Hadley cell

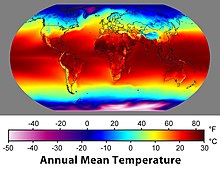

The Hadley circulation is also a key mechanism for the meridional transport of heat, angular momentum, and moisture, contributing to the subtropical jet stream, the moist tropics, and maintaining a global thermal equilibrium.

The existence of a broad meridional circulation of the type suggested by Hadley was confirmed in the mid-20th century once routine observations of the upper troposphere became available via radiosondes.

The broad ascent and descent of air results in a pressure gradient force that drives the Hadley circulation and other large-scale flows in both the atmosphere and the ocean, distributing heat and maintaining a global long-term and subseasonal thermal equilibrium.

Hadley cell intensity can also be assessed using other physical quantities such as the velocity potential, vertical component of wind, transport of water vapor, or total energy of the circulation.

[27][28] Considering only the conservation of angular momentum, a parcel of air at rest along the equator would accelerate to a zonal speed of 134 m/s (480 km/h; 300 mph) by the time it reached 30° latitude.

[38] The intensification of the winter hemisphere's cell is associated with a steepening of gradients in geopotential height, leading to an acceleration of trade winds and stronger meridional flows.

[45] During El Niño, the Hadley circulation strengthens due to the increased warmth of the upper troposphere over the tropical Pacific and the resultant intensification of poleward flow.

However, as parcels of air move equatorward in the cell's upper branch, they lose entropy by radiating heat to space at infrared wavelengths and descend in response.

[72] In 1685, English polymath Edmund Halley proposed at a debate organized by the Royal Society that the trade winds resulted from east to west temperature differences produced over the course of a day within the tropics.

[72] Halley conceded in personal correspondence with John Wallis that "Your questioning my hypothesis for solving the Trade Winds makes me less confident of the truth thereof".

[74] Nonetheless, Halley's formulation was incorporated into Chambers's Encyclopaedia and La Grande Encyclopédie, becoming the most widely-known explanation for the trade winds until the early 19th century.

[76] Hadley's explanation implied the existence of hemisphere-spanning circulation cells in the northern and southern hemispheres extending from the equator to the poles,[78] though he relied on an idealization of Earth's atmosphere that lacked seasonality or the asymmetries of the oceans and continents.

[88] The work of Gustave Coriolis, William Ferrel, Jean Bernard Foucault, and Henrik Mohn in the 19th century helped establish the Coriolis force as the mechanism for the deflection of winds due to Earth's rotation, emphasizing the conservation of angular momentum in directing flows rather than the conservation of linear momentum as Hadley suggested;[87] Hadley's assumption led to an underestimation of the deflection by a factor of two.

[79] The acceptance of the Coriolis force in shaping global winds led to debate among German atmospheric scientists beginning in the 1870s over the completeness and validity of Hadley's explanation, which narrowly explained the behavior of initially meridional motions.

[89] In 1899, William Morris Davis, a professor of physical geography at Harvard University, gave a speech at the Royal Meteorological Society criticizing Hadley's theory for its failure to account for the transition of an initially unbalanced flow to geostrophic balance.

[90] Davis and other meteorologists in the 20th century recognized that the movement of air parcels along Hadley's envisaged circulation was sustained by a constant interplay between the pressure gradient and Coriolis forces rather than the conservation of angular momentum alone.

[91] Ultimately, while the atmospheric science community considered the general ideas of Hadley's principle valid, his explanation was viewed as a simplification of more complex physical processes.

[99] Paleoclimate reconstructions of trade winds and rainfall patterns suggest that the Hadley circulation changed in response to natural climate variability.

Variation in insolation during the mid- to late-Holocene resulted in a southward migration of the Northern Hemisphere Hadley cell's ascending and descending branches closer to their present-day positions.

In contrast, the AR6 assessed that it was likely that the Southern Hemisphere Hadley cell's poleward expansion was due to anthropogenic influence;[104] this finding was based on CMIP5 and CMIP6 climate models.

[110] The magnitude of long-term changes in the circulation strength are thus uncertain due to the influence of large interannual variability and the poor representation of the distribution of latent heat release in reanalyses.

[111] Results from climate models suggest that the impact of internal variability (such as from the Pacific decadal oscillation) and the anthropogenic influence on the expansion of the Hadley circulation since the 1980s have been comparable.

[112] The physical processes by which the Hadley circulation expands by human influence are unclear but may be linked to the increased warming of the subtropics relative to other latitudes in both the Northern and Southern hemispheres.

These changes have influenced regional precipitation amounts and variability, including drying trends over southern Australia, northeastern China, and northern South Asia.

[21] A terrestrial atmosphere subject to excess equatorial heating tends to maintain an axisymmetric Hadley circulation with rising motions near the equator and sinking at higher latitudes.

[28] Venus, which rotates slowly, may have Hadley cells that extend farther poleward than Earth's, spanning from the equator to high latitudes in each of the northern and southern hemispheres.

[21][131] Its broad Hadley circulation would efficiently maintain the nearly isothermal temperature distribution between the planet's pole and equator and vertical velocities of around 0.5 cm/s (0.018 km/h; 0.011 mph).

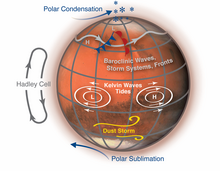

During most of the Martian year, when a single Hadley cell prevails, its rising and sinking branches are located at 30° and 60° latitude, respectively, in global climate modelling.

[135][138] While latent heating from phase changes associated with water drive much of the ascending motion in Earth's Hadley circulation, ascent in Mars' Hadley circulation may be driven by radiative heating of lofted dust and intensified by the condensation of carbon dioxide near the polar ice cap of Mars' wintertime hemisphere, steepening pressure gradients.

[142] The distribution of convective methane clouds on Titan and observations from Huygens spacecraft suggest that the rising branch of its Hadley circulation occurs in the mid-latitudes of its summer hemisphere.