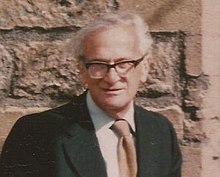

H. L. A. Hart

Born in Harrogate, England, Hart received a first class honours degree in classical studies from New College, Oxford, before qualifying at the English bar.

During World War II, Hart served in British intelligence, working with figures such as Alan Turing and Dick White.

Hart's influence extended beyond his own work, mentoring legal thinkers the likes of Joseph Raz, John Finnis, Ronald Dworkin.

He received a Harmsworth Scholarship to the Middle Temple and also wrote literary journalism for the periodical John O'London's Weekly.

[7] Hart's war work took him on occasion to MI5 offices at Blenheim Palace, family home of the Dukes of Marlborough and the place where Winston Churchill had been born.

Another incident at Blenheim that Hart enjoyed recounting was that he shared an office with one of the famous Cambridge spies, Anthony Blunt, a fellow member of MI5.

Hart did not return to his legal practice after the war, preferring instead to accept the offer of a teaching fellowship (in philosophy, not law) at New College, Oxford.

[10] Jenifer Hart was, for some years in the mid-1930s and fading out totally by decade's end, a 'sleeper' member of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

Nor was her husband in a position to convey to her information of use, despite vague newspaper suggestions, given the sharp separation of his work from that of foreign affairs and its focus on German spies and British turncoats rather than on matters related to the Soviet ally.

The Harts had four children, including, late in life, a son who was disabled, the umbilical cord wrapped around his neck having deprived his brain of oxygen.

[14] There is a description of the Harts' household by the writer on religion Karen Armstrong, who lodged with them for a time to help take care of their disabled son.

Many of Hart's former students have become important legal, moral, and political philosophers, including Brian Barry, Ronald Dworkin, John Finnis, John Gardner, Kent Greenawalt, Peter Hacker, David Hodgson, Neil MacCormick, Joseph Raz, Chin Liew Ten and William Twining.

Influenced by John Austin, Ludwig Wittgenstein and Hans Kelsen, Hart brought the tools of analytic, and especially linguistic, philosophy to bear on the central problems of legal theory.

Hart's method combined the careful analysis of twentieth-century analytic philosophy with the jurisprudential tradition of Jeremy Bentham, the great English legal, political, and moral philosopher.

They had been wasting everyone's time, for the question was not a factual one, the many differences between municipal and international law being undeniable, but was simply one of conventional verbal usage, about which individual theorists could please themselves, but had no right to dictate to others.