Gyrocompass

A gyrocompass is a type of non-magnetic compass which is based on a fast-spinning disc and the rotation of the Earth (or another planetary body if used elsewhere in the universe) to find geographical direction automatically.

[4] This is because they have two significant advantages over magnetic compasses:[3] Aircraft commonly use gyroscopic instruments (but not a gyrocompass) for navigation and attitude monitoring; for details, see flight instruments (specifically the heading indicator) and gyroscopic autopilot.

The first, not yet practical,[5] form of gyrocompass was patented in 1885 by Marinus Gerardus van den Bos.

[5] A usable gyrocompass was invented in 1906 in Germany by Hermann Anschütz-Kaempfe, and after successful tests in 1908 became widely used in the German Imperial Navy.

[7] The gyrocompass was an important invention for nautical navigation because it allowed accurate determination of a vessel’s location at all times regardless of the vessel’s motion, the weather and the amount of steel used in the construction of the ship.

The unit was adopted by the U.S. Navy (1911[3]), and played a major role in World War I.

The Navy also began using Sperry's "Metal Mike": the first gyroscope-guided autopilot steering system.

In the following decades, these and other Sperry devices were adopted by steamships such as the RMS Queen Mary, airplanes, and the warships of World War II.

Meanwhile, in 1913, C. Plath (a Hamburg, Germany-based manufacturer of navigational equipment including sextants and magnetic compasses) developed the first gyrocompass to be installed on a commercial vessel.

By 1880, William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) tried to propose a gyrostat to the British Navy.

In 1889, Arthur Krebs adapted an electric motor to the Dumoulin-Froment marine gyroscope, for the French Navy.

That gave the Gymnote submarine the ability to keep a straight line while underwater for several hours, and it allowed her to force a naval block in 1890.

In 1923 Max Schuler published his paper containing his observation that if a gyrocompass possessed Schuler tuning such that it had an oscillation period of 84.4 minutes (which is the orbital period of a notional satellite orbiting around the Earth at sea level), then it could be rendered insensitive to lateral motion and maintain directional stability.

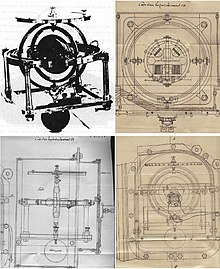

[10] A gyroscope, not to be confused with a gyrocompass, is a spinning wheel mounted on a set of gimbals so that its axis is free to orient itself in any way.

The crucial additional ingredient needed to turn a gyroscope into a gyrocompass, so it would automatically position to true north,[2][3] is some mechanism that results in an application of torque whenever the compass's axis is not pointing north.

One method uses friction to apply the needed torque:[8] the gyroscope in a gyrocompass is not completely free to reorient itself; if for instance a device connected to the axis is immersed in a viscous fluid, then that fluid will resist reorientation of the axis.

This friction force caused by the fluid results in a torque acting on the axis, causing the axis to turn in a direction orthogonal to the torque (that is, to precess) along a line of longitude.

Once the axis points toward the celestial pole, it will appear to be stationary and won't experience any more frictional forces.

This axis orientation is considered to be a point of minimum potential energy.

[2][3] In this case, gravity will apply a torque forcing the compass's axis toward true north.

Since the gyrocompass's north-seeking function depends on the rotation around the axis of the Earth that causes torque-induced gyroscopic precession, it will not orient itself correctly to true north if it is moved very fast in an east to west direction, thus negating the Earth's rotation.

These include steaming error, where rapid changes in course, speed and latitude cause deviation before the gyro can adjust itself.

[13] On most modern ships the GPS or other navigational aids feed data to the gyrocompass allowing a small computer to apply a correction.

In this case a non-rotating observer located at the center of the Earth can be approximated as being an inertial frame.

Consider another (non-inertial) observer (the 2-O) located at the center of the Earth but rotating about the NS-axis by

We now choose another coordinate basis whose origin is located at the barycenter of the gyroscope.

Since the height of the gyroscope's barycenter does not change (and the origin of the coordinate system is located at this same point), its gravitational potential energy is constant.

This simple solution implies that the gyroscope is uniformly rotating with constant angular velocity in both the vertical and symmetrical axis.

If this situation occurs, the gyroscope will always be approximately aligned along the north-south line, giving direction.

, where the angular velocity of this harmonic motion of the axis of symmetry of the gyrocompass about the north-south line is given by