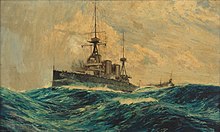

HMAS Australia (1911)

[23] Attitudes on this matter softened during the first decade, and at the 1909 Imperial Conference, the Admiralty proposed the creation of 'Fleet Units': forces consisting of a battlecruiser, three light cruisers, six destroyers, and three submarines.

[6][27] On 9 December 1909, a cable was sent by Governor-General Lord Dudley to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, The Earl of Crewe, requesting that construction of three Town class cruisers and an Indefatigable-class battlecruiser start at earliest opportunity.

[38] Australia and Sydney reached Jervis Bay on 2 October, where they rendezvoused with the rest of the RAN fleet (the cruisers Encounter and Melbourne, and the destroyers Parramatta, Warrego, and Yarra).

[69] The presence of Australia around the former German colonies, combined with the likelihood of Japan declaring war on Germany, prompted von Spee to withdraw his ships from the region.

[72] On 1 October, Australia, Sydney, Montcalm, and Encounter headed north from Rabaul to find the German ships, but turned around to return at midnight, after receiving an Admiralty message about the Tahiti attack.

[73] Although Patey suspected that the Germans were heading for South America and wanted to follow with Australia, the Admiralty was unsure that the intelligence was accurate, and tasked the battlecruiser with patrolling around Fiji in case they returned.

[74] As Patey predicted, von Spee had continued east, and it was not until his force inflicted the first defeat on the Royal Navy in 100 years at the Battle of Coronel that Australia was allowed to pursue.

[76] After finding no trace of von Spee's force, the Admiralty ordered Patey to investigate the South American coast from Perlas Island down to the Gulf of Guayaquil.

[59][78] Initially, the battlecruiser was to serve as flagship of the West Indies Squadron, with the task of pursuing and destroying any German vessels that evaded North Sea blockades.

[77][82] Unable to close the gap before sunset, a warning shot was fired from 'A' turret, which caused the ship—the former German passenger liner, now naval auxiliary Eleonora Woermann—to stop and be captured.

[85] During her time with the 2nd BCS, Australia's operations primarily consisted of training exercises (either in isolation or with other ships), patrols of the North Sea area in response to actual or perceived German movements, and some escort work.

[91] Heavy fog and the need to refuel caused Australia and the British vessels to return to port on 17 August, and although they were redeployed that night, they were unable to stop two German light cruisers from laying the minefield.

[93] On the morning of 21 April 1916, the 2nd BCS left Rosyth at 04:00 (accompanied by the 4th Light Cruiser Squadron and destroyers) again bound for the Skagerrak, this time to support efforts to disrupt the transport of Swedish ore to Germany.

[96] At 15:30 on the afternoon of 22 April, the three squadrons of battlecruisers were patrolling together to the north-west of Horn Reefs when heavy fog came down, while the ships were steaming abreast at 19.5 knots, with Australia on the port flank.

Once it was safe to proceed Australia with her speed restricted to 12, and then later to 16 knots lagging behind the rest of the squadron, arrived back at Rosyth at 16:00 hours on the 23 April to find both drydocks occupied, one by New Zealand and the other by HMS Dreadnought so she departed at 21:00 hours on that same day for Newcastle-on-Tyne, where as she approached its floating dock[97] on the River Tyne, on the 24 April the tugs were unable to keep her straight during strong winds and she hit the edge of the floating dock severely bending her port rudder and breaking both of her port propellers.

[111] Although many aboard Australia volunteered their services in an attempt to escape the drudgery of North Sea patrols, only 11 personnel—10 sailors and an artificer engineer were selected for the raid, which occurred on 23 April.

Factors which contributed to low morale and poor discipline included frustration at not participating in the Battle of Jutland, high rates of illness, limited opportunities for leave, delays or complete lack of deferred pay, and poor-quality food.

Stevens states that Cumberledge assembled the ship's company in the early afternoon, read the Articles of War, lectured them on the seriousness of refusing duty, then ordered the stokers to go to their stations, which they did meekly.

[135] Five men, including one of the Victoria Cross nominees from the Zeebrugge raid, were charged[F] with inciting a mutiny and arrested pending a court-martial, which was held aboard HMAS Encounter on 20 June, after Australia arrived in Sydney.

[140][141] Following the court-martial of the five ringleaders, there was debate among the public, in the media, and within government over the sentences; while most agreed that a mutiny had occurred, there were differences in opinion on the leniency or severity of the punishments imposed.

[125][146] The two officers were later convinced to withdraw their resignations after receiving assurances that Board would be consulted before all future government communications to Britain regarding the RAN, and that notices would be posted in all ships explaining that the sentences were correct, but the onset of peace had led to clemency in this particular case.

[149] From July to November 1920, an Avro 504 floatplane of the Australian Air Corps was embarked aboard Australia as part of a series of trials intended to cumulate in the creation of a naval aviation branch.

[2] The battlecruiser had to be made unusable for warlike activities within six months of the treaty's ratification, then disposed of by scuttling, as Australia did not have the facilities to break her up for scrap, and the British share of target ships was taken up by Royal Navy vessels.

[158] Some consideration was given to reusing Australia's 12-inch guns in coastal fortifications, but this did not occur as ammunition for these weapons was no longer being manufactured by the British, and the cost of building suitable structures was excessive.

[159] The former flagship was escorted by the Australian warships Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide, Anzac, and Stalwart, the ships of the Special Service Squadron, and several civilian ferries carrying passengers.

[166] The angle of list increased significantly, causing the three spare 12-inch barrels lashed to the deck to break free and roll overboard, before Australia inverted completely and began to sink stern-first.

[153][168] To remain effective, Australia required major modernisation (including new propulsion machinery, increased armour and armament, and new fire control systems) at a cost equivalent to a new County-class cruiser.

[170] One of the survey ship's crew theorised that the wreck, located at 33°51′54.21″S 151°44′25.11″E / 33.8650583°S 151.7403083°E / -33.8650583; 151.7403083 in 390 metres (1,280 ft) of water, was Australia, but Fugro kept the information to themselves until 2002, when the company's Australian branch mentioned the discovery during a conference.

[171] While en route back to Australia, the ROV, carried aboard Defence Maritime Services vessel Seahorse Standard, was directed to Fugro's coordinates at the request of the NSW Heritage Office to verify and inspect the wreck.

[171][172] Video footage captured by the ROV allowed the NSW Heritage Office to confirm that the wreck was Australia by matching features like the superstructure and masts to historical photographs.