Waqf

[2] A waqf allows the state to provide social services in accordance with Islamic law while contributing to the preservation of cultural and historical sites.

In Sunni jurisprudence, waqf, also spelled wakf (Arabic: وَقْف; plural أَوْقاف, awqāf; Turkish: vakıf)[4] is synonymous with ḥabs (حَبْس, also called ḥubs حُبْس or ḥubus حُبْوس and commonly rendered habous in French).

A 'movable' asset includes money or shares which are used to finance educational, religious or cultural institutions such as madrasahs (Islamic schools) or mosques.

), land, and baths; and waqf, in its narrow sense, is the institution(s) providing services as committed in the vakıf deed, such as madrasas, public kitchens (imarets), karwansarays, mosques, libraries, etc.

[19] Out of 30,000 waqf certificates documented by the GDPFA (General Directorate of Pious Foundation in Ankara), over 2,300 of them were registered to institutions that belonged to women.

Whatever the declaration, most scholars (those of the Hanafi, Shafi'i, some of the Hanbali and the Imami Shi'a schools) hold that it is not binding and irrevocable until actually delivered to the beneficiaries or put to their use.

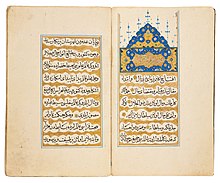

The oldest dated waqfiya goes back to 876 CE and concerns a multi-volume edition of the Qur'an currently held by the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum in Istanbul.

[25] A possibly older waqfiya is a papyrus held by the Louvre Museum in Paris, with no written date but considered to be from the mid-9th century.

The next oldest document is a marble tablet whose inscription bears the Islamic date equivalent to 913 CE and states the waqf status of an inn, but is in itself not the original deed; it is held at the Eretz Israel Museum in Tel Aviv.

Waqfization aimed [...] to control sources of revenue in a time of property confiscation and socio- economic upheavals and political insecurities.

According to Islamic law, only an owner (mallāk) can dedicate properties as waqf, therefore necessitating the production, confirmation and dissemination of official legal deeds which document the process [...].

[13] For several centuries, the income generated by these businesses contributed in the maintenance of a mosque, a soup kitchen, and two traveler and pilgrim inns.

The earliest known waqf, founded by financial official Abū Bakr Muḥammad bin Ali al-Madhara'i in 919 (during the Abbasid period), is a pond called Birkat Ḥabash together with its surrounding orchards, whose revenue was to be used to operate a hydraulic complex and feed the poor.

According to the book, Muhammad of Ghor dedicated two villages in favor of a congregational mosque in Multan, and, handed its administration to the Shaykh al-Islām (highest ecclesiastical officer of the Empire).

[35] Until this point, archeological evidence has unearthed several old mosques along the Swahili Coast which are believed to be informal waqf dating as far back as the 8th Century.

This marked a shift from waqf as an Islamic scriptural imperative to a local and centralized institutional practice legitimated by the royal family.

From this point onward, the urban development of the port city of the East African archipelago was shaped by waqf practices.

As such, the majority of greater Stone Town became waqf property made available for free habitation or cemeteries by noblemen, approximately 6.4% of which was public housing for the poor.

[37] In the context of growing inequality, the nobility used waqf to provide public housing to slaves and peasants as well mosques, madrasahs and land for free habitation and cultivation.

For instance, all 66 mosques in Stone Town were waqf privately financed and owned by noble waqif as a display of social status and duty to their neighborhood.

[41] This shift marked the further formalization of waqf into the state apparatus, a move which allowed the English to directly control the preservation and maintenance of publicly used assets as well as the surplus revenues generated from them.

It was also part of what Ali Mazrui calls the 'dis-Islamization' and 'de-Arabization' of Swahili culture by British colonialism, a strategy used to rid the territory of Omani influence.

[43] This ruptured the social and political relations that were formed between the upper and lower classes during Omani rule as the underlying values used to manage waqf were lost in translation.

This left a significant portion of land, much of which was waqf, to be nationalised by the newly independent state as part of their socialist development programme.

It allowed the poorest inhabitants of Stone Town to reside in waqf buildings that were previously reserved for the relatives of waqif families.

[46] While Bowen analyzes how Islamic rituals are practiced in context, this logic can arguably be applied to how the history of waqf in Zanzibar is shaped by "local cultural concerns and to universalistic scriptural imperatives".

Under Omani rule, waqf was practiced by the aristocratic class as an outward demonstration of Islamic piety while simultaneously serving as a means to control slaves and the local population through social housing, educational facilities and religious institutions like mosques.

After the British gained control of Zanzibar and further formalized waqf as a political institution, it was used to culturally subvert the local population and gradually rid it off its Arabic origins.

[55] Under both a waqf and a trust, "property is reserved, and its usufruct appropriated, for the benefit of specific individuals, or for a general charitable purpose; the corpus becomes inalienable; estates for life in favor of successive beneficiaries can be created" and "without regard to the law of inheritance or the rights of the heirs; and continuity is secured by the successive appointment of trustees or mutawillis.

The Court of Chancery, under the principles of equity, enforced the rights of absentee Crusaders who had made temporary assignments of their lands to caretakers.