Harry Potter

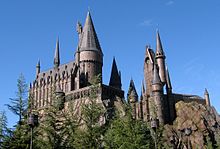

The novels chronicle the lives of a young wizard, Harry Potter, and his friends, Hermione Granger and Ron Weasley, all of whom are students at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry.

Harry encounters the school's headmaster, Albus Dumbledore; the potions professor, Severus Snape, who displays a dislike for him; and the Defence Against the Dark Arts teacher, Quirinus Quirrell.

The first book concludes with Harry's confrontation with Voldemort, who, in his quest to regain a body, yearns to possess the Philosopher's Stone, a substance that bestows everlasting life.

On Voldemort's behalf, Ginny opened the chamber and unleashed the basilisk, an ancient monster that kills or petrifies those who make direct or indirect eye contact, respectively.

Upon returning to Hogwarts, it is revealed that a Death Eater, Barty Crouch, Jr, in disguise as the new Defence Against the Dark Arts professor, Alastor "Mad-Eye" Moody, engineered Harry's entry into the tournament, secretly helped him, and had him teleported to Voldemort.

The series can be considered part of the British children's boarding school genre, which includes Rudyard Kipling's Stalky & Co., Enid Blyton's Malory Towers, St. Clare's and the Naughtiest Girl series, and Frank Richards's Billy Bunter novels: the Harry Potter books are predominantly set in Hogwarts, a fictional British boarding school for wizards, where the curriculum includes the use of magic.

[13] Paintings move and talk; books bite readers; letters shout messages; and maps show live journeys, making the wizarding world both exotic and familiar.

[24] Many of the motifs of the Potter stories, such as the hero's quest invoking objects that confer invisibility, magical animals and trees, a forest full of danger and the recognition of a character based upon scars, are drawn from medieval French Arthurian romances.

[29][30][31] Rowling also exhibits Christian values in developing Albus Dumbledore as a God-like character, the divine, trusted leader of the series, guiding the long-suffering hero along his quest.

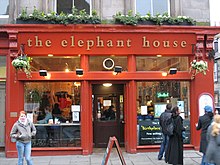

I simply sat and thought, for four (delayed train) hours, and all the details bubbled up in my brain, and this scrawny, black-haired, bespectacled boy who did not know he was a wizard became more and more real to me.Rowling completed Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone in 1995 and the manuscript was sent off to several prospective agents.

The books have seen translations to diverse languages such as Korean, Armenian, Ukrainian, Arabic, Urdu, Hindi, Bengali, Bulgarian, Welsh, Afrikaans, Albanian, Latvian, Vietnamese and Hawaiian.

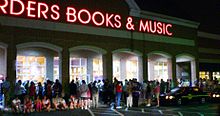

[102] Fans of the series were so eager for the latest instalment that bookstores around the world began holding events to coincide with the midnight release of the books, beginning with the 2000 publication of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire.

On publication, the first book, Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone, attracted attention from the Scottish newspapers, such as The Scotsman, which said it had "all the makings of a classic",[108] and The Glasgow Herald, which called it "Magic stuff".

His overall view of the series was negative—"the Potter saga was essentially patronising, conservative, highly derivative, dispiritingly nostalgic for a bygone Britain", and he speaks of "a pedestrian, ungrammatical prose style".

[112] Ursula K. Le Guin said, "I have no great opinion of it [...] it seemed a lively kid's fantasy crossed with a 'school novel,' good fare for its age group, but stylistically ordinary, imaginatively derivative, and ethically rather mean-spirited.

[120] Jenny Sawyer wrote in The Christian Science Monitor on 25 July 2007 that Harry Potter neither faces a "moral struggle" nor undergoes any ethical growth and is thus "no guide in circumstances in which right and wrong are anything less than black and white".

[122] In an 8 November 2002, Slate article, Chris Suellentrop likened Potter to a "trust-fund kid whose success at school is largely attributable to the gifts his friends and relatives lavish upon him".

[123] In a 12 August 2007 review of Deathly Hallows in The New York Times, however, Christopher Hitchens praised Rowling for "unmooring" her "English school story" from literary precedents "bound up with dreams of wealth and class and snobbery", arguing that she had instead created "a world of youthful democracy and diversity".

Scholars such as Brycchan Carey have praised the books' abolitionist sentiments, viewing Hermione's Society for the Promotion of Elfish Welfare as a model for younger readers' political engagement.

[142][143] Other critics including Farah Mendlesohn find the portrayal of house-elves "most difficult to accept": the elves are denied the right to free themselves and rely on the benevolence of others like Hermione.

[144][145] Pharr terms the house-elves a disharmonious element in the series, writing that Rowling leaves their fate hanging;[146] at the end of Deathly Hallows, the elves remain enslaved and cheerful.

[147] The goblins of the world of Harry Potter have also received criticism for following antisemitic caricatures – particularly for their grotesque "hook-nosed" portrayal in the films, an appearance associated with Jewish stereotypes.

The popularity and high market value of the series has led Rowling, her publishers, and film distributor Warner Bros. to take legal measures to protect their copyright, which have included banning the sale of Harry Potter imitations, targeting the owners of websites over the "Harry Potter" domain name, and suing author Nancy Stouffer to counter her accusations that Rowling had plagiarised her work.

[157][158] The series has landed the American Library Associations' Top 10 Banned Book List in 2001, 2002, 2003, and 2019 with claims it was anti-family, discussed magic and witchcraft, contained actual spells and curses, referenced the occult/Satanism, violence, and had characters who used "nefarious means" to attain goals, as well as conflicts with religious viewpoints.

[174] Older works in the genre, including Diana Wynne Jones's Chrestomanci series and Diane Duane's Young Wizards, were reprinted and rose in popularity; some authors re-established their careers.

[180] Some critics view Harry Potter's rise, along with the concurrent success of Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials, as part of a broader shift in reading tastes: a rejection of literary fiction in favour of plot and adventure.

[181] This is reflected in the BBC's 2003 "Big Read" survey of the UK's favourite books, where Pullman and Rowling ranked at numbers 3 and 5, respectively, with very few British literary classics in the top 10.

[186] Characters and elements from the series have inspired scientific names of several organisms, including the dinosaur Dracorex hogwartsia, the spider Eriovixia gryffindori, the wasp Ampulex dementor, and the crab Harryplax severus.

[215] In 2012, the opening ceremony of the 2012 Summer Olympics in London featured a 100-foot tall rendition of Lord Voldemort in a segment designed to showcase the UK's cultural icons.

[220] Rowling demanded the principal cast be kept strictly British and Irish, nonetheless allowing for the inclusion or French and Eastern European actors where characters from the book are specified as such.