rise to Southern Nilotic speakers) and westward into Chad ≈2,500 ya (giving rise to Central Sudanic speakers) (S62, S65, S67, S74).

A proposed migration of proto-Chadic Afroasiatic speakers ≈7,000 ya from the central Sahara into the Lake Chad Basin may have caused many western Nilo-Saharans to shift to Chadic languages (S99).

[citation needed] Consequently, and in spite of strong competition from western European culture as adopted by their southern Nigerian counterparts[citation needed], have maintained a rich and particular mode of dressing, food, language, marriage system, education system, traditional architecture, sports, music and other forms of traditional entertainment.

Hausa is also widely spoken in northern Ghana, Cameroon, Chad, and Ivory Coast as well as among Fulani, Tuareg, Kanuri, Gur, Shuwa Arab, and other Afro-Asiatic, Niger-Congo, and Nilo-Saharan speaking groups.

There is a large and growing printed literature in Hausa, which includes novels, poetry, plays, instruction in Islamic practice, books on development issues, newspapers, news magazines, and technical academic works.

Islam has been present in Hausaland since as early as the 11th century — giving rise to famous native Sufi saints and scholars such as Wali Muhammad dan Masani (d.1667) and Wali Muhammad dan Marina (d. 1655) in Katsina — mostly among long-distance traders to North Africa whom in turn had spread it to common people while the ruling class had remained largely pagan or mixed their practice of Islam with pagan practices.

Tie-dye techniques have been used in the Hausa region of West Africa for centuries with renowned indigo dye pits located in and around Kano, Nigeria.

Like other Muslims and specifically Sahelians within West Africa, Hausa women traditionally use Henna (lalle) designs painted onto the hand instead of nail-polish.

[86]The Hausa culture is rich in traditional sporting events such as boxing (Dambe), stick fight (Takkai), wrestling (Kokowa) etc.

[87] It originally started out among the lower class of Hausa butcher caste groups and later developed into a way of practicing military skills and then into sporting events through generations of Northern Nigerians.

A round ends if an opponent is knocked out, a fighter's knee, body or hand touch the ground, inactivity or halted by an official.

Dambe fighters may receive money, cattle, farm produce or jewelry as winnings but generally it was fought for fame from representations of towns and fighting clans.

[87] The most common food that the Hausa people prepare consists of grains, such as sorghum, millet, rice, or maize, which are ground into flour for a variety of different kinds of dishes.

The earliest Hausa Ajami manuscript with reliable date is the Ruwayar Annabi Musa by the Kano scholar Abdullah Suka, who lived in the 1600s.

[89] Other well-known scholars and saints of the Sufi order from Katsina, Danmarina and Danmasani have been composing Ajami and Arabic poetry from much earlier times also in the 1600s.

The subversive nature of these novels, which are often romantic and family dramas that are otherwise hard to find in the Hausa tradition and lifestyle, have made them popular, especially among female readers.

[2] An older and traditionally established emblem of Hausa identity, the 'Dagin Arewa' or Northern knot, in a star shape, is used in historic architecture, design and embroidery.