Geography and cartography in the medieval Islamic world

Muslim scholars made advances to the map-making traditions of earlier cultures,[1] explorers and merchants learned in their travels across the Old World (Afro-Eurasia).

[1] Various Islamic scholars contributed to the development of geography and cartography, with the most notable including Al-Khwārizmī, Abū Zayd al-Balkhī (founder of the "Balkhi school"), Al-Masudi, Abu Rayhan Biruni and Muhammad al-Idrisi.

[10] Unlike the Balkhi school, geographers of the Khordadbeh–Jayhani tradition sought to describe the whole world as they knew it, including the lands, societies and cultures of non-Muslims.

[13] Balkhi and his followers reoriented geographic knowledge in order to bring it in line with certain concepts found in the Quran, emphasised the central importance of Mecca and Arabia, and ignored the non-Islamic world.

It is a revised and completed version of Ptolemy's Geography, consisting of a list of 2402 coordinates of cities and other geographical features following a general introduction.

[4]: 188 Other prime meridians used were set by Abū Muhammad al-Hasan al-Hamdānī and Habash al-Hasib al-Marwazi at Ujjain, a centre of Indian astronomy, and by another anonymous writer at Basra.

[22] The Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi produced his medieval atlas, Tabula Rogeriana or The Recreation for Him Who Wishes to Travel Through the Countries, in 1154.

He incorporated the knowledge of Africa, the Indian Ocean and the Far East gathered by Arab merchants and explorers with the information inherited from the classical geographers to create the most accurate map of the world in pre-modern times.

[23] With funding from Roger II of Sicily (1097–1154), al-Idrisi drew on the knowledge collected at the University of Córdoba and paid draftsmen to make journeys and map their routes.

The relative position of the lakes which form the Nile, as delineated in his work, does not differ greatly from that established by Baker and Stanley more than seven hundred years afterwards, and their number is the same.

The celestial and terrestrial planisphere of silver which he constructed for his royal patron was nearly six feet in diameter, and weighed four hundred and fifty pounds; upon the one side the zodiac and the constellations, upon the other—divided for convenience into segments—the bodies of land and water, with the respective situations of the various countries, were engraved.Al-Idrisi's atlas, originally called the Nuzhat in Arabic, served as a major tool for Italian, Dutch and French mapmakers from the 16th century to the 18th century.

[3] The earliest surviving rectangular coordinate map is dated to the 13th century and is attributed to Hamdallah al-Mustaqfi al-Qazwini, who based it on the work of Suhrāb.

The earliest surviving world maps based on a rectangular coordinate grid are attributed to al-Mustawfi in the 14th or 15th century (who used invervals of ten degrees for the lines), and to Hafiz-i Abru (died 1430).

wrote "Rihlah" (Travels) based on three decades of journeys, covering more than 120,000 km through northern Africa, southern Europe, and much of Asia.

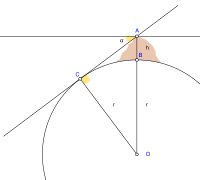

[1] Astrolabes were adopted and further developed in the medieval Islamic world, where Muslim astronomers introduced angular scales to the design,[28] adding circles indicating azimuths on the horizon.

[30] The mathematical background was established by Muslim astronomer Albatenius in his treatise Kitab az-Zij (c. 920 AD), which was translated into Latin by Plato Tiburtinus (De Motu Stellarum).

In the Islamic world, astrolabes were used to find the times of sunrise and the rising of fixed stars, to help schedule morning prayers (salat).

In the 10th century, al-Sufi first described over 1,000 different uses of an astrolabe, in areas as diverse as astronomy, astrology, navigation, surveying, timekeeping, prayer, Salat, Qibla, etc.

[37] The earliest Arabic reference to a compass, in the form of magnetic needle in a bowl of water, comes from a work by Baylak al-Qibjāqī, written in 1282 while in Cairo.

[34] Since the author describes having witnessed the use of a compass on a ship trip some forty years earlier, some scholars are inclined to antedate its first appearance in the Arab world accordingly.

[39] Late in the 13th century, the Yemeni Sultan and astronomer al-Malik al-Ashraf described the use of the compass as a "Qibla indicator" to find the direction to Mecca.

One instrument is a "fish" made of willow wood or pumpkin, into which a magnetic needle is inserted and sealed with tar or wax to prevent the penetration of water.

[44] However, Needham described this theory as "erroneous" and "it originates because of a mistranslation" of the term chia-ling found in Zhu Yu's book Pingchow Table Talks.