Burr–Hamilton duel

The Burr–Hamilton duel took place in Weehawken, New Jersey, between Aaron Burr, the third U.S. vice president at the time, and Alexander Hamilton, the first and former Secretary of the Treasury, at dawn on July 11, 1804.

The duel was the culmination of a bitter rivalry that had developed over years between both men, who were high-profile politicians in the newly-established United States, founded following the victorious American Revolution and its associated Revolutionary War.

Hamilton was transported across the Hudson River for treatment in present-day Greenwich Village in New York City, where he died the following day, on July 12, 1804.

The conflict began in 1791 when Burr won a United States Senate seat from Philip Schuyler, Hamilton's father-in-law, who would have supported Federalist policies.

The Electoral College then deadlocked in the 1800 presidential election, during which Hamilton's maneuvering in the U.S. House of Representatives played a factor in Thomas Jefferson's winning the presidency over Burr.

In a January 4, 1801, letter to McHenry, Hamilton wrote: Nothing has given me so much chagrin as the Intelligence that the Federal party were thinking seriously of supporting Mr. Burr for president.

The Constitution stipulated that if two candidates with an Electoral College majority were tied, the election would be moved to the House of Representatives—which was controlled by the Federalists, at this point, many of whom were loath to vote for Jefferson.

On April 24, 1804, the Albany Register published a letter opposing Burr's gubernatorial candidacy[10] which was originally sent from Charles D. Cooper to Hamilton's father-in-law, former senator Philip Schuyler.

[11] It made reference to a previous statement by Cooper: "General Hamilton and Judge Kent have declared in substance that they looked upon Mr. Burr to be a dangerous man, and one who ought not be trusted with the reins of government."

Cooper went on to emphasize that he could describe in detail "a still more despicable opinion which General Hamilton has expressed of Mr. Burr" at a political dinner.

[12] Burr responded in a letter delivered by William P. Van Ness which pointed particularly to the phrase "more despicable" and demanded "a prompt and unqualified acknowledgment or denial of the use of any expression which would warrant the assertion of Dr.

[13] A recurring theme in their correspondence is that Burr seeks avowal or disavowal of anything that could justify Cooper's characterization, while Hamilton protests that there are no specifics.

Burr replied on June 21, 1804, also delivered by Van Ness, stating that "political opposition can never absolve gentlemen from the necessity of a rigid adherence to the laws of honor and the rules of decorum".

General Hamilton cannot recollect distinctly the particulars of that conversation, so as to undertake to repeat them, without running the risk of varying or omitting what might be deemed important circumstances.

The expressions are entirely forgotten, and the specific ideas imperfectly remembered; but to the best of his recollection it consisted of comments on the political principles and views of Colonel Burr, and the results that might be expected from them in the event of his election as Governor, without reference to any particular instance of past conduct or private character.

[18] Thomas Fleming offers the theory that Burr may have been attempting to recover his honor by challenging Hamilton, whom he considered to be the only gentleman among his detractors, in response to the slanderous attacks against his character published during the 1804 gubernatorial campaign.

Joanne Freeman speculates that Hamilton intended to accept the duel and throw away his shot in order to satisfy his moral and political codes.

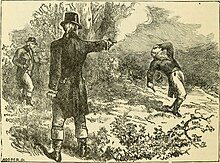

[20] In the early morning of July 11, 1804, Burr and Hamilton departed from Manhattan by separate boats and rowed across the Hudson River to a spot known as the Heights of Weehawken, New Jersey, a popular dueling ground below the towering cliffs of the Palisades.

According to the principles of the code duello, Burr was perfectly justified in taking deadly aim at Hamilton and firing to kill.Hosack wrote his account on August 17, about one month after the duel had taken place.

[28] He gives a very clear picture of the events in a letter to William Coleman: When called to him upon his receiving the fatal wound, I found him half sitting on the ground, supported in the arms of Mr. Pendleton.

I now rubbed his face, lips, and temples with spirits of hartshorn, applied it to his neck and breast, and to the wrists and palms of his hands, and endeavoured to pour some into his mouth.

He asked me once or twice how I found his pulse; and he informed me that his lower extremities had lost all feeling, manifesting to me that he entertained no hopes that he should long survive.

As they were taking their places, he asked that the proceedings stop, adjusted his spectacles, and slowly, repeatedly, sighted along his pistol to test his aim.

In the attachment to that letter, Hamilton argued against Burr's character on numerous scores: he suspected Burr "on strong grounds of having corruptly served the views of the Holland Company;" "his very friends do not insist on his integrity"; "he will court and employ able and daring scoundrels;" he seeks "Supreme power in his own person" and "will in all likelihood attempt a usurpation," and so forth.

[50] After being attended by Hosack, the mortally wounded Hamilton was taken to the home of William Bayard Jr. in the present-day Greenwich Village section of New York City, where he was given communion by Bishop Benjamin Moore.

[52][53] He died the next day after seeing his wife Elizabeth and their children, in the presence of more than 20 friends and family members; he was buried in the Trinity Churchyard Cemetery in Manhattan.

[54] Following the duel, Burr fled to St. Simons Island, Georgia, where he stayed at the plantation of Pierce Butler, but he soon returned to Washington, D.C. to complete his term as vice president.

[57] He presided over the impeachment trial of Samuel Chase "with the dignity and impartiality of an angel, but with the rigor of a devil", according to a Washington newspaper.

[59] A 14-foot marble cenotaph was constructed where Hamilton was believed to have fallen, consisting of an obelisk topped by a flaming urn and a plaque with a quotation from Horace, the whole structure surrounded by an iron fence.

[61] From 1820 to 1857, the site was marked by two stones with the names Hamilton and Burr placed where they were thought to have stood during the duel, but a road was built through the site in 1858 from Hoboken, New Jersey, to Fort Lee, New Jersey; all that remained of those memorials was an inscription on a boulder where Hamilton was thought to have rested after the duel, but there are no primary accounts which confirm the boulder anecdote.