Huayan

These Huayan "patriarchs" (though they did not call themselves as such) were erudite scholar-practitioner who created a unique tradition of exegesis, study and practice through their writings and oral teachings.

The school, which had been dependent upon the support it received from the government, suffered severely during the Great Buddhist Persecution of the Huichang era (841–845), initiated by Emperor Wuzong of Tang.

[31] Various masters from these non-Chinese kingdoms are known, such as Xianyan (1048-1118) from Kailong temple in Khitan Upper capital, Hengce (1049-1098), Tongli dashi from Yanjing, Daoshen (1056?-1114?

However, he also recommended that those of "middling and lesser faculties...can choose to practice a single method according to their preference, be it the exoteric or esoteric.”[36] Daochen's esoteric teachings focused on the dharani of Cundi which he saw as "the mother of all Buddhas and the life of all bodhisattvas" and also drew on the Mani mantra.

[37] Another Liao Tangut work which survives from this period is The Meaning of the Luminous One-Mind of the Ultimate One Vehicle (Jiujing yicheng yuan-ming xinyao 究竟一乘圓明心要) by Tongli Hengce (通理恆策, 1048–1098).

[38] The chief Chinese Huayan figures of the Song dynasty revival were Changshui Zixuan (子璇, 965–1038), Jinshui Jingyuan (靜源, 1011–1088), and Yihe (義和, c. early twelfth century).

One important event during the early Ming was when the eminent Huayan monk Huijin (1355-1436) was invited by the Xuande Emperor (1399-1435) to the imperial palace to preside over the copying of ornate manuscripts of the Buddhāvataṃsaka, Prajñāpāramitā, Mahāratnakūṭa, and Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtras.

[43] During the Qing dynasty (1644-1912), Huayan philosophy continued to develop and exert a strong influence on Chinese Buddhism and its other traditions, including Chan and Pure Land.

[47] For the scholar monk Xufa, the practice of nianfo (contemplation of the Buddha) was a universal method suitable for everyone which was taught in the Avatamsaka Sutra and could lead to an insight into the Huayan teachings of interpenetration.

[49] After Uisang returned to Korea in 671, established the school and wrote various Hwaôm works, including a popular poem called the Beopseongge, also known as the Diagram of the Realm of Reality, which encapsulated the Huayan teaching.

[50][51] In this effort, he was greatly aided by the powerful influences of his friend Wonhyo, who also studied and drew on Huayan thought and is considered a key figure of Korean Hwaôm.

[55] Royal support allowed various Hwaôm monasteries to be constructed on all five of Korea's sacred mountains, and the tradition became the main force behind the unification of various Korean Buddhist cults, such as those of Manjushri, Maitreya and Amitabha.

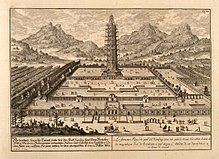

[62] Huayan studies were founded in Japan in 736 when the scholar-priest Rōben (689–773), originally a monk of the East Asian Yogācāra tradition, invited the Korean monk Shinjō (traditional Chinese: 審祥; ; pinyin: Shenxiang; Korean pronunciation: Simsang) to give lectures on the Avatamsaka Sutra at Kinshōsen Temple (金鐘山寺, also 金鐘寺 Konshu-ji or Kinshō-ji), the origin of later Tōdai-ji.

[74] Likewise, Huayan thought was important to some Chinese Pure Land thinkers, such as the Ming exegete Yunqi Zuhong (1535–1615) and the modern lay scholar Yang Wenhui (1837–1911).

[79] According to Thomas Cleary, similar Huayan influences can be found in the works of other Tang dynasty Chan masters like Yunmen Wenyan (d. 949) and Fayen Wenyi (885-958).

According to Paul Williams, the Avataṃsaka Sūtra is not a systematic philosophical work, though it does contain various Mahayana teachings reminiscent of Madhyamaka and Yogacara, as well as mentioning a pure untainted awareness or consciousness (amalacitta).

Thus does infinity enter into one, yet each unit's distinct, with no overlap....In each atom are innumerable lights pervading the lands of the ten directions, all showing the Buddhas’ enlightenment practices.

"[93] The Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana (Dasheng Qixin Lun, 大乘起信論) was another key scriptural source for Huayan masters like Fazang and Zongmi, both of whom wrote commentaries on this treatise.

Instead it was concerned with specific doctrines, ideas and metaphors (such as nature origination, the dependent arising of the dharmadhatu, interfusion, and the six characteristics of all dharmas) which was inspired by scripture.

[110][107] This doctrine is described by Wei Daoru as the idea that "countless dharmas (all phenomena in the world) are representations of the wisdom of Buddha without exception" and that "they exist in a state of mutual dependence, interfusion and balance without any contradiction or conflict.

The term derives from chapter 32 of the Avatamsaka Sutra, titled Nature Origination of the Jewel King Tathagata (Baowang rulai xingqi pin, Skt.

[144] Regarding the Huayan position, Fung says, "the central element in Fa-tsang’s philosophy is a permanently immutable 'mind' which is universal or absolute in its scope, and is the basis for all phenomenal manifestations.

[3][41][150] These various elements might also be combined in ritual manuals such as The Practice of Samantabhadra's Huayan Dharma Realm Aspiration and Realization (華嚴普賢行願修證儀, Taisho Supplement, No.

[3] Regular chanting of important passages from the sutra is also common, particularly the Bhadracaryāpraṇidhāna (The Aspiration Prayer for Good Conduct), sometimes called the "Vows of Samantabhadra".

[159] The practice of Buddha contemplation was promoted by various figures, such as the Huayan patriarchs Chengguan, Zongmi, the Goryeo monk Gyunyeo (923–973) and Peng Shaosheng, a householder scholar of the Qing dynasty.

[169] Jueyuan, a Huayan monk from Yuanfu Temple during the Liao Dynasty and author of the Dari jing yishi yanmi chao, practiced esoteric rituals like Homa and Abhiseka based on the Vairocanābhisaṃbodhi Sūtra and the tradition of Yixing.

[172] Important esoteric texts used in the Liao tradition included the: Cundī-dhāraṇī, the Usṇīsavijayā-dhāranī, the Nīlakaṇthaka-dhāranī and the Sutra on the Great Dharma Torch Dhāraṇī ( 大法炬陀羅尼 經, Da faju tuoluoni jing) among others.

[181] This interpenetration of all elements of the path to awakening is also a consequence of the Huayan view of time, which sees all moments as interfused (including a sentient being's present practice and their eventual future Buddhahood aeons from now).

[182] This doctrine of "enlightenment at the stage of faith" (信滿成佛, xinman cheng fo) was a unique feature of Huayan and was first introduced by Fazang though it has a precedent in a passage of the Avatamsaka Sutra.

Thus, according to Li Tongxuan "there is no other enlightenment" than simply following the bodhisattva path, and furthermore:Primordial wisdom is made manifest through meditation; cultivation does not create it or bring it into being.