Harlem

With job losses during the Great Depression of the 1930s and the deindustrialization of New York City after World War II, rates of crime and poverty increased significantly.

[13][14][15] Residents and other critics seeking to prevent this renaming of the area have labelled the SoHa brand as "insulting and another sign of gentrification run amok"[16] and have said that "the rebranding not only places their neighborhood's rich history under erasure but also appears to be intent on attracting new tenants, including students from nearby Columbia University".

"[17] By 2017, New York State Senator Brian Benjamin also worked to render the practice of rebranding historically recognized neighborhoods illegal.

[35] The early-20th century Great Migration of black people to northern industrial cities was fueled by their desire to leave behind the Jim Crow South, seek better jobs and education for their children, and escape a culture of lynching violence; during World War I, expanding industries recruited black laborers to fill new jobs, thinly staffed after the draft began to take young men.

These groups wanted the city to force landlords to improve the quality of housing by bringing them up to code, to take action against rats and roaches, to provide heat during the winter, and to keep prices in line with existing rent control regulations.

[41] Typically, existing structures were torn down and replaced with city-designed and managed properties that would, in theory, present a safer and more pleasant environment than those available from private landlords.

Though the federal government's Model Cities Program spent $100 million on job training, health care, education, public safety, sanitation, housing, and other projects over a ten-year period, Harlem showed no improvement.

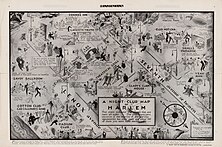

In the 1920s and 1930s, between Lenox and Seventh Avenues in central Harlem, over 125 entertainment venues were in operation, including speakeasies, cellars, lounges, cafes, taverns, supper clubs, rib joints, theaters, dance halls, and bars and grills.

In 2013, residents staged a sidewalk sit-in to protest a five-days-a-week farmers market that would shut down Macombs Place at 150th Street.

The Main Ingredient, Frankie Lymon & The Teenagers, Black Ivory, Cameo, Keith Sweat, Freddie Jackson, Alyson Williams, Johnny Kemp, Teddy Riley, Dave Wooley, and others got their start in Harlem.

Manhattan's contributions to hip-hop stems largely from artists with Harlem roots such as Doug E. Fresh, Big L, Kurtis Blow, The Diplomats, Mase or Immortal Technique.

[73] In the 1920s, African-American pianists who lived in Harlem invented their own style of jazz piano, called stride, which was heavily influenced by ragtime.

Especially in the years before World War II, Harlem produced popular Christian charismatic "cult" leaders, including George Wilson Becton and Father Divine.

This policy rated neighborhoods, such as Central Harlem, as unappealing based on the race, ethnicity, and national origins of the residents.

[3] Comparably, wealthy and white residents in New York City neighborhoods were approved more often for housing loans and investment applications.

However, rather than compete with the established mobs, gangs concentrated on the "policy racket", also called the numbers game, or bolita in East Harlem.

According to Francis Ianni, "By 1925 there were thirty black policy banks in Harlem, several of them large enough to collect bets in an area of twenty city blocks and across three or four avenues.

"[145] By the early 1950s, the total money at play amounted to billions of dollars, and the police force had been thoroughly corrupted by bribes from numbers bosses.

One of the powerful early numbers bosses was a woman, Madame Stephanie St. Clair, who fought gun battles with mobster Dutch Schultz over control of the lucrative trade.

[147] The popularity of playing the numbers waned with the introduction of the state lottery, which is legal but has lower payouts and has taxes collected on winnings.

In the 1980s, use of crack cocaine became widespread, which produced collateral crime as addicts stole to finance their purchasing of additional drugs, and as dealers fought for the right to sell in particular regions, or over deals gone bad.

[151] With the end of the "crack wars" in the mid-1990s, and with the initiation of aggressive policing under mayors David Dinkins and his successor Rudy Giuliani, crime in Harlem plummeted.

[3]: 14 The concentration of fine particulate matter, the deadliest type of air pollutant, in Central Harlem is 0.0079 milligrams per cubic metre (7.9×10−9 oz/cu ft), slightly more than the city average.

[3]: 13 In Central Harlem, 34% of residents are obese, 12% are diabetic, and 35% have high blood pressure, the highest rates in the city—compared to the citywide averages of 24%, 11%, and 28% respectively.

[164][165] Public health and scientific research studies have found evidence that experiencing racism creates and exacerbates chronic stress that can contribute to major causes of death, particularly for African-American and Hispanic populations in the United States, like cardiovascular diseases.

[125] Historical income segregation via redlining also positions residents to be more exposed to risks that contribute to adverse mental health status, inadequate access to healthy foods, asthma triggers, and lead exposure.

[174] In 2014, Central Harlem tracked worse in regards to home maintenance conditions, compared to the average rates Manhattan and New York City.

Meanwhile, 25% of Central Harlem households and 27% of adults reported seeing cockroaches (a potential trigger for asthma), a rate higher than the city average.

Neighborhood conditions are also indicators of population: in 2014, Central Harlem had 32 per 100,000 people hospitalized due to pedestrian injuries, higher than Manhattan's and the city's average.

In 2016, 270 adults per 10,000 residents visited the emergency department due to asthma, close to three times the average rates of both Manhattan and New York City.