Group homomorphism

In mathematics, given two groups, (G,∗) and (H, ·), a group homomorphism from (G,∗) to (H, ·) is a function h : G → H such that for all u and v in G it holds that where the group operation on the left side of the equation is that of G and on the right side that of H. From this property, one can deduce that h maps the identity element eG of G to the identity element eH of H, and it also maps inverses to inverses in the sense that Hence one can say that h "is compatible with the group structure".

(or applying the cancellation rule) we obtain Similarly, Therefore for the uniqueness of the inverse:

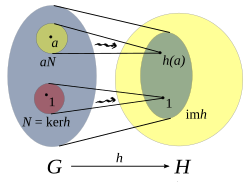

We define the kernel of h to be the set of elements in G which are mapped to the identity in H and the image of h to be The kernel and image of a homomorphism can be interpreted as measuring how close it is to being an isomorphism.

The first isomorphism theorem states that the image of a group homomorphism, h(G) is isomorphic to the quotient group G/ker h. The kernel of h is a normal subgroup of G. Assume

: The image of h is a subgroup of H. The homomorphism, h, is a group monomorphism; i.e., h is injective (one-to-one) if and only if ker(h) = {eG}.

Injection directly gives that there is a unique element in the kernel, and, conversely, a unique element in the kernel gives injection: forms a group under matrix multiplication.

The addition of homomorphisms is compatible with the composition of homomorphisms in the following sense: if f is in Hom(K, G), h, k are elements of Hom(G, H), and g is in Hom(H, L), then Since the composition is associative, this shows that the set End(G) of all endomorphisms of an abelian group forms a ring, the endomorphism ring of G. For example, the endomorphism ring of the abelian group consisting of the direct sum of m copies of Z/nZ is isomorphic to the ring of m-by-m matrices with entries in Z/nZ.