Hamlet

After seeing the Player King murdered by his rival pouring poison in his ear, Claudius abruptly rises and runs from the room; for Hamlet, this is proof of his uncle's guilt.

Back at Elsinore, Hamlet explains to Horatio that he had discovered Claudius's letter among Rosencrantz and Guildenstern's belongings and replaced it with a forged copy indicating that his former friends should be killed instead.

Horatio promises to recount the full story of what happened, and Fortinbras, seeing the entire Danish royal family dead, takes the crown for himself and orders a military funeral to honour Hamlet.

Its hero, Lucius ("shining, light"), changes his name and persona to Brutus ("dull, stupid"), playing the role of a fool to avoid the fate of his father and brothers, and eventually slaying his family's killer, King Tarquinius.

Modern editors generally follow this traditional division but consider it unsatisfactory; for example, after Hamlet drags Polonius's body out of Gertrude's bedchamber, there is an act-break[58] after which the action appears to continue uninterrupted.

[77][78][79][80][81][82][83] In 1768, Voltaire wrote a negative review of Hamlet, stating that "it is vulgar and barbarous drama, which would not be tolerated by the vilest populace of France or Italy... one would imagine this piece to be a work of a drunken savage".

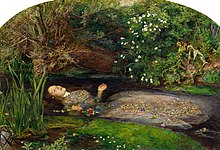

There is no subplot, but the play presents the affairs of the courtier Polonius, his daughter, Ophelia, and his son, Laertes—who variously deal with madness, love and the death of a father in ways that contrast with Hamlet's.

[86] Hamlet's enquiring mind has been open to all kinds of ideas, but in act five he has decided on a plan, and in a dialogue with Horatio he seems to answer his two earlier soliloquies on suicide: "We defy augury.

[98] Pauline Kiernan argues that Shakespeare changed English drama forever in Hamlet because he "showed how a character's language can often be saying several things at once, and contradictory meanings at that, to reflect fragmented thoughts and disturbed feelings".

Dialogue refers explicitly to the German city of Wittenberg where Hamlet, Horatio, and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern attend university, implying where the Protestant reformer Martin Luther nailed the Ninety-five Theses to the church door in 1517.

[114][115][113] Sigmund Freud’s thoughts regarding Hamlet were first published in his book The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), as a footnote to a discussion of Sophocles’ tragedy, Oedipus Rex, all of which is part of his consideration of the causes of neurosis.

But the difference in the "psychic life" of the two civilizations that produced each play, and the progress made over time of "repression in the emotional life of humanity" can be seen in the way the same material is handled by the two playwrights: In Oedipus Rex incest and murder are brought into the light as might occur in a dream, but in Hamlet these impulses "remain repressed" and we learn of their existence through Hamlet's inhibitions to act out the revenge, while he is shown to be capable of acting decisively and boldly in other contexts.

"[124] John Barrymore's long-running 1922 performance in New York, directed by Thomas Hopkins, "broke new ground in its Freudian approach to character", in keeping with the post-World War I rebellion against everything Victorian.

[135] In Lacan's analysis, Hamlet unconsciously assumes the role of phallus—the cause of his inaction—and is increasingly distanced from reality "by mourning, fantasy, narcissism and psychosis", which create holes (or lack) in the real, imaginary, and symbolic aspects of his psyche.

As scholar Christopher N. Warren argues, Paradise Lost's Satan "undergoes a transformation in the poem from a Hamlet-like avenger into a Claudius-like usurper," a plot device that supports Milton's larger Republican internationalist project.

In Angela Carter's Wise Children, To be or not to be is reworked as a song and dance routine, and Iris Murdoch's The Black Prince has Oedipal themes and murder intertwined with a love affair between a Hamlet-obsessed writer, Bradley Pearson, and the daughter of his rival.

It is sometimes argued that the crew of the ship Red Dragon, anchored off Sierra Leone, performed Hamlet in September 1607;[162][163][164] however, this claim is based on a 19th-century insert of a 'lost' passage into a period document, and is today widely regarded as a hoax, likely to have been perpetrated by John Payne Collier.

[166] Oxford editor George Hibbard argues that, since the contemporary literature contains many allusions and references to Hamlet (only Falstaff is mentioned more, from Shakespeare), the play was surely performed with a frequency that the historical record misses.

[173] David Garrick at Drury Lane produced a version that adapted Shakespeare heavily; he declared: "I had sworn I would not leave the stage till I had rescued that noble play from all the rubbish of the fifth act.

[183] In the United Kingdom, the actor-managers of the Victorian era (including Kean, Samuel Phelps, Macready, and Henry Irving) staged Shakespeare in a grand manner, with elaborate scenery and costumes.

George Bernard Shaw's praise for Johnston Forbes-Robertson's performance contains a sideswipe at Irving: "The story of the play was perfectly intelligible, and quite took the attention of the audience off the principal actor at moments.

[186] In stark contrast to earlier opulence, William Poel's 1881 production of the Q1 text was an early attempt at reconstructing the Elizabethan theatre's austerity; his only backdrop was a set of red curtains.

[h] In France, Charles Kemble initiated an enthusiasm for Shakespeare; and leading members of the Romantic movement such as Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas saw his 1827 Paris performance of Hamlet, particularly admiring the madness of Harriet Smithson's Ophelia.

[199][k] The most famous aspect of the production is Craig's use of large, abstract screens that altered the size and shape of the acting area for each scene, representing the character's state of mind spatially or visualising a dramaturgical progression.

[207] Similarly, Czech directors have used the play at times of occupation: a 1941 Vinohrady Theatre production "emphasised, with due caution, the helpless situation of an intellectual attempting to endure in a ruthless environment".

[214] Although "posterity has treated Maurice Evans less kindly", throughout the 1930s and 1940s he was regarded by many as the leading interpreter of Shakespeare in the United States and in the 1938/39 season he presented Broadway's first uncut Hamlet, running four and a half hours.

[220] Other New York portrayals of Hamlet of note include that of Ralph Fiennes's in 1995 (for which he won the Tony Award for Best Actor)—which ran, from first preview to closing night, a total of one hundred performances.

Instead it's an intelligent, beautifully read ..."[221] Stacy Keach played the role with an all-star cast at Joseph Papp's Delacorte Theater in the early 1970s, with Colleen Dewhurst's Gertrude, James Earl Jones's King, Barnard Hughes's Polonius, Sam Waterston's Laertes and Raul Julia's Osric.

William Hurt (at Circle Repertory Company off-Broadway, memorably performing "To be, or not to be" while lying on the floor), Jon Voight at Rutgers,[clarification needed] and Christopher Walken (fiercely) at Stratford, Connecticut, have all played the role, as has Diane Venora at The Public Theatre.

[258] Branagh set the film with late 19th-century costuming and furnishings, a production in many ways reminiscent of a Russian novel of the time,[259] and Blenheim Palace, built in the early 18th century, became Elsinore Castle in the external scenes.