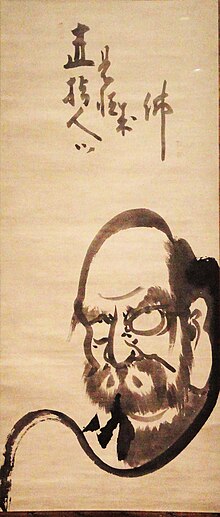

Hakuin Ekaku

[web 1] While never having received formal dharma transmission, he is regarded as the reviver of the Japanese Rinzai school from a period of stagnation, focusing on rigorous training methods integrating meditation and koan practice.

At the age of fifteen, he obtained consent from his parents to join the monastic life, and was ordained at the local Zen temple, Shōin-ji, by the residing priest Tanrei Soden.

[2] Travelling with twelve other monks, Hakuin made his way to Zuiun-ji, the residence of Baō Rōjin, a respected scholar but also a tough-minded teacher.

[12] His mental dispositions were unchanged, and attachment and aversion still prevailed in daily life, a tendency which he could not correct through "ordinary intellectual means.

"[13][note 1] His mental anguish even worsened when, at twenty-six, he read that "all wise men and eminent priests who lack the Bodhi-mind fall into Hell".

[17] Hakuin's early extreme exertions affected his health, and at one point in his young life he fell ill for almost two years, experiencing what would now probably be classified as a nervous breakdown by Western medicine.

Well into his seventies, he claimed to have more physical strength than he had at age thirty, being able to sit in zazen meditation or chant sutras for an entire day without fatigue.

He was soon installed as head priest, a capacity in which he would serve for the next half-century, giving Torin Sosho, who had followed-up Tanrei, as his "master" when enscribing himself in the Mioshi-ji bureaucracy.

[21]It was around this time that he adopted the name "Hakuin", which means "concealed in white", referring to the state of being hidden in the clouds and snow of mount Fuji.

A well-known anecdote took place in this period: A beautiful Japanese girl whose parents owned a food store lived near Hakuin.

"[26]Shortly before his death, Hakuin wrote An elderly monk of eighty-four, I welcome in yet one more yearAnd I owe it all – everything – to the Sound of One Hand barrier.

Like his predecessors Shidō Bu'nan (Munan) (1603–1676) and Dōkyō Etan (Shoju Rojin, "The Old Man of Shōju Hermitage") (1642–1721), Hakuin stressed the importance of kensho and post-satori practice, deepening one's understanding and working for the benefit of others.

Hakuin emphasized the need for "post-satori training",[30][31] purifying the mind of karmic tendencies and [W]hipping forward the wheel of the Four Universal Vows, pledging yourself to benefit and save all sentient beings while striving every minute of your life to practice the great Dharma giving.

Yet, they also had to sustain the "great doubt", going beyond their initial awakening and further deepen their insight struggling with "difficult-to-pass" (nanto) koans, which Hakuin seems to have inherited from his teachers.

This further training and awakening culminates in a full integration of understanding and quietude with the action of daily life, and bodhicitta, upholding the four bodhisattva-vows and striving to liberate all living beings.

[note 4]Kannon Bosatsu is Kanzeon (Avalokiteshvara, Guanyin), the bodhisattva of great compassion, who hears the sounds of all people suffering in this world.

He believed his "Sound of One Hand" to be more effective in generating the great doubt, and remarked that "its superiority to the former methods is like the difference between cloud and mud".

When first meeting Shōju Rōjin, Hakuin boasted of the "depth" and "clarity" of his own Zen understanding in the form of an elegant verse put down on a sheet of paper.

"[52]Regarding his final awakening, in his biography Wild Ivy Hakuin wrote “Of all the sages and holy monks since the time of the Buddha Krakucchanda, those lacking bodhicitta have all fallen into the realm of the demons.” For long I wondered what these words meant....

Shǒshun conjects that these remedies were worked out by Hakuin on his own, from "a combination of traditional medical and meditation texts and folk therapies current at the time.

[60] In the preface to Yasenkanna, attributed by Hakuin to a disciple called "Hunger and Cold, the Master of Poverty Hermitage," Hakuin explains that a long life can be attained by disciplining the body through gathering the ki, the life-force or "the fire or heat in your mind (heart)," in the tanden or lower belly, producing "the true elixir" (shintan), which is "not something located apart from the self.

This tanden of mine in the ocean of ki – the lower back and legs, the arches of the feet – is all the home and native place of my original being.

This tanden of mine in the ocean of ki – the lower back and legs, the arches of the feet – is all the Pure Land of my own mind.

[73] Hakuin put a strong emphasis on kensho and post-satori practice, following the examples of his dharma-predecessors Gudō Toshoku (1577–1661), Shidō Bu'nan (Munan)(1603–1676), and his own teacher Shoju Rojin (Dokyu Etan), 1642–1721).

[77] Heine and Wright note that:[78] ... regardless of its inclusion of Pure Land elements, the fact remained that the Ōbaku school, with its group practice of zazen on the platforms in a meditation hall and its emphasis on keeping the precepts, represented a type of communal monastic discipline far more rigorous than anything that existed at the time in Japanese Buddhism.As a result of their approach, which caused a stir in Japan, many Rinzai and Sōtō masters undertook reforming and revitalizing their own monastic institutions, partly incorporating Ōbaku, partly rejecting them.

Kogetsu Zenzai welcomed their influence, and Rinzai master Ungo Kiyō even began implementing the use of nembutsu into his training regimen at Zuigan-ji.

While the communal training of the Ōbaku-school was emulated, The followers of Hakuin Ekaku (1687—1769) tried to purge the elements of Ōbaku Zen they found objectionable.

They suppressed the Pure Land practice of reciting Amida Buddha's name, deemphasized the Vinaya, and replaced sutra study with a more narrow focus on traditional koan collections.

Thanks to his upbringing as a commoner and his many travels around the country, he was able to relate to the rural population, and served as a sort of spiritual father to the people in the areas surrounding Shoin-ji.

His paintings were meant to capture Zen values, serving as sorts of "visual sermons" that were extremely popular among the laypeople of the time, many of whom were illiterate.