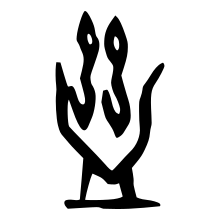

Gu (poison)

The traditional preparation of gu poison involved sealing several venomous creatures (e.g., centipede, snake, scorpion) inside a closed container, where they devoured one another and allegedly concentrated their toxins into a single survivor, whose body would be fed upon by larvae until consumed.

According to Chinese folklore, a gu spirit could transform into various animals, typically a worm, caterpillar, snake, frog, dog, or pig.

The term gu 蠱, says Loewe, "can be traced from the oracle bones until modern times, and has acquired a large number of meanings or connotations".

Carr proposes translating chong as "wug"[2] – Brown's portmanteau word (from worm + bug) bridging the lexical gap for the linguistically widespread "class of miscellaneous animals including insects, spiders, and small reptiles and amphibians".

153) connects gu, jincan, and other love charms with the Duanwu Festival that occurs on the fifth day of the fifth month in the Chinese calendar, which is "the theoretical apogee of summer heat".

[9] The Bencao Gangmu[10] quotes Cai Dao 蔡絛's (12th century) Tieweishan congtan 鐵圍山叢談 that "gold caterpillars first existed" in the Shu region (present-day Sichuan), and "only in recent times did they find their way into" Hubei, Hunan, Fujian, Guangdong, and Guanxi, Hsinchu.

... [Zhao Meng] (further) asked what he meant by 'insanity'; and (the physician) replied, "I mean that which is produced by the delusion and disorder of excessive sensual indulgence.

This specialized torture term niejie 臬磔 combines nie "target" (which pictures a person's 自 "nose" on a 木 "tree; wooden stand") and jie 磔 "dismemberment".

Compare the character for xian 縣 "county; district" that originated as a "place where dismembered criminals were publicly displayed" pictograph of an upside-down 首 "head" hanging on a 系 "rope" tied to a 木 "tree".

The primary host was considered a criminal; a person guilty of the despicable act of preparing and administering ku poison was executed, occasionally with his entire family, in a gruesome manner.

[19] The fourth meaning of "evil heat and noxious qi that harms humans" refers to allegedly sickness-causing emanations of tropical miasma.

"There was also an ancient belief that ku diseases were induced by some sort of noxious mist or exhalation", writes Schafer, "just as it was also believed that certain airs and winds could generate worms".

[20] The Shiji (秦本紀[21]) records that in 675 BCE, Duke De 德公 of Qin "suppressed ku at the commencement of the hottest summer-period by means of dogs.

The Tang dynasty commentary of Zhang Shoujie 張守節 explains gu as "hot, poisonous, evil, noxious qi that harms people".

And when my paternal uncle, on coming home, had a meal with Chao Sheu's wife, he spit blood, and was saved from death in the nick of time by a drink prepared from minced stalks of an orange-tree.

The Shanhaijing (山海经)[23] says the meat of a mythical creature on Mount Greenmound prevents miasmic gu poisoning, "There is an animal on this mountain that looks like a fox, but has nine tails.

A Tang dynasty account of Nanyue people[20] describes gu miasma: The majority are diseased, and ku forms in their bloated bellies.

The Hanshu provides details of wugu-sorcery scandals and dynastic rivalries in the court of Emperor Wu (r. 141–87 BCE), which Schafer calls "notorious dramas of love and death".

[25] This early Chinese history[26] records that in 130 BCE, a daughter of Empress Chen Jiao (who was unable to bear a son) was accused of practicing wugu and maigu 埋蠱 "bury a witchcraft charm [under a victim's path or dwelling]" (cf.

[17] Accusations of practicing wugu-magic were central to the 91 BCE (Wugu zhi huo 巫蠱之禍) attempted coup against crown prince Liu Ju by Jiang Chong 江充 and Su Wen 蘇文.

"Ku-poisoning was also associated with demoniac sexual appetite – an idea traceable back to Chou times", says Schafer, "This notion evidently had its origins in stories of ambiguous love potions prepared by the aboriginal women of the south".

[25] The Zuozhuan (莊公28)[28] uses gu in a story that in the 7th century BCE, Ziyuan 子元, the chief minister of Chu, "wished to seduce the widow" of his brother King Wen of Zhou.

In the Zuozhuan (僖公15),[35] divination of this Gu hexagram foretells Qin conquering Jin, "A lucky response; cross the Ho; the prince's chariots are defeated."

According to ancient gu traditions, explain Joseph Needham and Wang Ling, "the poison was prepared by placing many toxic insects in a closed vessel and allowing them to remain there until one had eaten all the rest – the toxin was then extracted from the survivor.

This was done by feeding it to unrelated persons who would either spit blood or whose stomachs would swell because of the food they had taken would become alive in their insides, and who would die as a result; similar to the gold-silkworms, their souls had to be servants of the owner of the ku.

[40] For instance (see 2.4), the Shanhaijing claimed eating a legendary creature's meat would prevent gu and the Soushenji prescribed ranghe 蘘荷 "myoga ginger".

[41] The Zhou houbei jifang 肘後備急方,[42] which is attributed to Ge Hong, describes gu diagnosis and cure with ranghe: A patient hurt by ku gets cutting pains at his heart and belly as if some living thing is gnawing there; sometimes he has a discharge of blood through the mouth or the anus.

Again place some jang-ho leaves secretly under the mattress of the patient; he will then of his own accord immediately mention the name of the owner of the kuMany gu-poison antidotes are homeopathic, in Western terms.

[36] Chen[44] further describes catching and preparing medicine from the shapeshifting gu creature that, … can conceal its form, and seem to be a ghost or spirit, and make misfortune for men.

[45] From descriptions of gu poisoning such involving "swollen abdomen, emaciation, and the presence of worms in the body orifices of the dead or living", Unschuld reasons, "Such symptoms allow a great number of possible explanations and interpretations".