Gun-type fission weapon

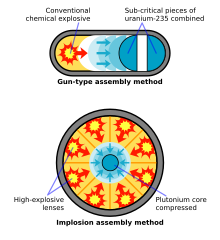

Although this is sometimes pictured as two sub-critical hemispheres driven together to make a supercritical sphere, typically a hollow projectile is shot onto a spike, which fills the hole in its center.

The main reason for this is the uranium metal does not undergo compression (and resulting density increase) as does the implosion design.

Instead, gun-type bombs assemble the supercritical mass by amassing such a large quantity of uranium that the overall distance through which daughter neutrons must travel has so many mean free paths it becomes very probable most neutrons will find uranium nuclei to collide with, before escaping the supercritical mass.

[3] The bomb would use the gun-type design "to bring the two halves together at high velocity and it is proposed to do this by firing them together with charges of ordinary explosive in a form of double gun".

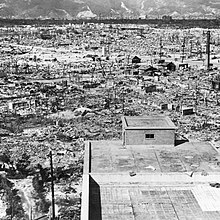

The "gun" method is roughly how the Little Boy weapon, which was detonated over Hiroshima, worked, using uranium-235 as its fissile material.

Its length was 70.8 inches (1.8 m), which allowed the bullet to accelerate to its final speed of about 1,000 feet per second (300 m/s)[5] before coming into contact with the target.

Typically the chain reaction takes less than 1 μs (100 shakes), during which time the bullet travels only 0.3 mm (1⁄85 inch).

Initially the Manhattan Project gun-type effort was directed at making a gun weapon that used plutonium as its source of fissile material, known as the "Thin Man" because of its extreme length.

Little Boy's target subcritical mass was enclosed in a neutron reflector made of tungsten carbide (WC).

A more effective reflector material would be metallic beryllium, but this was not known until the postwar years when Ted Taylor developed an implosion design known as "Scorpion".

With regard to the risk of proliferation and use by terrorists, the relatively simple design is a concern, as it does not require as much fine engineering or manufacturing as other methods.

With enough highly enriched uranium, nations or groups with relatively low levels of technological sophistication could create an inefficient—though still quite powerful—gun-type nuclear weapon.

For technologically advanced states the gun-type method is now essentially obsolete, for reasons of efficiency and safety (discussed above).

The gun type method was largely abandoned by the United States as soon as the implosion technique was perfected, though it was retained in the specialised role of nuclear artillery for a time.

The implosion technique is much better suited to the various methods employed to reduce the mass of the weapon and increase the proportion of material which fissions.

For example, it is inherently dangerous to have a weapon containing a quantity and shape of fissile material that can form a critical mass through a relatively simple accident.

Neither can happen with an implosion-type weapon, since there is normally insufficient fissile material to form a critical mass without the correct detonation of the explosive lenses.