Hugo Grotius

He was imprisoned in Loevestein Castle for his involvement in the controversies over religious policy of the Dutch Republic, but escaped hidden in a chest of books that was regularly brought to him and was transported to Gorinchem.

"[8] Additionally, his contributions to Arminian theology helped provide the seeds for later Arminian-based movements, such as Methodism and Pentecostalism; Grotius is acknowledged as a significant figure in the Arminian–Calvinist debate.

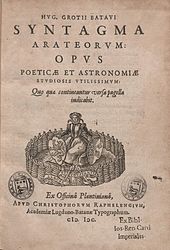

[13] At age 16 (1599), he published his first book: a scholarly edition of the late antique author Martianus Capella's work on the seven liberal arts, Martiani Minei Felicis Capellæ Carthaginiensis viri proconsularis Satyricon.

[16] The resulting work, entitled Annales et Historiae de rebus Belgicis, describing the period from 1559 to 1609, was written in the style of the Roman historian Tacitus[18] and was first finished in 1612.

[19] His first occasion to write systematically on issues of international justice came in 1604 when he became involved in the legal proceedings following the seizure by Dutch merchants of a Portuguese carrack and its cargo in the Singapore Strait.

Near the start of the war, Grotius's cousin captain Jacob van Heemskerk captured a loaded Portuguese carrack merchant ship, Santa Catarina, off present-day Singapore in 1603.

[21] Not only was the legality of keeping the prize questionable under Dutch statute, but a faction of shareholders (mostly Mennonite) in the Company also objected to the forceful seizure on moral grounds, and of course, the Portuguese demanded the return of their cargo.

Additionally, 16th-century Spanish theologian Francisco de Vitoria had postulated the idea of freedom of the seas in a more rudimentary fashion under the principles of jus gentium.

"[27] The domestic dissension resulting over Arminius' professorship was overshadowed by the continuing war with Spain, and the professor died in 1609 on the eve of the Twelve Years' Truce.

[citation needed] Grotius played a decisive part in this politico-religious conflict between the Remonstrants, supporters of religious tolerance, and the orthodox Calvinists or Counter-Remonstrants.

On the other side, Johannes Wtenbogaert (a Remonstrant leader) and Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, Grand Pensionary of Holland, had strongly promoted the appointment of Vorstius and began to defend their actions.

[citation needed] The Counter-Remonstrants were also supported in their opposition by King James I of England "who thundered loudly against the Leyden nomination and gaudily depicted Vorstius as a horrid heretic.

He ordered his books to be publicly burnt in London, Cambridge, and Oxford, and he exerted continual pressure through his ambassador in the Hague, Ralph Winwood, to get the appointment canceled.

Grotius (who acted during the controversy first as Attorney General of Holland and later as a member of the Committee of Counsellors) was eventually asked to draft an edict to express the policy of toleration.

The edict put into practice a view that Grotius had been developing in his writings on church and state (see Erastianism): that only the basic tenets necessary for undergirding civil order (e.g., the existence of God and His providence) ought to be enforced while differences on obscure theological doctrines should be left to private conscience.

[29] In early 1616, Grotius also received the 36-page letter championing a remonstrant view Dissertatio epistolica de Iure magistratus in rebus ecclesiasticis from his friend Gerardus Vossius.

[29] Around this time (April 1616) Grotius went to Amsterdam as part of his official duties, trying to persuade the civil authorities there to join Holland's majority view about church politics.

[33] From his imprisonment in Loevestein, Grotius made a written justification of his position "as to my views on the power of the Christian [civil] authorities in ecclesiastical matters, I refer to my...booklet De Pietate Ordinum Hollandiae and especially to an unpublished book De Imperio summarum potestatum circa sacra, where I have treated the matter in more detail...I may summarize my feelings thus: that the [civil] authorities should scrutinize God's Word so thoroughly as to be certain to impose nothing which is against it; if they act in this way, they shall in good conscience have control of the public churches and public worship – but without persecuting those who err from the right way.

While in Paris, Grotius set about rendering into Latin prose a work which he had originally written as Dutch verse in prison, providing rudimentary yet systematic arguments for the truth of Christianity.

The Dutch poem, Bewijs van den waren Godsdienst, was published in 1622, the Latin treatise in 1627, under the title De veritate religionis Christianae.

His most lasting work, begun in prison and published during his exile in Paris, was a monumental effort to restrain such conflicts on the basis of a broad moral consensus.

[37] De jure belli ac pacis libri tres (On the Law of War and Peace: Three books) was first published in 1625, dedicated to Grotius' current patron, Louis XIII.

The work is divided into three books: Grotius' concept of natural law had a strong impact on the philosophical and theological debates and political developments of the 17th and 18th centuries.

He washed up on the shore of Rostock, ill and weather-beaten, and on August 28, 1645, he died; his body at last returned to the country of his youth, being laid to rest in the Nieuwe Kerk in Delft.

[41][42] Grotius' personal motto was Ruit hora ("Time is running away"); his last words were purportedly, "By understanding many things, I have accomplished nothing" (Door veel te begrijpen, heb ik niets bereikt).

[43] Significant friends and acquaintances of his included the theologian Franciscus Junius, the poet Daniel Heinsius, the philologist Gerhard Johann Vossius, the historian Johannes Meursius, the engineer Simon Stevin, the historian Jacques Auguste de Thou, the Orientalist and Arabic scholar Erpinius, and the French ambassador in the Dutch Republic, Benjamin Aubery du Maurier, who allowed him to use the French diplomatic mail in the first years of his exile.

[46] Some philosophers, notably Protestants such as Pierre Bayle, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and the main representatives of the Scottish Enlightenment Francis Hutcheson, Adam Smith, David Hume, Thomas Reid held him in high esteem.

[46] Andrew Dickson White wrote: Into the very midst of all this welter of evil, at a point in time to all appearance hopeless, at a point in space apparently defenseless, in a nation of which every man, woman, and child was under sentence of death from its sovereign, was born a man who wrought as no other has ever done for the redemption of civilization from the main cause of all that misery; who thought out for Europe the precepts of right reason in international law; who made them heard; who gave a noble change to the course of human affairs; whose thoughts, reasonings, suggestions, and appeals produced an environment in which came an evolution of humanity that still continues.

[51] On the contrary, Schneewind argues that Grotius introduced the idea that "the conflict can not be eradicated and could not be dismissed, even in principle, by the most comprehensive metaphysical knowledge possible of how the world is made up".

See Catalogue of the Grotius Collection (Peace Palace Library, The Hague) and 'Grotius, Hugo' in Dictionary of Seventeenth Century Dutch Philosophers (Thoemmes Press 2003).