Harmony

The principles of connection that govern these structures have been the subject of centuries worth of theoretical work and vernacular practice alike.

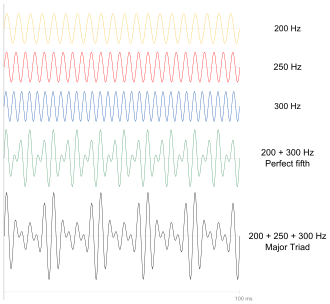

[4] Drawing both from music theoretical traditions and the field of psychoacoustics, its perception in large part consists of recognizing and processing consonance, a concept whose precise definition has varied throughout history, but is often associated with simple mathematical ratios between coincident pitch frequencies.

In the physiological approach, consonance is viewed as a continuous variable measuring the human brain's ability to 'decode' aural sensory input.

The notion of counterpoint seeks to understand and describe the relationships between melodic lines, often in the context of a polyphonic texture of several simultaneous but independent voices.

[1] The term harmony derives from the Greek ἁρμονία harmonia, meaning "joint, agreement, concord",[7][8] from the verb ἁρμόζω harmozō, "(Ι) fit together, join".

[11] Current dictionary definitions, while attempting to give concise descriptions, often highlight the ambiguity of the term in modern use.

[19] Emphasis on the precomposed in European art music and the written theory surrounding it shows considerable cultural bias.

The conception of musics that live in oral traditions as something composed with the use of improvisatory techniques separates them from the higher-standing works that use notation.

[20]Yet the evolution of harmonic practice and language itself, in Western art music, is and was facilitated by this process of prior composition, which permitted the study and analysis by theorists and composers of individual pre-constructed works in which pitches (and to some extent rhythms) remained unchanged regardless of the nature of the performance.

The English style was considered to have a sweeter sound, and was better suited to polyphony in that it offered greater linear flexibility in part-writing.

Coordinate harmony is the older Medieval and Renaissance tonalité ancienne, "The term is meant to signify that sonorities are linked one after the other without giving rise to the impression of a goal-directed development.

Interval cycles create symmetrical harmonies, which have been extensively used by the composers Alban Berg, George Perle, Arnold Schoenberg, Béla Bartók, and Edgard Varèse's Density 21.5.

[21] In pop music, unison singing is usually called doubling, a technique The Beatles used in many of their earlier recordings.

As a type of harmony, singing in unison or playing the same notes, often using different musical instruments, at the same time is commonly called monophonic harmonization.

The following are common intervals: When tuning notes using an equal temperament, such as the 12-tone equal temperament that has become ubiquitous in Western music, each interval is created using steps of the same size, producing harmonic relations marginally 'out of tune' from pure frequency ratios as explored by the ancient Greeks.

As such, additional accidentals are free to convey more nuanced information in the context of a passage of music and the other notes that make it up.

Even if identical in isolation, different spellings of enharmonic notes provide meaningful context when reading and analyzing music.

[citation needed] The consonant intervals are considered the perfect unison, octave, fifth, fourth and major and minor third and sixth, and their compound forms.

An interval is referred to as "perfect" when the harmonic relationship is found in the natural overtone series (namely, the unison 1:1, octave 2:1, fifth 3:2, and fourth 4:3).

The other basic intervals (second, third, sixth, and seventh) are called "imperfect" because the harmonic relationships are not found mathematically exact in the overtone series.

Other intervals, the second and the seventh (and their compound forms) are considered Dissonant and require resolution (of the produced tension) and usually preparation (depending on the music style[25]).

[26] In the Western tradition, in music after the seventeenth century, harmony is manipulated using chords, which are combinations of pitch classes.

In popular and jazz harmony, chords are named by their root plus various terms and characters indicating their qualities.

In many types of music, notably baroque, romantic, modern and jazz, chords are often augmented with "tensions".

The clearing of this tension usually sounds pleasant to the listener, though this is not always the case in late-nineteenth century music, such as Tristan und Isolde by Richard Wagner.

Tonal fusion contributes to the perceived consonance of a chord,[28] describing the degree to which multiple pitches are heard as a single, unitary tone.

These differences may not be readily apparent in tempered contexts but can explain why major triads are generally more prevalent than minor triads and major-minor sevenths are generally more prevalent than other sevenths (in spite of the dissonance of the tritone interval) in mainstream tonal music.

This tonal fusion effect is also used in synthesizers and orchestral arrangements; for instance, in Ravel's Bolero #5 the parallel parts of flutes, horn and celesta resemble the sound of an electric organ.

[31] To interfere, partials must lie within a critical bandwidth, which is a measure of the ear's ability to separate different frequencies.

Any composition (or improvisation) which remains consistent and 'regular' throughout is, for me, equivalent to watching a movie with only 'good guys' in it, or eating cottage cheese.