Habeas Corpus Suspension Act (1863)

It began in the House of Representatives as an indemnity bill, introduced on December 5, 1862, releasing the president and his subordinates from any liability for having suspended habeas corpus without congressional approval.

[1] The Senate amended the House's bill,[2] and the compromise reported out of the conference committee altered it to qualify the indemnity and to suspend habeas corpus on Congress's own authority.

At the outbreak of the American Civil War in April 1861, Washington, D.C. was largely undefended, rioters in Baltimore, Maryland threatened to disrupt the reinforcement of the capital by rail, and Congress was not in session.

[5] In that same month (April 1861), Abraham Lincoln, the president of the United States, therefore authorized his military commanders to suspend the writ of habeas corpus between Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia (and later up through New York City).

When Judge William Fell Giles of the United States District Court for the District of Maryland issued a writ of habeas corpus, the commander of Fort McHenry, Major W. W. Morris, wrote in reply, "At the date of issuing your writ, and for two weeks previous, the city in which you live, and where your court has been held, was entirely under the control of revolutionary authorities.

"[8] Merryman's lawyers appealed, and in early June 1861, U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney, writing as the United States Circuit Court for Maryland, ruled in ex parte Merryman that Article I, section 9 of the United States Constitution reserves to Congress the power to suspend habeas corpus and thus that the president's suspension was invalid.

[12][13] Early in the session, Senator Henry Wilson introduced a joint resolution "to approve and confirm certain acts of the President of the United States, for suppressing insurrection and rebellion", including the suspension of habeas corpus (S. No.

On July 17, 1861, Trumbull introduced a bill to suppress insurrection and sedition which included a suspension of the writ of habeas corpus upon Congress's authority (S. 33).

On February 14, he ordered all political prisoners released, with some exceptions (such as the aforementioned newspaper editor) and offered them amnesty for past treason or disloyalty, so long as they did not aid the Confederacy.

[22] In September, faced with opposition to his calling up of the militia, Lincoln again suspended habeas corpus, this time through the entire country, and made anyone charged with interfering with the draft, discouraging enlistments, or aiding the Confederacy subject to martial law.

[23] In the interim, the controversy continued with several calls made for prosecution of those who acted under Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus; former Secretary of War Simon Cameron had even been arrested in connection with a suit for trespass vi et armis, assault and battery, and false imprisonment.

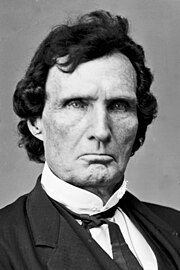

"[25] When the Thirty-seventh Congress of the United States opened its third session in December 1862, Representative Thaddeus Stevens introduced a bill "to indemnify the President and other persons for suspending the writ of habeas corpus, and acts done in pursuance thereof" (H.R.

First James Walter Wall of New Jersey spoke until midnight, when Willard Saulsbury, Sr., of Delaware gave Republicans an opportunity to surrender by moving to adjourn.

During the ensuing discussion, the president pro tempore asked permission "to sign a large number of enrolled bills", among which was the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act.

[36] The Act also provided for the release of prisoners in a section originally authored by Maryland Congressman Henry May, who had been arrested without recourse to habeas in 1861, while serving in Congress.

[38] If a grand jury failed to indict anyone on the list before the end of its session, that prisoner was to be released, so long as they took an oath of allegiance and swore that they would not aid the rebellion.

[42] President Lincoln used the authority granted him under the Act on September 15, 1863, to suspend habeas corpus throughout the Union in any case involving prisoners of war, spies, traitors, or any member of the military.

[45] Andrew Johnson restored civilian courts to Kentucky in October, 1865,[46] and revoked the suspension of habeas corpus in states and territories that had not joined the rebellion on December 1 later that year.

[49] The Court had earlier avoided the questions arising in ex parte Milligan regarding the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act in a case concerning former Congressman and Ohio Copperhead politician Clement Vallandigham.

The Supreme Court did not address the substance of Vallandigham's appeal, instead denying that it possessed the jurisdiction to review the proceedings of military tribunals upon a writ of habeas corpus without explicit congressional authorization.

[51] Mary Elizabeth Jenkins Surratt (May 1823 – July 7, 1865) was an American boarding house owner who was convicted of taking part in the conspiracy to assassinate President Abraham Lincoln.

[52][53] The provisions for the release of prisoners were incorporated into the Civil Rights Act of 1871, which authorized the suspension of habeas corpus in order to break the Ku Klux Klan.