The Hobbit

Bilbo gains a new level of maturity, competence, and wisdom by accepting the disreputable, romantic, fey, and adventurous sides of his nature and applying his wits and common sense.

The author's scholarly knowledge of Germanic philology and interest in mythology and fairy tales are often noted as influences, but more recent fiction including adventure stories and the works of William Morris also played a part.

Bilbo Baggins, the protagonist, is a respectable, reserved and well-to-do hobbit—a race resembling short humans with furry, leathery feet who live in underground houses and are mainly farmers and gardeners.

The plot involves a host of other characters of varying importance, such as the twelve other dwarves of the company; two types of elves: both puckish and more serious warrior types;[8] Men; man-eating trolls; boulder-throwing giants; evil cave-dwelling goblins; forest-dwelling giant spiders who can speak; immense and heroic eagles who also speak; evil wolves, or Wargs, who are allied with the goblins; Elrond the sage; Gollum, a strange creature inhabiting an underground lake; Beorn, a man who can assume bear form; and Bard the Bowman, a grim but honourable archer of Lake-town.

[7][9] Gandalf tricks Bilbo Baggins into hosting a party for Thorin Oakenshield and his band of twelve dwarves (Dwalin, Balin, Kili, Fili, Dori, Nori, Ori, Oin, Gloin, Bifur, Bofur, and Bombur), who go over their plans to reclaim their ancient home, Lonely Mountain, and its vast treasure from the dragon Smaug.

The dwarves, men and elves band together, but only with the timely arrival of the eagles and Beorn, who fights in his bear form and kills the goblin general, do they win the climactic Battle of Five Armies.

Bilbo accepts only a small portion of his share of the treasure, having no want or need for more, but still returns home a very wealthy hobbit roughly a year and a month after he first left.

[26] The additional illustrations proved so appealing that George Allen & Unwin adopted the colour plates as well for their second printing, with exception of Bilbo Woke Up with the Early Sun in His Eyes.

Many fairy tale motifs, such as the repetition of similar events seen in the dwarves' arrival at Bilbo's and Beorn's homes, and folklore themes, such as trolls turning to stone, are to be found in the story.

[47] Tolkien's prose is unpretentious and straightforward, taking as given the existence of his imaginary world and describing its details in a matter-of-fact way, while often introducing the new and fantastic in an almost casual manner.

This down-to-earth style, also found in later fantasy such as Richard Adams' Watership Down and Peter Beagle's The Last Unicorn, accepts readers into the fictional world, rather than cajoling or attempting to convince them of its reality.

[51] The general form—that of a journey into strange lands, told in a light-hearted mood and interspersed with songs—may be following the model of The Icelandic Journals by William Morris, an important literary influence on Tolkien.

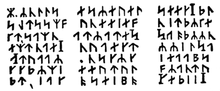

Examples include the names of the dwarves,[54] Fili, Kili, Oin, Gloin, Bifur, Bofur, Bombur, Dori, Nori, Dwalin, Balin, Dain, Nain, and Thorin Oakenshield, along with Gandalf which was a dwarf-name in the Norse.

[67] This progression culminates in Bilbo stealing a cup from the dragon's hoard, rousing him to wrath—an incident directly mirroring Beowulf and an action entirely determined by traditional narrative patterns.

"[70] The scholar of literature James L. Hodge describes the story as picaresque, a genre of fiction in which a hero relies on his wits to survive a series of risky episodes.

She comments, for instance, that the humorous drawings of Morris riding through the wilds of Iceland by his friend the artist Edward Burne-Jones can serve well as models for Bilbo on his adventures.

[72] Tolkien wrote of being impressed as a boy by Samuel Rutherford Crockett's historical novel The Black Douglas and of basing the Necromancer—Sauron—on its villain, Gilles de Retz.

[81] The Jungian concept of individuation is also reflected through this theme of growing maturity and capability, with the author contrasting Bilbo's personal growth against the arrested development of the dwarves.

[83] The analogue of the "underworld" and the hero returning from it with a boon (such as the ring, or Elvish blades) that benefits his society is seen to fit the mythic archetypes regarding initiation and male coming-of-age as described by Joseph Campbell.

[84] Shippey comments that Bilbo is nothing like a king, and that Chance's talk of "types" just muddies the waters, though he agrees with her that there are "self-images of Tolkien" throughout his fiction; and she is right, too, in seeing Middle-earth as a balance between creativity and scholarship, "Germanic past and Christian present".

[86] Whilst greed is a recurring theme in the novel, with many of the episodes stemming from one or more of the characters' simple desire for food (be it trolls eating dwarves or dwarves eating Wood-elf fare) or a desire for beautiful objects, such as gold and jewels,[87] it is only by the Arkenstone's influence upon Thorin that greed, and its attendant vices "coveting" and "malignancy", come fully to the fore in the story and provide the moral crux of the tale.

This idea of a superficial contrast between characters' individual linguistic style, tone and sphere of interest, leading to an understanding of the deeper unity between the ancient and modern, is a recurring theme in The Hobbit.

[92] Smaug the dragon with his golden hoard may be seen as an example of the traditional relationship between evil and metallurgy as collated in the depiction of Pandæmonium with its "Belched fire and rolling smoke" in John Milton's Paradise Lost.

As Janet Brennan Croft notes, Tolkien's literary reaction to war at this time differed from most post-war writers by eschewing irony as a method for distancing events and instead using mythology to mediate his experiences.

C. S. Lewis, friend of Tolkien (and later author of The Chronicles of Narnia between 1949 and 1954), writing in The Times reports: The truth is that in this book a number of good things, never before united, have come together: a fund of humour, an understanding of children, and a happy fusion of the scholar's with the poet's grasp of mythology...

"Lewis compares the book to Alice in Wonderland in that both children and adults may find different things to enjoy in it, and places it alongside Flatland, Phantastes, and The Wind in the Willows.

[114] Tolkien sent this revised version of the chapter "Riddles in the Dark" to Unwin as an example of the kinds of changes needed to bring the book into conformity with The Lord of the Rings,[115] but he heard nothing back for years.

[119] After an unauthorized paperback edition of The Lord of the Rings appeared from Ace Books in 1965, Houghton Mifflin and Ballantine asked Tolkien to refresh the text of The Hobbit to renew the US copyright.

[127] With The History of The Hobbit, published in two parts in 2007, John D. Rateliff provides the full text of the earliest and intermediary drafts of the book, alongside commentary that shows relationships to Tolkien's scholarly and creative works, both contemporary and later.

The plots share the same basic structure in the same sequence: the stories are both quests starting at Bag End, the home of Bilbo Baggins; Bilbo hosts a party that sets the novel's main plot into motion; Gandalf sends the protagonist into a quest eastward; Elrond offers a haven and advice; the adventurers escape dangerous creatures underground (Goblin Town/Moria); they engage another group of elves (Mirkwood/Lothlórien); they traverse a desolate region (Desolation of Smaug/the Dead Marshes); they are received and nourished by a small settlement of men (Esgaroth/Ithilien); they fight in a massive battle (The Battle of Five Armies/Battle of Pelennor Fields); their journey climaxes within an infamous mountain peak (Lonely Mountain/Mount Doom); a descendant of kings is restored to his ancestral throne (Bard/Aragorn); and the questing party returns home to find it in a deteriorated condition (having possessions auctioned off/the Scouring of the Shire).