Ethiopian Empire

While initially a rather small and politically unstable entity, the Empire managed to expand significantly under the crusades of Amda Seyon I (1314–1344) and Dawit I (1382–1413), temporarily becoming the dominant force in the Horn of Africa.

He consolidated the conquests of his predecessors, built numerous churches and monasteries, encouraged literature and art, centralized imperial authority by substituting regional warlords with administrative officials, and significantly expanded his hegemony over adjacent Islamic territories.

[25] Emperor Tewodros II (r. 1855–1868) put an end to the Zemene Mesafint, reunified the Empire and led it into the modern period before dying during the British Expedition to Abyssinia.

Through a resounding victory over the Italians at the Battle of Adwa in 1896, utilizing modern imported weaponry, Menelik ensured Ethiopia's independence and confined Italy to Eritrea.

[28] A more recent chronicler of Wollo history, Getatchew Mekonnen Hasen, states that the last Zagwe king deposed by Yekuno Amlak was Na'akueto La'ab.

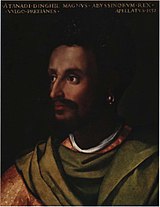

[34] Wedem Arad was succeeded by his son, Amda Seyon I, whose reign witnessed the composition of a very detailed and seemingly accurate account of the monarch's various campaigns against his Muslim enemies.

The Egyptian sultan then had the Patraich of Alexandria severely beaten and threaten to execute him, Emperor Zara Yaqob decided to back down and did not move in to Adal territory.

The Emperor did not hesitate to take the offensive and won a major victory at the Battle of Wayna Daga when the fate of Abyssinia was decided by the death of the Imam and the flight of his army.

The invasion force collapsed and all the Abyssinians who had been cowed by the invaders returned to their former allegiance, the reconquest of Christian territories proceeded without encountering any effective opposition.

This period saw profound achievements in Ethiopian art, architecture, and innovations such as the construction of the royal complex Fasil Ghebbi, and 44 churches[52] that were established around Lake Tana.

This was a period of Ethiopian history with numerous conflicts between the various Ras (equivalent to the English dukes) and the Emperor, who had only limited power and only dominated the area around the contemporary capital of Gondar.

As a result, the Treaty of Addis Ababa was signed in October, which strictly delineated the borders of Eritrea and forced Italy to recognize the independence of Ethiopia.

Beginning in the 1890s, under the reign of the Emperor Menelik II, the empire's forces set off from the central province of Shewa to incorporate through conquest inhabited lands to the west, east and south of its realm.

On May 1, 1936, Haile Selassie took a train to Djibouti and then boarded a British ship to Jerusalem,[60] spending the majority of his time in the city with Ethiopian monks, praying with them at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

The British accompanied Haile Selassie to Sudan and helped him organise his army within seven months,[67] finally launching a military campaign in January 1941 which returned him to the throne on May 5 of the same year.

[73] Ethiopia was still "semi-feudal",[74] and the emperor's attempts to alter its social and economic form by reforming its modes of taxation met with resistance from the nobility and clergy, which were eager to resume their privileges in the postwar era.

Haile Selassie applied to Egypt's Holy Synod in 1942 and 1945 to establish the independence of Ethiopian bishops, and when his appeals were denied he threatened to sever relations with the See of St.

[73] In addition to these efforts, Haile Selassie changed the Ethiopian church-state relationship by introducing taxation of church lands, and by restricting the legal privileges of the clergy, who had formerly been tried in their own courts for civil offenses.

[73][76] During the celebrations of his Silver Jubilee in November 1955, Haile Selassie introduced a revised constitution,[77] whereby he retained effective power, while extending political participation to the people by allowing the lower house of parliament to become an elected body.

The coup attempt lacked broad popular support, was denounced by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, and was unpopular with the army, air force and police.

Along with Modibo Keïta of Mali, the Ethiopian leader would later help successfully negotiate the Bamako Accords, which brought an end to the border conflict between Morocco and Algeria.

Marxism took root in large segments of the Ethiopian intelligentsia, particularly among those who had studied abroad and had thus been exposed to radical and left-wing sentiments that were becoming popular in other parts of the globe.

As these issues began to pile up, Haile Selassie left much of domestic governance to his Prime Minister, Aklilu Habte Wold, and concentrated more on foreign affairs.

The government's failure to adequately respond to the 1973 Wollo famine, the growing discontent of urban interest groups, and high fuel prices due to the 1973 oil crisis led to a revolt in February 1974 by the army and civilian populace.

In June, a group of military officers formed the Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces, Police, and Territorial Army also known as the Derg to maintain law and order due to the powerlessness of the civilian government following the widespread mutiny.

Soon both former Prime Ministers Tsehafi Taezaz Aklilu Habte-Wold and Endelkachew Makonnen, along with most of their cabinets, most regional governors, many senior military officers and officials of the Imperial court were imprisoned.

The Derg deposed and imprisoned the Emperor on 12 September 1974 and chose Lieutenant General Aman Andom, a popular military leader and a Sandhurst graduate, to be acting head of state.

However, General Aman Andom quarrelled with the radical elements in the Derg over the issue of a new military offensive in Eritrea and their proposal to execute the high officials of Selassie's former government.

These social groups consisted of the monks; the debtera; lay officials (including judges); men at arms giving personal protection to the wives of dignitaries and to princesses; the shimaglle, who were the lords and hereditary landowners; their farm labourers or serfs; traders; artisans; wandering singers; and the soldiers, who were called chewa.

The most common currency of the earlier periods of Ethiopian history were essential items such as, "amole" (salt bars), pieces of cloth or iron and later cartridges.