Guido of Arezzo

[5] Burney furthered that, in the words of musicologist Samuel D. Miller, "Guido's modesty, selfless abandon from material gain life, and obedience to authority tended to obscure his moves, work, and motivations".

[6] These dubious claims include that he spent much of life in France (recorded as early as Johannes Trithemius's 1494 De scriptoribus ecclesiasticis); that he trained in the Saint-Maur-des-Fossés near Paris;[6] and unsupported rumours that he was imprisoned because of plots from those hostile to his innovations.

[7][n 2] These letters provide enough information and context to map the main events and chronology of Guido's life,[7] though Miller notes that they do "not permit a detailed, authoritative sketch".

[17] If Mafucci is correct, Guido would have received early musical education at the Arezzo Cathedral from a deacon named Sigizo and was ordained as a subdeacon and active as a cantor.

[18][n 7] "Guido [...] perhaps attracted by the fame of what was considered one of the most famous Benedictine abbeys, full of hope of new spiritual and musical life, he enters the monastery of Pomposa, unaware of the storm that, in a few years, it would hit him.

[1] Likely drawing from the writings of Odo of Saint-Maur-des-Fossés [sv],[1] Guido began to draft his system in the antiphonary Regulae rhythmicae, which he probably worked on with his colleague Michael of Pomposa.

[21] The system, he explained, would prevent the need for memorization and thus permit the singers extra time to diversify their studies into other prayers and religious texts.

[6] Italy-wide attention returned to Guido, and Pope John XIX called him to Rome, having either seen or heard of both his Regulae rhythmicae and innovative staff notation teaching techniques.

[6] While in Rome, Guido became sick and the hot summer forced him to leave, with the assurance that he would visit again and give further explanation of his theories.

[20] More specifically, the Micrologus can be dated to after 1026, as in the preliminary dedicatory letter to Tebald, Guido congratulates him for his 1026 plans for the new St Donatus church.

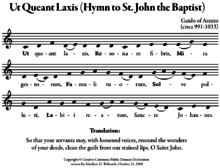

The syllables ut-re-mi-fa-sol-la (do-re-mi-fa-sol-la) are taken from the six half-lines of the first stanza of the hymn Ut queant laxis, the notes of which are successively raised by one step, and the text of which is attributed to the Italian monk and scholar Paulus Deacon (although the musical line either shares a common ancestor with the earlier setting of Horace's Ode to Phyllis (Odes 4.11) recorded in Montpellier manuscript H425, or may have been taken from there)[24] Giovanni Battista Doni is known for having changed the name of note "Ut" (C), renaming it "Do" (in the "Do Re Mi ..." sequence known as solfège).

[25] A seventh note, "Si" (from the initials for "Sancte Iohannes," Latin for Saint John the Baptist) was added shortly after to complete the diatonic scale.

Only a rudimentary form of the Guidonian hand is actually described by Guido, and the fully elaborated system of natural, hard, and soft hexachords cannot be securely attributed to him.

Guido of Arezzo's alleged development of the Guidonian hand, more than a hundred years after his death, allowed musicians to label a specific joint or fingertip with the gamut (also referred to as the hexachord in the modern era).

[29] The knowledge and use of the Guidonian hand would allow a musician to simply transpose, identify intervals, and aid in the use of notation and the creation of new music.

Musicians were able to sing and memorize longer sections of music and counterpoint during performances and the amount of time spent diminished dramatically.

Among these was a monograph competition; Jos Smits van Waesberghe won with the Latin work De musico-paedagogico et theoretico Guidone Aretino eiusque vita et moribus (The Musical-Pedagogy of Theoretician Guido of Arezzo Both His Life and Morals).