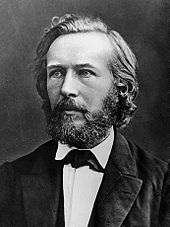

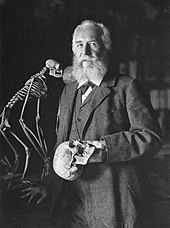

Ernst Haeckel

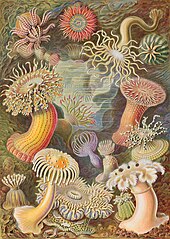

He discovered, described and named thousands of new species, mapped a genealogical tree relating all life forms and coined many terms in biology, including ecology,[2] phylum,[3] phylogeny,[4] and Protista.

[12][better source needed] He then studied medicine in Berlin and Würzburg, particularly with Albert von Kölliker, Franz Leydig, Rudolf Virchow (with whom he later worked briefly as assistant), and with the anatomist-physiologist Johannes Peter Müller (1801–1858).

[23] This organization lasted until 1933 and included such notable members as Wilhelm Ostwald, Georg von Arco (1869–1940), Helene Stöcker and Walter Arthur Berendsohn.

Although Haeckel's ideas are important to the history of evolutionary theory, and although he was a competent invertebrate anatomist most famous for his work on radiolaria, many speculative concepts that he championed are now considered incorrect.

For example, at the time when Darwin published On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (1859), Haeckel postulated that evidence of human evolution would be found in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia).

He described these theoretical remains in great detail and even named the as-yet unfound species, Pithecanthropus alalus, and instructed his students such as Richard and Oskar Hertwig to go and find it.

Some scientists of the day suggested[33] Dubois' Java Man as a potential intermediate form between modern humans and the common ancestor we share with the other great apes.

Haeckel put forward a racist[35] doctrine of evolutionary polygenism based on the ideas of the linguist August Schleicher, in which several different language groups had arisen separately from speechless prehuman Urmenschen (German: proto-humans), which themselves had evolved from simian ancestors.

He became a key figure in social darwinism and leading proponent of scientific racism, stating for instance:[39] The Caucasian, or Mediterranean man (Homo Mediterraneus), has from time immemorial been placed at the head of all the races of men, as the most highly developed and perfect.

This species alone (with the exception of the Mongolian) has had an actual history; it alone has attained to that degree of civilisation which seems to raise men above the rest of nature.Haeckel divided human beings into ten races, of which the Caucasian was the highest and the primitives were doomed to extinction.

[40] In his view, 'Negroes' were savages and Whites were the most civilised: for instance, he claimed that '[t]he Negro' had stronger and more freely movable toes than any other race, which, he argued, was evidence of their being less evolved, and which led him to compare them to '"four-handed" Apes'.

[41] In his Ontogeny and Phylogeny Harvard paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould wrote: "[Haeckel's] evolutionary racism; his call to the German people for racial purity and unflinching devotion to a 'just' state; his belief that harsh, inexorable laws of evolution ruled human civilization and nature alike, conferring upon favored races the right to dominate others ... all contributed to the rise of Nazism.

[44] However, in 2009 Robert J. Richards noted: "Haeckel, on his travels to Ceylon and Indonesia, often formed closer and more intimate relations with natives, even members of the untouchable classes, than with the European colonials."

and says the Nazis rejected Haeckel, since he opposed antisemitism, while supporting ideas they disliked (for instance atheism, feminism, internationalism, pacifism etc.).

[45] The Jena Declaration, published by the German Zoological Society, rejects the idea of human "races" and distances itself from the racial theories of Ernst Haeckel and other 20th century scientists.

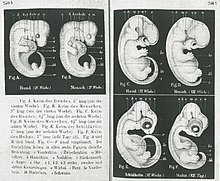

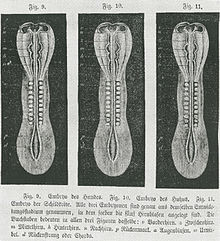

It was agreed by all European evolutionists that all vertebrates looked very similar at an early stage, in what was thought of as a common ideal type, but there was a continuing debate from the 1820s between the Romantic recapitulation theory that human embryos developed through stages of the forms of all the major groups of adult animals, literally manifesting a sequence of organisms on a linear chain of being, and Karl Ernst von Baer's opposing view, stated in von Baer's laws of embryology, that the early general forms diverged into four major groups of specialised forms without ever resembling the adult of another species, showing affinity to an archetype but no relation to other types or any transmutation of species.

By the time Haeckel was teaching he was able to use a textbook with woodcut illustrations written by his own teacher Albert von Kölliker, which purported to explain human development while also using other mammalian embryos to claim a coherent sequence.

[54]: 264–267 [55] Darwin's On the Origin of Species, which made a powerful impression on Haeckel when he read it in 1864, was very cautious about the possibility of ever reconstructing the history of life, but did include a section reinterpreting von Baer's embryology and revolutionising the field of study, concluding that "Embryology rises greatly in interest, when we thus look at the embryo as a picture, more or less obscured, of the common parent-form of each great class of animals."

[56] Haeckel disregarded such caution, and in a year wrote his massive and ambitious Generelle Morphologie, published in 1866, presenting a revolutionary new synthesis of Darwin's ideas with the German tradition of Naturphilosophie going back to Goethe and with the progressive evolutionism of Lamarck in what he called Darwinismus.

The images were reworked to match in size and orientation, and though displaying Haeckel's own views of essential features, they support von Baer's concept that vertebrate embryos begin similarly and then diverge.

The first published concerns came from Ludwig Rütimeyer, a professor of zoology and comparative anatomy at the University of Basel who had placed fossil mammals in an evolutionary lineage early in the 1860s and had been sent a complimentary copy.

At the end of 1868 his review in the Archiv für Anthropologie wondered about the claim that the work was "popular and scholarly", doubting whether the second was true, and expressed horror about such public discussion of man's place in nature with illustrations such as the evolutionary trees being shown to non-experts.

Though he made no suggestion that embryo illustrations should be directly based on specimens, to him the subject demanded the utmost "scrupulosity and conscientiousness" and an artist must "not arbitrarily model or generalise his originals for speculative purposes" which he considered proved by comparison with works by other authors.

In 1891 Haeckel made the excuse that this "extremely rash foolishness" had occurred in undue haste but was "bona fide", and since repetition of incidental details was obvious on close inspection, it is unlikely to have been intentional deception.

In the introduction to his 1871 The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, Darwin gave particular praise to Haeckel, writing that if Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte "had appeared before my essay had been written, I should probably never have completed it".

[54]: 285–288 [57] Later in 1874, Haeckel's simplified embryology textbook Anthropogenie made the subject into a battleground over Darwinism aligned with Bismarck's Kulturkampf ("culture struggle") against the Catholic Church.

Though Haeckel's views had attracted continuing controversy, there had been little dispute about the embryos and he had many expert supporters, but Wilhelm His revived the earlier criticisms and introduced new attacks on the 1874 illustrations.

It was a bestselling, provocatively illustrated book in German, titled Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte, published in Berlin in 1868, and translated into English as The History of Creation in 1876.

[91] Haeckel also believed that Germany should be governed by an authoritarian political system, and that inequalities both within and between societies were an inevitable product of evolutionary law.

[99] This opinion was also shared by the scholarly journal, Der Biologe, which celebrated Haeckel's 100th birthday, in 1934, with several essays acclaiming him as a pioneering thinker of Nazism.