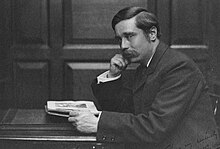

H. G. Wells

[1][2] In addition to his fame as a writer, he was prominent in his lifetime as a forward-looking, even prophetic social critic who devoted his literary talents to the development of a progressive vision on a global scale.

As a futurist, he wrote a number of utopian works[3] and foresaw the advent of aircraft, tanks, space travel, nuclear weapons, satellite television and something resembling the World Wide Web.

An inheritance had allowed the family to acquire a shop in which they sold china and sporting goods, although it failed to prosper in part because the stock was old and worn out, and the location was poor.

Joseph Wells managed to earn a meagre income, but little of it came from the shop and he received an unsteady amount of money from playing professional cricket for the Kent county team.

"[24] In October 1879, Wells's mother arranged through a distant relative, Arthur Williams, for him to join the National School at Wookey in Somerset as a pupil–teacher, a senior pupil who acted as a teacher of younger children.

In 1883, Wells persuaded his parents to release him from the apprenticeship, taking an opportunity offered by Midhurst Grammar School again to become a pupil–teacher; his proficiency in Latin and science during his earlier short stay had been remembered.

[17][21] The years he spent in Southsea had been the most miserable of his life to that point, but his good fortune in securing a position at Midhurst Grammar School meant that Wells could continue his self-education in earnest.

At first approaching the subject through Plato's Republic, he soon turned to contemporary ideas of socialism as expressed by the recently formed Fabian Society and free lectures delivered at Kelmscott House, the home of William Morris.

The inspiration for some of his descriptions in The War of the Worlds is thought to have come from his short time spent here, seeing the iron foundry furnaces burn over the city, shooting huge red light into the skies.

To earn money, he began writing short humorous articles for journals such as The Pall Mall Gazette, later collecting these in Select Conversations with an Uncle (1895) and Certain Personal Matters (1897).

[48] David Lodge's novel A Man of Parts (2011) – a 'narrative based on factual sources' (author's note) – gives a convincing and generally sympathetic account of Wells's relations with the women mentioned above, and others.

One common location for these was the endpapers and title pages of his own diaries, and they covered a wide variety of topics, from political commentary to his feelings toward his literary contemporaries and his current romantic interests.

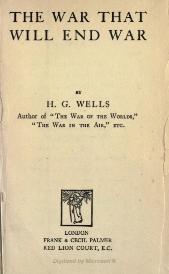

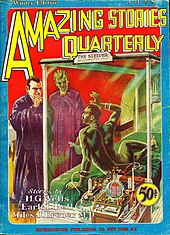

[51] Some of his early novels, called "scientific romances", invented several themes now classic in science fiction in such works as The Time Machine, The Island of Doctor Moreau, The Invisible Man, The War of the Worlds, When the Sleeper Wakes, and The First Men in the Moon.

Wells also wrote dozens of short stories and novellas, including, "The Flowering of the Strange Orchid", which helped bring the full impact of Darwin's revolutionary botanical ideas to a wider public, and was followed by many later successes such as "The Country of the Blind" (1904).

[64] In 1932, the physicist and conceiver of nuclear chain reaction Leó Szilárd read The World Set Free (the same year Sir James Chadwick discovered the neutron), a book which he wrote in his memoirs had made "a very great impression on me".

Anticipating what the world would be like in the year 2000, the book is interesting both for its hits (trains and cars resulting in the dispersion of populations from cities to suburbs; moral restrictions declining as men and women seek greater sexual freedom; the defeat of German militarism, and the existence of a European Union) and its misses (he did not expect successful aircraft before 1950, and averred that "my imagination refuses to see any sort of submarine doing anything but suffocate its crew and founder at sea").

Wells in this period was regarded as an enormously influential figure; the literary critic Malcolm Cowley stated: "by the time he was forty, his influence was wider than any other living English writer".

B. McKillop, a professor of history at Carleton University, produced a book on the case, The Spinster & The Prophet: Florence Deeks, H. G. Wells, and the Mystery of the Purloined Past.

[83] According to McKillop, the lawsuit was unsuccessful due to the prejudice against a woman suing a well-known and famous male author, and he paints a detailed story based on the circumstantial evidence of the case.

[98] On 23 July 1934, after visiting U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Wells went to the Soviet Union and interviewed Joseph Stalin for three hours for the New Statesman magazine, which was extremely rare at that time.

As the chairman of the London-based PEN International, which protected the rights of authors to write without being intimidated, Wells hoped by his trip to USSR, he could win Stalin over by force of argument.

"[108] Wells's body was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium on 16 August 1946; his ashes were subsequently scattered into the English Channel at Old Harry Rocks, the most eastern point of the Jurassic Coast and about 3.5 miles (5.6 km) from Swanage in Dorset.

[110] A futurist and "visionary", Wells foresaw the advent of aircraft, tanks, space travel, nuclear weapons, satellite television, and something resembling the World Wide Web.

[113] In a 2013 review of The Time Machine for the New Yorker magazine, Brad Leithauser writes, "At the base of Wells's great visionary exploit is this rational, ultimately scientific attempt to tease out the potential future consequences of present conditions—not as they might arise in a few years, or even decades, but millennia hence, epochs hence.

The writer suggested that the great outline of the theological struggles of that phase of civilisation and world unity which produced Christianity, was a persistent but unsuccessful attempt to get these two different ideas of God into one focus.

"[127] Wells's opposition to organised religion reached a fever pitch in 1943 with publication of his book Crux Ansata, subtitled "An Indictment of the Roman Catholic Church" in which he attacked Catholicism, Pope Pius XII and called for the bombing of the city of Rome.

[129] Science fiction author and critic Algis Budrys said Wells "remains the outstanding expositor of both the hope, and the despair, which are embodied in the technology and which are the major facts of life in our world".

In a six-year stretch from 1895 to 1901, he produced a stream of what he called "scientific romance" novels, which included The Time Machine, The Island of Doctor Moreau, The Invisible Man, The War of the Worlds and The First Men in the Moon.

[129] Later American writers such as Ray Bradbury,[142] Isaac Asimov,[143] Frank Herbert,[144] Carl Sagan,[131] and Ursula K. Le Guin[145] all recalled being influenced by Wells.

Late in his life, Borges included The Invisible Man and The Time Machine in his Prologue to a Personal Library,[150] a curated list of 100 great works of literature that he undertook at the behest of the Argentine publishing house Emecé.